A stem cell transplant is one of the most powerful tools doctors have for treating certain kinds of cancers and blood-related diseases. The “grafted” cells involved in a transplant are known as hematopoietic stem cells, meaning they’re able to develop into all types of blood cells — red blood cells, which deliver oxygen throughout the body; white blood cells, which fight infections and other diseases; and platelets needed for clotting.

Transplant basics

In all transplants, patients are treated with chemotherapy, followed by an infusion of a blood-forming stem cell graft from a suitable donor. The donor can be a separate individual (an allogeneic transplant) or the patient themself (an autologous transplant). The infused stem cells migrate to the interior of the bones, where they build new bone marrow that produces red and white blood cells and platelets.

The major types of stem cell transplant are:

Autologous transplant

Patients undergoing an autologous transplant first receive high doses of chemotherapy, which destroys tumor cells in the bone marrow, the spongy tissue inside the bones where blood cells are made. They then receive an infusion of their own (autologous) stem cells, which were collected prior to the chemotherapy. Because the infused cells are the patient’s own, they do not trigger immune reactions.

Allogeneic transplant

As in an autologous transplant, patients are first treated with chemotherapy. They’re next infused with stem cells from a compatible but non-DNA identical donor. The stem cells settle into the bones and generate new blood cells. Because the infused cells are not the patient’s own, they can trigger an immune reaction.

What are the types of immune reactions that can occur after a stem cell transplant?

Two kinds of immune reaction can occur after a donor stem cell transplant:

Failure to engraft

This occurs when the donor stem cells fail to take hold in the patient’s bone marrow and generate blood cells. The most common treatment for failure to engraft is another transplant, possibly with stem cells from a different donor after re-treating the patient with additional chemotherapy. Other options may include an infusion of white blood cells from the donor or new approaches being tested in clinical trials.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

This occurs when stem cells transplanted from a donor produce immune system cells that attack the recipient’s tissues and organs. With one of the largest and most experienced transplant programs in the country, Dana-Farber physicians and nurses are skilled in helping patients manage GVHD when it occurs.

What determines whether a transplant donor and recipient are compatible?

Most of our cells have surface proteins called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), which tell the immune system whether a cell belongs in our body (self). If it does belong, it will be left alone (providing it isn’t infected or otherwise diseased). If it’s found to be foreign to the body (non-self), it will be attacked and destroyed by the immune system.

The more closely a transplant patient’s HLA markers match those of the donor, the more likely the donor cells will engraft and the lower the risk of GVHD. Doctors generally seek to match patients with donors who share at least eight HLA markers. For transplants involving a half-matched (or haploidentical) donor, a match of four to eight HLA markers may be sufficient.

What happens when donor stem cells launch an immune reaction?

There are two forms of the disease: acute and chronic.

- Acute GVHD primarily affects the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. The symptoms can include rash, yellowing of the skin and/or eyes, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or other gastrointestinal problem.

- Chronic GHVD symptoms can include rash, shortness of breath, difficulty swallowing, weight loss, fatigue, vaginal dryness, tightness of the joints.

In either category, the extent of GVHD on the body can vary: it can be mild, moderate, or, in some cases, very severe.

What can be done to reduce the risk of GVHD or minimize its effects?

A variety of treatments are used to treat chronic and acute GVHD. Treatment is often geared to the tissue or organ affected by the disease. Many patients are successfully treated with corticosteroid medicines to help suppress the immune system, dampening its attack on the body. Newer immune suppressive agents are constantly being evaluated, and several have recently been approved for acute and chronic GVHD.

Is research being done to better treat GVHD?

GVHD prevention is a major area of research. Typical immune suppressive medications (such as tacrolimus and methotrexate) have been used for decades to reduce GVHD risk. In the past decade use of post-transplant cyclophosphamide as a GVHD prevention treatment has gained popularity and has recently been shown to outperform the prior standard of care. Other novel approaches involve the use of biologic agents like abatacept.

A variety of new approaches to preventing and treating both acute and chronic GVHD are currently being studied in clinical trials and developed in laboratory research.

One example is the ROCKstar study led by Dana-Farber’s Corey Cutler, MD, MPH, which found that the drug belumosudil is effective at alleviating symptoms in patients with chronic GVHD that is resistant to prior steroid therapy. It is now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

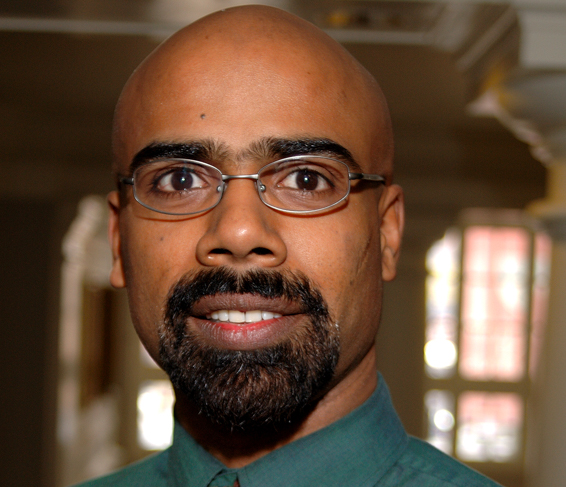

For patients with a severe form of acute GVHD, a clinical trial led by Dana-Farber’s John Koreth, MBBS, DPhil, offers promise. Koreth and colleagues found that an upfront combination of the drug itolizumab and steroid therapy produced substantial improvements in most of the acute GVHD patients participating in the trial. A pivotal phase III trial of this approach is now under way.

About the Medical Reviewer

Dr. Koreth received his MD from the University of Delhi, India, in 1993. After receiving his PhD from Oxford University, he completed his postgraduate training at Brigham & Women's Hospital, followed by fellowships in Hematology/Oncology at DFCI, BWH, and MGH. In 2004, he joined DFCI, and is currently a member of the Hematologic Malignancies staff.