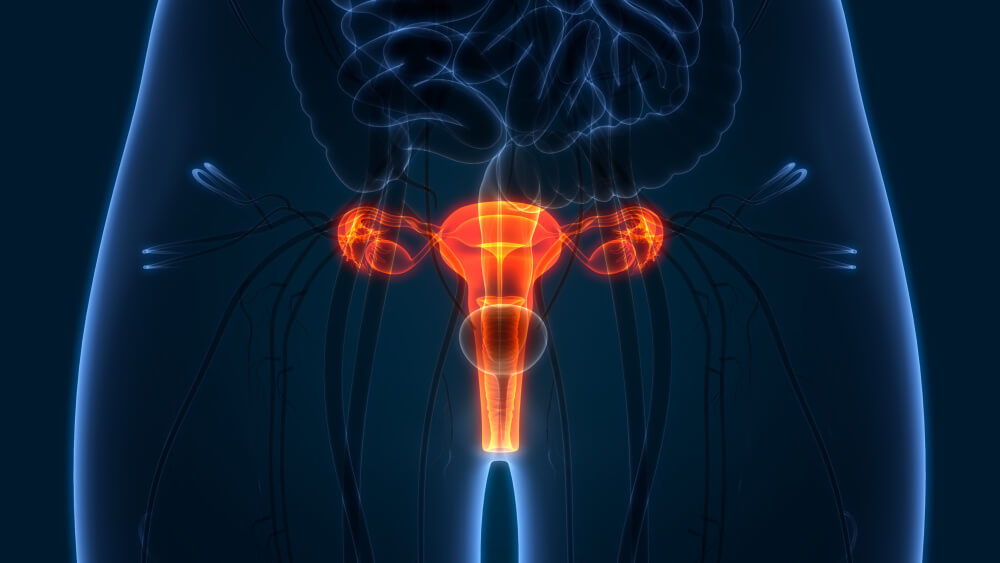

Ovarian cancer almost always starts in the fallopian tubes.

It’s counterintuitive. Why is it called ovarian cancer if it doesn’t start there? For a long time, the ovaries were assumed to be the source because that is where the cancer is concentrated at the time of diagnosis.

But about 20 years ago, researchers took a closer look and discovered that malignancy usually begins in the fallopian tubes.

“We’re used to thinking that ovarian cancer always comes from the ovary,” says Kevin Elias, MD, director of the Gynecologic Oncology Laboratory, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber. “But decades of data shows that is not true.”

The discovery has resulted in a change in clinical practice. Since 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended that doctors and their patients discuss opportunistic salpingectomy — the removal of the fallopian tubes during another procedure, such as a hysterectomy — as a means of preventing ovarian cancer. Women may also elect fallopian tube removal during non-gynecological procedures, such as weight loss surgery or gall bladder surgery.

“We have to educate patients and providers so that they can make the right decisions about ovarian cancer prevention,” says Elias.

What is opportunistic salpingectomy?

Opportunistic salpingectomy is the removal of the fallopian tubes during another planned surgical procedure, such as a hysterectomy, without removing the ovaries. The fallopian tubes could also be removed during general surgery, for instance, to correct a hernia or remove the gall bladder.

Who should consider the procedure?

Women who have an average risk of ovarian cancer who no longer desire fertility but also want to reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer might consider the procedure. Women with an elevated risk due to a gene mutation or family history should speak to their genetic counselor or doctor for more information.

What are the benefits and drawbacks?

For women with an average risk of ovarian cancer, the surgery has the potential to reduce the likelihood of ovarian cancer. The surgery is not reversible and causes infertility. Pregnancy is still possible, though only via in-vitro fertilization. For pre-menopausal women, removal of the fallopian tubes only, and not the ovaries, does not induce menopause.

The recovery time for fallopian tube removal is a few days to a few weeks, though the overall recovery time will depend on the primary reason for surgery.

What evidence supports the idea that removal of the fallopian tubes prevents ovarian cancer?

A 2022 retrospective study in Canada followed nearly 26,000 women over an average of seven years after having their fallopian tubes removed during hysterectomy. None of the women developed high-grade serous ovarian cancer, an aggressive form of the disease. Rates of ovarian cancer were lower than expected rates, which were based on rates in a control group of individuals who underwent hysterectomy alone or tubal ligation.

How was the connection between fallopian tubes and ovarian cancer discovered?

Women with an inherited elevated risk of ovarian cancer started opting to remove both ovaries and fallopian tubes in the 90s as a means of prevention. Around 2000, pathologists started noticing occasional cancers in the removed fallopian tubes.

Christopher Crum, PhD, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and Dana-Farber, developed a dissection protocol to carefully examine the parts of the tubes closest to the ovaries. Using this procedure, termed the SEE-FIM protocol, Crum and others saw a pattern emerge suggesting that ovarian cancers start in the fallopian tubes.

“This not only shifted our attention away from the ovary, but it immediately shifted our attention to preventing the disease with salpingectomy,” explains Crum.

What challenges remain in making this clinical change?

In gynecology, clinicians have rapidly adopted opportunistic salpingectomy in the U.S. Between 2010-15, the percentage of hysterectomies that included salpingectomies increased from 5 to 60%. The potential benefits of the preventive surgery could reach more people, though, so education is needed to raise awareness of the potential for prevention.

“It’s important to educate doctors, but we also want to educate patients and empower them to start this conversation with their physicians,” says Elias.

About the Medical Reviewer

Dr. Elias is a gynecologic oncologist and surgeon-scientist at Dana-Farber and Brigham and Women's Hospital. He treats women with all types of gynecologic cancer. His areas of expertise are gestational trophoblastic disease, familial cancer syndromes, and ovarian cancer.