What is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)?

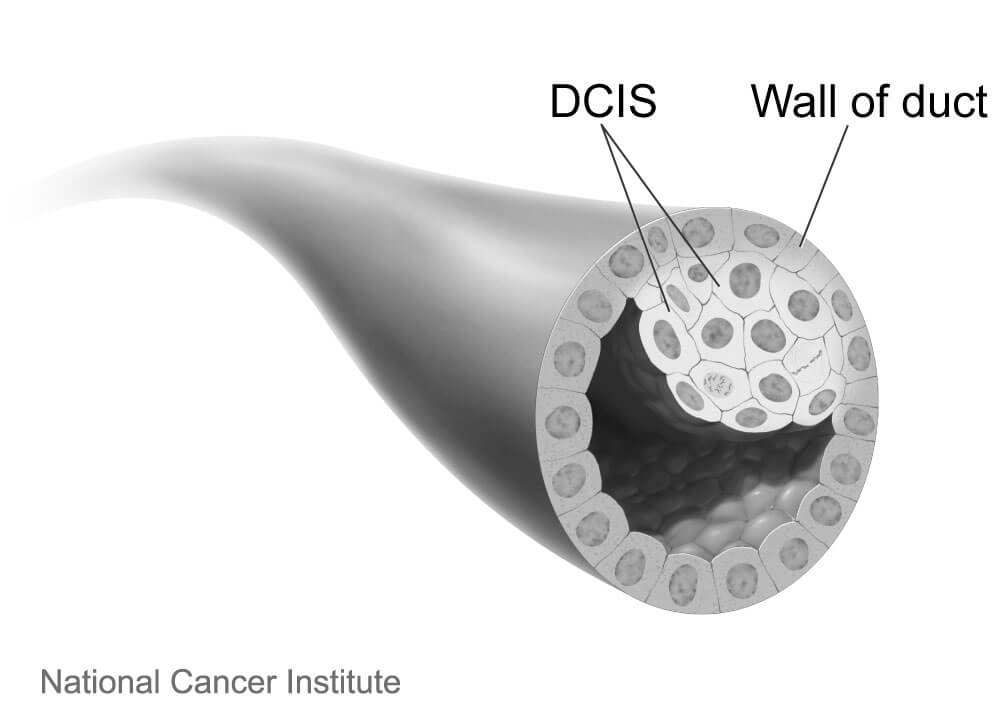

Ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS, refers to a type of breast cancer in which the abnormal cells are confined harmlessly within the milk ducts of the breast. Largely due to wide use of mammography screening, about one in five women diagnosed with breast cancer today have this earliest, highly treatable form of the disease.

Is DCIS technically cancer?

Whether DCIS should even be called cancer has been debated, some arguing that the term creates unwarranted anxiety, because it is harmless as long as it remains confined to the milk duct. DCIS cells “are true cancer cells” but the diagnosis should not paralyze people with fear. It is officially termed stage 0 breast cancer.

What are the symptoms of DCIS?

The condition usually doesn’t cause symptoms. A small number of people may have a lump in the breast or discharge (fluid) coming out of the nipple.

How is DCIS diagnosed?

A mammogram can reveal signs of what might be DCIS, and the diagnosis is confirmed by a needle biopsy.

[Learn more about when to get a mammogram.]

What are the treatment options for DCIS?

DCIS is not a life-threatening condition, and no urgent decision about treatment is necessary. It does have the possibility of turning into an invasive cancer, so a person diagnosed with DCIS needs to have a conversation with their physician about what next steps to take.

Once needed, the primary treatment for DCIS is surgery, either a breast-conserving lumpectomy or a mastectomy to remove the lesion and part or all of the breast. Lumpectomy is often supplemented with radiation therapy, and in some cases endocrine (hormone-blocking) therapy is added to forestall a recurrence. Currently, patients treated for DCIS have excellent breast-cancer-specific survival of about 98 percent after 10 years of follow-up and can expect normal longevity.

Examining cells from a biopsy can help pathologists determine if the DCIS is considered low, medium, or high-risk of becoming invasive cancer. There are widespread concerns that many people with low-risk DCIS that is unlikely to become invasive are being overtreated, incurring needless surgeries and potentially long-lasting pain and emotional distress. Whether a person with low-risk DCIS should undergo immediate surgery or could safely delay treatment and be monitored with regular mammograms is an issue being studied in a clinical trial called COMET (Comparing an Operation to Monitoring, with or without Endocrine Therapy). It is the first large-scale comparison of these two approaches for low-risk DCIS.

Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, is the co-principal investigator of COMET, which began in early 2017 and is enrolling 1,200 women age 40 or older who have been newly diagnosed with low-risk DCIS at cancer centers across the United States. The women are randomly assigned to one of two groups: One group will undergo standard treatment with surgery with or without radiation, while women in the other group will be closely monitored with mammograms and will be recommended to have surgery only if invasive cancer is detected. Women in both groups will have the option to take hormonal therapy to reduce risks further.

Expected to be completed in 2023, the COMET study will compare the cancer and quality of life outcomes in the two groups. The results will help doctors and patients determine if women with low-risk DCIS can safely choose to avoid immediate aggressive treatments and rely on active monitoring to watch for signs that the DCIS is becoming invasive.

What happens if DCIS is not treated?

Left untreated, some of these lesions will in time escape through the wall of the ducts, becoming invasive, and then potentially enter the lymph nodes or blood stream, where they can spread to other parts of the body. Other DCIS lesions will never become invasive in the woman’s lifetime. Because the course of DCIS is unpredictable, it is almost always treated to forestall the development of a more risky invasive tumor.

Comments are closed.