A traditional biopsy is a test in which a piece of tissue is removed from a patient for analysis in a laboratory. A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope, noting the shape, structure, and internal activity of the cells to determine whether the cells are cancerous and, if so, what type of cancer they represent. Increasingly, the tissue is tested for genetic irregularities known to be associated with cancer.

A liquid biopsy is a non-invasive blood test that can provide researchers and physicians with information about a patient’s cancer. There are two basic types of liquid biopsies: one studies circulating tumor cells and the other studies non-cellular material in the blood, such as DNA. Recently, there has been tremendous progress using the second type of test, where free-floating DNA in the bloodstream is studied. Tumors shed this DNA into the blood as the cells within them die. By collecting and analyzing this DNA, scientists and doctors may be able to get a “snapshot” of the genetic mutations and other irregularities that are driving a tumor’s growth. That information can help doctors determine which therapies have the best chance of working and which are likely to be ineffective.

One of the advantages of a liquid biopsy is that because it requires only a simple blood draw, blood samples can be taken repeatedly over the course of a patient’s treatment. Changes in the quantity or composition of tumor DNA within the blood can indicate how well or poorly a particular therapy is working, and whether a tumor is evolving in ways that might make it drug-resistant, indicating a need for a change in treatment.

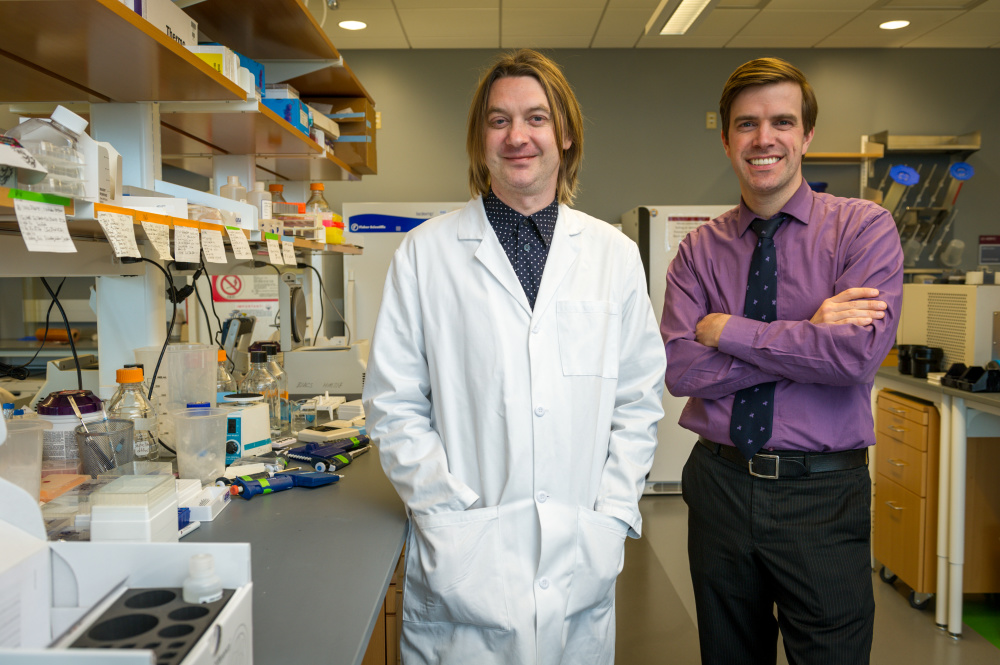

Liquid biopsies are currently conducted primarily for research, to help scientists better understand the basic biology of cancer. Last year, for example, research led by Dana-Farber’s Geoffrey Oxnard, MD, and Cloud Paweletz, PhD, reported the discovery of a new type of drug-resistant mutation that occurs in lung cancer patients after treatment with a new targeted therapy called osimertinib. This mutation, known as EGFR C797S, was first identified in tumor DNA floating in a patient’s blood and was later confirmed by a tumor biopsy.

One of the challenges of liquid biopsies has been ensuring adequate accuracy. In some cases, there is very little tumor DNA present in the blood specimen, making it difficult to detect cancer-related mutations. Currently, conventional tissue biopsies remain the gold standard for determining the genetic makeup of tumors in patients.

As liquid biopsy techniques have been refined and improved in recent years, they’ve begun to approach the accuracy and reliability of tissue biopsies in some cases. A new study led by Oxnard and Paweletz showed that a liquid biopsy approach called rapid plasma genotyping can accurately and quickly detect mutations in two key genes in non-small cell lung cancer tumors, the most common type of lung cancer. The test proved so reliable that Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center has become the first medical facility in the country to offer it to all patients with non-small cell lung cancer, whether at the time of first diagnosis or of relapse following previous treatment.

The test employs a technology known as droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), which was piloted and optimized for clinical use by Paweletz and his colleagues at the Translational Research lab of the Belfer Center for Applied Cancer Science at Dana-Farber.

“This advance was accomplished with a high degree of collaboration between scientists working in the laboratory, physician-researchers in the clinic, and pathologists,” says Oxnard. “This kind of joint effort is critical for using basic science insights to benefit patients.”

Learn more about Oxnard’s liquid biopsy research in the video below: