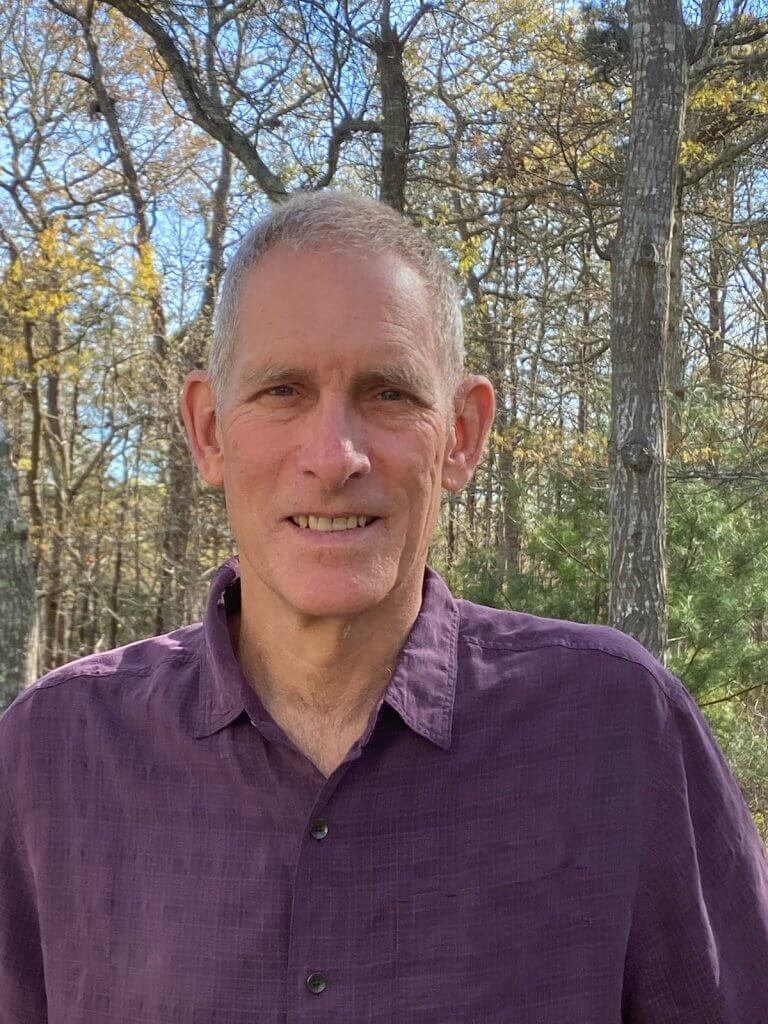

Karl Helfrich, PhD, has been a cyclist for 40 years. When he was diagnosed with a slow-growing brain tumor, he thought that might be the end of his hobby.

Instead, he was only off the bike for three weeks, and continued to ride the roads near his home in Falmouth, Mass. while undergoing radiation and chemotherapy treatment — some of which was part of a clinical trial.

“I felt incredibly fortunate from the start,” said Helfrich, 65, an emeritus scientist of physical oceanography at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where he studies the fluid dynamics of the earth, ocean, and atmosphere.

Treatment, and a trial

Helfrich first noticed something was wrong in January 2021, when he was working at home alongside his son, a Northeastern University student taking classes remotely at the time due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I was trying to work on my research and the world closed in,” he said. “I put my head on my desk. My son was right there and realized something was wrong, then he and my wife took over.”

It turns out Helfrich was having a focal seizure, where the nerve cells in his brain went haywire and sent out a flood of uncontrolled electrical signals. After three days in the hospital undergoing various testing, including an MRI of the brain, doctors found a lesion.

After surgery, a biopsy showed that he had a grade II glioma, a slow-growing brain tumor. He was referred to David Reardon, MD, clinical director of the Center for Neuro-Oncology at Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, who recommended Karl begin a course of daily radiation and daily oral chemotherapy for six continuous weeks, then 12 months of chemotherapy. Dana-Farber worked with another care team at a local hospital near Helfrich so he didn’t need to make the two and a half hour round trip to Boston for each radiation session.

The Institute offered him a clinical trial aimed at investigating the use of ultrasound to improve the uptake of temodar, a chemotherapy drug, for the first six months of his 12-month chemotherapy course. Chemotherapy can be less effective in treating glioblastoma than cancers in other parts of the body because of the blood-brain barrier, a protective layer of cells that stops toxins from entering the brain but also prevents cancer drugs from reaching their intended targets. Early research shows that a non-invasive ultrasound done at the cancer site before taking the drug can open the blood brain barrier, allowing more of the medication in to attack cancer cells.

He was a good candidate for the trial, said Jennifer Stefanik, NP, because of his specific kind of cancer, and he was in good health otherwise with an excellent chance of tolerating possible side effects.

“It’s not that far removed from the kinds of fluid dynamics I study at Woods Hole,” Helfrich said. “I immediately understood the principle of what an ultrasound treatment before taking the temodar is trying to do.” The results from this study have not yet been published.

Stefanik isn’t surprised that Helfrich volunteered to be part of the trial. Clinical trials are scientific studies in which new treatments — drugs, diagnostic procedures, and other therapies — are tested in patients to determine if they are safe and effective. Nearly all cancer drugs in use today were tested and made available to patients through clinical trials.

“He’s a very motivated patient, and invested in his care,” she said. “Of course the trial is hopefully a benefit to him, but he was always willing to do whatever he could for himself and so that his diagnosis could benefit others.”

‘I can do whatever I want’

Helfrich recently retired from his full time position at Woods Hole and transitioned into emeritus status, which means he keeps his office and continues to advise a post-doctoral student there.

While he has aphasia, which can sometimes lead him to say the wrong date or struggle to find the right word, “the shocking thing is that physically I feel fine. I can do whatever I want,” he said, including continuing to cycle five to six days a week, sometimes alone and sometimes with his wife. “It just makes me feel better physically and mentally, and in a weird way I enjoy the exhaustion,” he said.

His aphasia has also improved, he added, helped by time that has allowed his brain to heal, as well as speech therapy.

“When I first started treatment, I didn’t know what to expect. It’s such a big diagnosis,” he said. “But I feel good, and I feel like I’m getting excellent care.”