By Erin Cummings

As a 44-year survivor of childhood cancer, I never would have imagined that patients could be treated in a place as warm and inviting as Dana-Farber. Each time I come for follow-up care, or as a member of the Art and Environment Committee that helps select artwork for the Institute, I think about what a long, long way we have come in treating cancer — and the whole patient – since 1972.

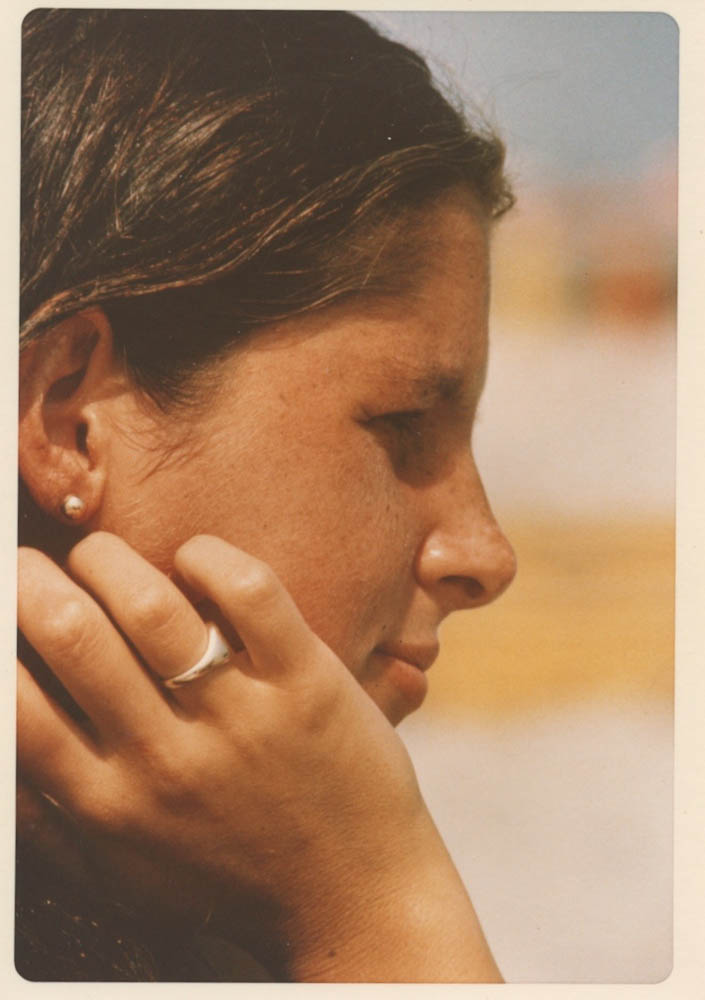

That was the year I turned 15 and started my sophomore year of high school, just outside New York City. It was also when I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, now known as Hodgkin lymphoma. Art was already an important part of my life then. My dad was the principal at my school, and also a very good painter. The two of us would go around together all the time; he’d paint and I would sketch.

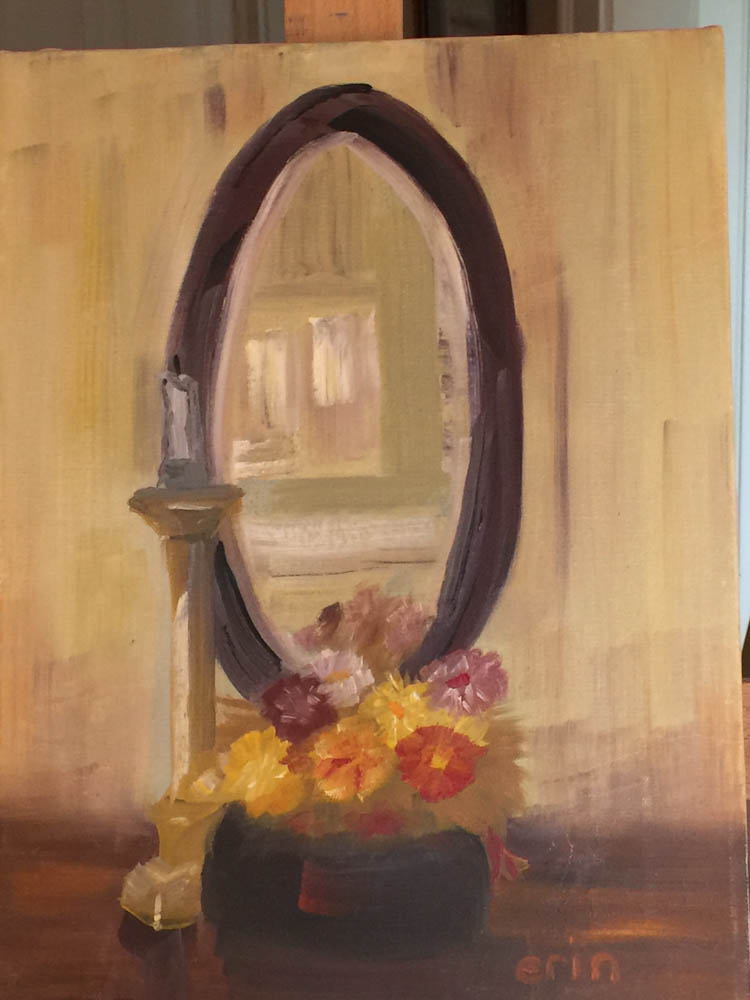

The weekend before I started treatment, we went down to the Jersey Shore and he had me sketch a still life – a mirror with a bowl and candlesticks. He was trying to get me to think about something other than cancer, and to see that I was still me under that new diagnosis: the same cheerleader, the same artist, the same kid. Cancer wasn’t going to take that away from me.

The walls of the pediatric ward at my local hospital where I stayed that summer were an institutional pistachio-green color. I had my chemotherapy in the emergency ward, on a stretcher – or sometimes in the hallway if they were really busy. There was no TV, music, or books, no anti-nausea medications, and no one to keep me company like another teenager or a social worker. Unless you count the murals of cartoon characters in the hall, there was no art either. It was a cold, lonely experience.

Read more:

My chemotherapy treatment ended just before my high school graduation in 1975, and even though I went on to become a social worker, I never stopped loving art. In the 1990s I launched a side business painting murals – starting with the pediatrician’s office where my four kids went. I painted images of the Boston Public Garden and the area around the Common for their waiting area. I also did all their examining rooms; I painted one with Disney characters, another with a huge map of the United States, and one with windsurfers for the teenagers.

The irony was not lost on me; I was creating art for sick kids and giving them something to look at that was better than what I had back in my hospital in 1972.

About five years ago, after having open-heart surgery related to my cancer treatment, I started going to the Perini Family Survivors’ Center at Dana-Farber. My friend Jane Mayer chaired the Art and Environment Committee, and said they were looking for survivors to lend perspective to the group. I felt like Dana-Farber was becoming my new home, and learning about the committee was a revelation for me.

It’s a great group of people – doctors, nurses, engineers, architects, trustees, survivors, and members of the Friends of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which oversees the committee. We meet at Dana-Farber once a month to go over paintings, sculptures, mobiles, and other works being considered for inclusion; hear from artists who want their work exhibited; and scope out different areas on campus where pieces might go. We all have our own perspective on what’s best for patients, and it is fascinating what the art brings out in different people.

Things certainly have come a long, long way since 1972. No patient should feel like I did then. When I get off those elevators in the Yawkey Center for Cancer Care at Dana-Farber, and see a favorite painting of ballet dancers, I’m a long way from that ugly green corridor.

Thank you Erin for the amazing person you are, a true inspiration and hero in my life!