Immunotherapy refers to treatments that use the body’s own immune system to combat cancer. Radioimmunotherapy (RIT), specifically, is a combination of radiation therapy and immunotherapy.

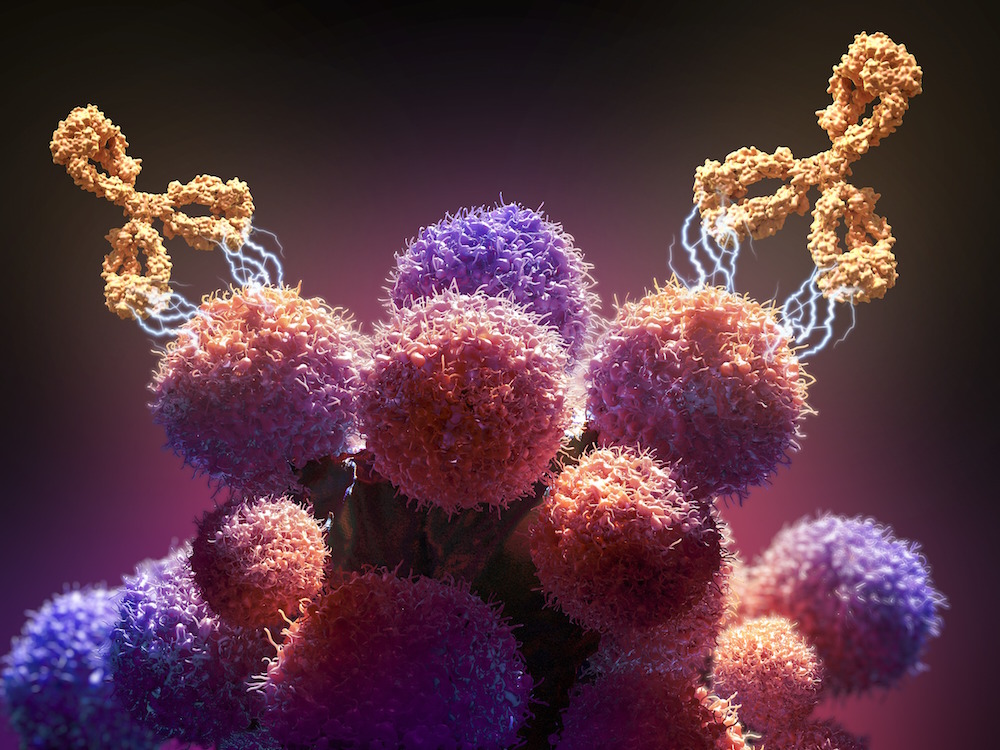

Many forms of immunotherapy employ monoclonal antibodies, which are designed to target certain antigens – foreign substances in the body – that live on the surface of cancer cells. They latch onto cancer cells and act as a “call to arms” for other disease-fighting soldiers in the immune system.

Monoclonal antibodies are most commonly used on their own to treat cancer; these are called “naked mAbs.” Others, called conjugated monoclonal antibodies, are paired with a radioactive substance and injected into the bloodstream. In the case of radioimmunotherapy, they can travel and bind to cancer cells and deliver high doses of radiation directly to tumor cells. These conjugated monoclonal antibodies target the antigen directly, an approach that inflicts less damage to the normal cells in other parts of the body than naked mAbs.

In this case of treating non-Hodgkin lymphoma, radiolabeled antibodies called ibritumomab tiuxetan latch onto the CD20 antigen found in lymphocytes, otherwise known as B cells. Lymphoma begins in the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, and tends to travel throughout the body and land in multiple places, all at the same time.

Researchers are also studying antibody pairings with different radioactive agents and their potential uses in treating prostate cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer, leukemia, high-grade brain glioma, and colorectal cancer.

Compared to months of traditional chemotherapy, RIT is administered in one week through a series of steps. Before treatment can begin, the patient must receive a dose of the monoclonal antibody in an IV injection without the radioactive agent. This initial infusion serves to protect the non-malignant B cells in the body from the radiation that will be used in treatment.

Next, the radioactive material is injected. After about a week, images are taken to determine where the radioactive material has traveled and how long it remains there. This information is used to determine if the patient is a candidate of candidate for RIT. The actual treatment, given seven to nine days after the first scan, contains both the monoclonal antibody and the radioactive agent.

Radioimmunotherapy is rarely used to treat indolent lymphoma because it has not been shown to be superior to the targeted therapy, rituximab, according to Ann LaCasce, MD, MMSc, a medical oncologist specializing in lymphoma and director of the Dana-Farber/Partners CancerCare Hematology-Medical Oncology Fellowship Program. It is also associated with potential damage to stem cells, and it does not have a better side effect profile than chemotherapy.

Learn more about immunotherapy from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.