Depending on your type of cancer, your care team can include many providers, including five or more physicians. They each play a distinct but equally vital role — some of it face-to-face with you; some of it behind the scenes. These physicians apply their respective training and experience and work together to evaluate and coordinate the best cancer care for you.

Medical Oncologist

The medical oncologist, who can consider all of the patient’s possible options, functions as the quarterback of the cancer care team, according to Douglas Rubinson, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“When a patient has complicated care—requiring chemotherapy, radiation, surgery and perhaps other interventions—the medical oncologist is the one coordinating all of those different disciplines,” Rubinson says.

In addition, one of the primary jobs of a medical oncologist is to administer chemotherapy or immunotherapy for the systemic treatment of the patient’s cancer. The oncologist works with patients to decide their appropriate treatment – whether that’s intravenous (IV) or oral medication, chemotherapy or immunotherapy, or some combination of treatments. They also gauge whether a patient’s other medical issues might affect a potential line of treatment and what side effects and risks go along with that treatment.

“Once a patient is on chemotherapy, we get a sense of how well it is being tolerated and how effective it is,” Rubinson says. “We make sure it’s not causing any untoward toxicity that needs to be managed. We use that information, along with data on the patient’s tumor and genetic testing, to decide if we should continue with that therapy or make a change.”

Surgical Oncologist

A surgical oncologist is a surgeon who specializes in the surgical removal of cancerous tumors from the body.

“A tumor might be removed with a goal of curing the cancer or for palliative reasons, to reduce symptoms caused by that tumor,” Rubinson says. “The decision is not only whether a tumor can be removed, but whether it can be removed safely.”

The surgical oncologist evaluates whether a patient’s existing medical issues would create too great of risk for surgery to proceed. After surgery, they follow up to make sure no post-op complications arise.

Radiation Oncologist

When radiation therapy is part of the treatment plan, it’s the radiation oncologist who creates the treatment plan to safely administer radiation therapy.

“Radiation may be used as a definitive treatment to eliminate the site of disease that can’t be surgically removed,” Rubinson explains. “It might also be used to reduce symptoms by treating one site of a patient’s disease. Or after surgery, it can be used to reduce the risk of recurrence around the surgical area.”

Radiation oncologists will consider the effects of radiation not only on the cancer site but on the surrounding systems as well – that’s one reason why their medical school training includes a year of internal medicine residency.

“Radiation oncologists need to formulate the proper dose of radiation necessary to effectively treat the tumor, but spare the surrounding structures as much as possible,” Rubinson says.

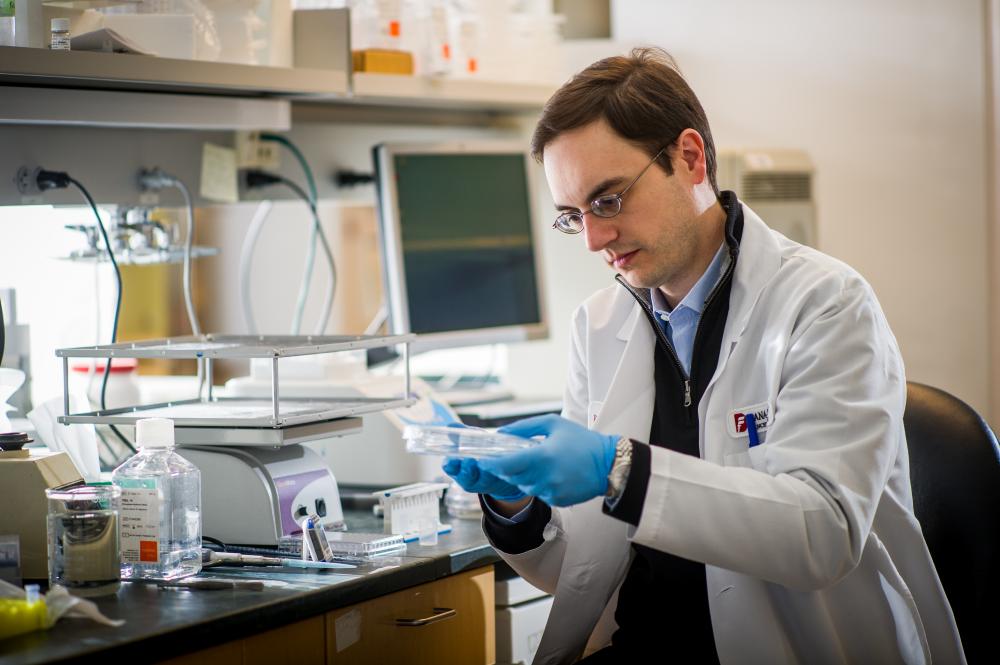

Pathologist

When your biopsy or specimen is sent off to the lab, it arrives at the bench of a pathologist. This physician is trained to identify changes in cells, tissues and organs that result from disease.

“The pathologist is an essential member of the care team,” Rubinson says. “They look at the sample under the microscope and confirm the patient’s diagnosis.”

Some cancers may be easy to accurately diagnose – like making sure that a biopsy from a tumor found during a colonoscopy is a colon cancer. Other times, there may be a lot of uncertainty as to where a cancer started, or an unexpectedly rare pathology may be present. It takes a highly trained eye to be able to recognize its cellular structural changes. The pathologist may employ special staining, DNA sequencing, and other specialized tests to make a diagnosis.

Learn more about cancer care from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.