This story first appeared on Vector, a blog of Boston Children’s Hospital.

“It’s a brutal disease; there’s just no other way to describe DIPG,” says Steve Czech. “And what’s crazy is that there aren’t many treatment options because it’s such a rare, orphan disease.”

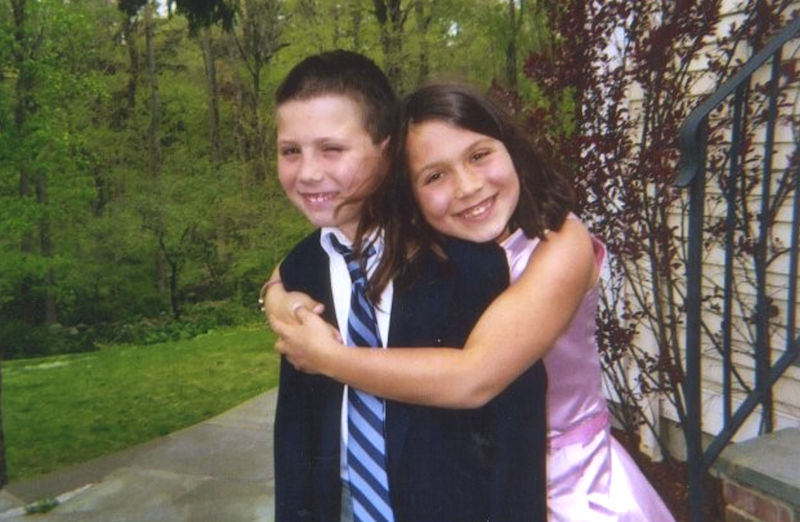

Czech’s son, Mikey, was diagnosed with a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) on Jan. 6, 2008. It was Mikey’s 11th birthday. The fast growing and difficult-to-treat brainstem tumors are diagnosed in approximately 300 children in the U.S. each year.

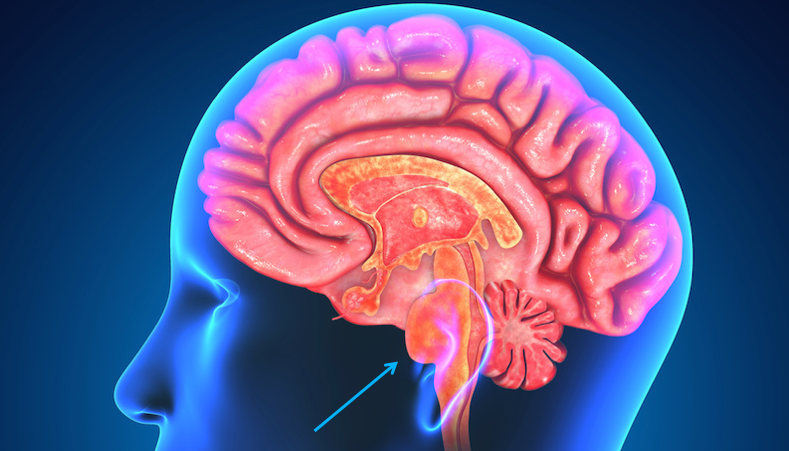

Sadly, the virtually incurable disease comes with a poor prognosis for most children. The location of DIPG tumors in the brainstem — which controls many of the body’s involuntary functions, such as breathing — has posed a huge challenge to successful treatment thus far.

“Typically, they give kids about nine months,” says Czech. “Our lives changed forever the day that Mikey was diagnosed.”

Czech and his wife, Jennifer, brought Mikey from expert to expert and were honest with Mikey and his big sister, Sydney, about his brain tumor.

“Everybody knew everything,” says Czech. “There were no secrets about what was happening.”

Despite treatment through a clinical trial, almost nine months later to the day, the Czech family lost their “happy, athletic, intelligent, caring, perpetually optimistic” Mikey. They were devastated.

Putting the gears of change in motion

After Mikey passed away, the family remained deeply disturbed that the treatment options for their son’s tumor had been nearly nonexistent. With so few kids facing a DIPG diagnosis, DIPG research receives little funding. That stark reality is what spurred the Czechs to take matters into their own hands.

“To stop this from happening to other families, we formed The Mikey Czech Foundation,” says Czech. “We need to develop better treatment options for these kids.”

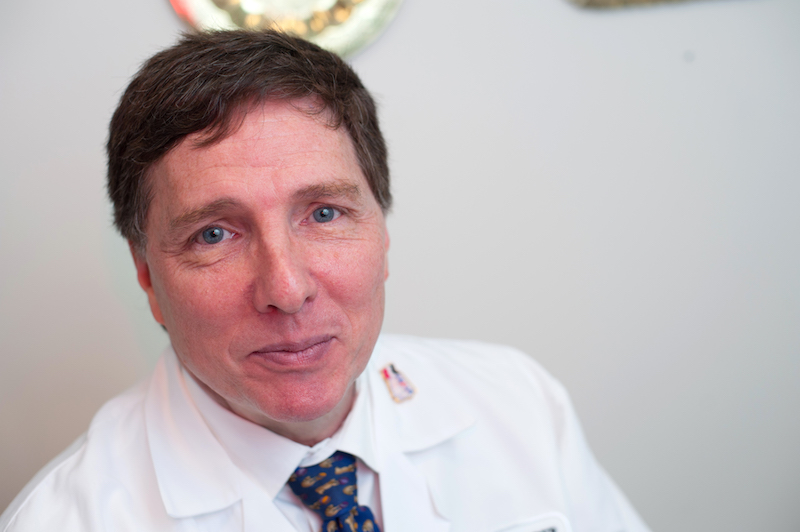

Since 2008, the foundation has been supporting DIPG research and raising awareness. In 2013, the foundation gave a $500,000 grant to Mark Kieran, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Kieran has been developing an aggressive protocol to personalize and improve treatment of DIPGs.

Czech described the grant as “the first in a series of gifts….designed to eradicate this heinous disease.” Most recently, in March 2017, the foundation gave Kieran a second grant of $1 million to further support his DIPG research.

“We think that for the first time, we have the opportunity to change how these tumors respond to treatment,” says Kieran, who is director of the Brain Tumor Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s.

Bridging the gap to DIPG biopsy

For many years, the location of DIPGs — in the brainstem — had made them impossible to be safely biopsied. But since 2002, Kieran has been pushing to establish a new standard of care when it comes to DIPG treatment: the ability to safely genetically sequence each child’s unique tumor at the time of diagnosis.

To make this possible, Kieran’s team, in collaboration with the Broad Institute, developed a safe microbiopsy technique that is capable of retrieving tiny DIPG samples that are only the width of a human hair. From those samples, a tumor’s individual genomic profile could one day be matched with a personalized treatment plan.

“Our Biology and Treatment Study (BATS) clinical trial to biopsy DIPGs was finally approved by the FDA eight years after we had first proposed it,” says Kieran.

Unfortunately, that was more than two years after Kieran had seen Mikey. The Czechs had traveled to Boston for a second opinion shortly after Mikey’s tumor was diagnosed by a medical center in New York. Since the BATS trial was not yet approved, Kieran could not offer a more innovative therapy than would be available to Mikey at a hospital closer to the family’s home in New Canaan, Connecticut.

“Back then, when we couldn’t be any more aggressive in treating DIPG here than at another medical center, it was one of those circumstances where we thought it would be better for Mikey to be treated close to home,” says Kieran.

“Dr. Kieran’s research was the most proactive in terms of what needed to be done — we liked his attitude,” says Czech. “After Mikey passed away, we wanted to identify and support the best DIPG researcher and institution with the most holistic plan to attack these tumors — that was Dr. Kieran’s program.”

The dawn of hope for DIPG

With this support, the trajectory for DIPG research is finally moving upward. The second iteration of the BATS trial is being organized and Kieran hopes it will be underway later this year.

“As soon as we did the first set of BATS biopsies, we saw that there are very specific mutations that require targeting,” says Kieran. “The goal of the new trial will be to base treatment on your child’s specific genomic abnormality.”

This precision medicine approach may finally provide the chance to actually cure DIPGs.

“The Czechs have been critical to us having the resources needed to move this protocol forward,” says Kieran. “Families need to be optimistic that for the first time, we are really able to focus on what’s driving each kid’s individual tumor.”