In early 2015, Kim Delling had put her 2009 bout with breast cancer behind her. Then, at a routine checkup, her doctor ordered an additional test. “I knew something was up,” recalls Delling, a 50-year-old real estate agent in Wilmington, Mass.

The cancer had come back. It had spread to her lungs, liver, and lymph nodes and was, according to her local doctor, incurable.

A visit with Erica Mayer, MD, MPH, a breast oncologist at the Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers at Dana-Farber, softened the news. “Dr. Mayer said she had a toolbox full of tools for me,” says Delling. “Just because this disease is incurable doesn’t mean I can’t live with it.”

That shift in perspective – looking at metastatic breast cancer as a chronic disease rather than an immediate near-term death sentence – is the result of a transformation in the way doctors treat it. New medicines and improvements in supportive care are making it possible for many patients to live with the disease for many years, and live relatively well.

Approximately 250,000 women and 2,000 men are diagnosed with breast cancer in the U.S. each year according to the National Cancer Institute. In about six percent of those cases, the cancer has already spread to liver, lung, bone, or brain tissue. Metastatic disease, however, also occurs in those who were treated for early stage disease, like Delling. Researchers estimate that 20 to 25 percent of patients with early breast cancer will develop metastatic cancer eventually, despite advances in early-stage care.

For patients with metastatic disease, currently numbering about 200,000 in the U.S., the disease is not curable. But individual experiences vary widely. While the disease can occasionally move rapidly, more patients are living longer than ever before. About 26 percent of women with metastatic breast cancer are still living five years after diagnosis and some continue to do well 10 or 15 years after diagnosis.

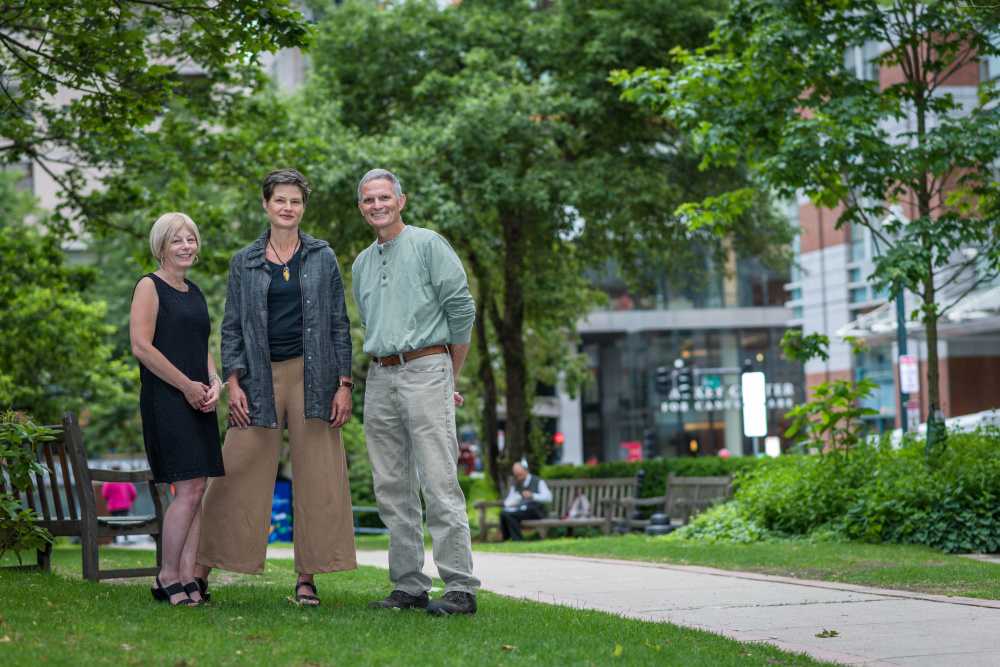

“We’ve taken steps forward, and for certain types of metastatic breast cancer, large steps forward, so more patients are living longer than ever before,” says Eric P. Winer, MD, director of Breast Oncology and chief strategy officer for Dana-Farber. “But it is still a disease women ultimately die from, so these steps make it so more women can live a long time with the disease and be, essentially, symptom free.”

Drivers of Change

Targeted therapies that block the molecular drivers of cancer growth have helped extend life expectancy for metastatic breast cancer patients. For instance, Herceptin, which is used to treat women with HER2-positive breast cancer, frequently extends survival for women with metastatic disease. In the past few years, even more potent medicines that target HER2 have been approved, adding to the success. “The more we target HER2, the better people with this disease do,” says Nancy Lin, MD, clinical director of Breast Oncology at the Susan F. Smith Center, and director of the Metastatic Breast Cancer Program.

For estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, a similar story may be unfolding. Palbociclib and ribociclib, which target cancer drivers called CDK4 and CDK6, were recently approved for routine use, and a similar drug, abemaciclib, is currently in late-stage trials.

Women with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer have been the hardest to treat. Just five years ago, there were few trials of new drugs for this condition, but that has started to change. Trials are currently testing antibody-drug conjugates, so-called smart bombs that attack the cancer but leave healthy tissue relatively untouched, and immunotherapy drugs, which have shown dramatic success in melanoma and lung cancer, and early promise in breast cancer. “There are a lot of exciting drugs in late stage trials, so there’s more hope than ever before that at least one of them will be a breakthrough,” says Dr. Lin.

“People would never in a million years know that I have stage 4 cancer,” Dellin says.

Currently, Dana-Farber has dozens of open clinical trials testing new drugs and new treatment regimens for all sorts of metastatic breast cancer, including cases in which the cancer has spread to the brain. In the past, few trials were open to patients with brain metastases, but Dana-Farber offers several. “This is no longer the forgotten corner of metastatic breast cancer,” says Dr. Lin.

For Delling, supportive care and her doctor’s thoughtful treatment approaches have kept her active and working for the two years since she learned her cancer was metastatic. Over time, she’s participated in three trials and tried five treatments. Her current regimen, which is not part of a trial, is working extremely well. “People would never in a million years know that I have stage 4 cancer,” she says.

But she does have to live with side effects, such as neuropathy, which causes numbness in her hands and pain in her feet. “At times, it’s like walking on broken glass,” she says.

Delling takes medications to minimize the nerve damage, and her care team at Dana-Farber watches her closely. “It’s another layer of care that helps people feel better and maybe even do better,” says Dr. Lin.

Embracing Care

With so many treatment options and potential side effects, patients need extra support to track and manage their symptoms and care. To provide this support, Lin and colleagues at Dana-Farber launched the EMBRACE (Ending Metastatic Breast Cancer for Everyone) program. “Taking care of metastatic breast cancer patients has become increasingly complicated,” says Dr. Lin. “We wanted to make sure we provide consistent support for our patients.”

EMBRACE started out as a research program to help Dana-Farber clinical researchers learn more about metastatic breast cancer from their patients. Now, it is also a clinical program with outreach, educational programs, and coordinated care. Patient coordinators support oncology teams by knowing what is going on with patients, tracking tumor test results, and identifying potential clinical trials. They also connect patients to the resources available to them, such as support groups, palliative care, and nutritionists.

EMBRACE also remains a research program that has so far enrolled over 1,700 patients. In December 2016, data collected with support of the EMBRACE study revealed genetic alterations in metastatic ER-positive breast cancer that are not seen in the disease before it spreads. These mutations could help the cancer evade therapies, so they could point to promising new targets for drugs that could beat drug-resistant cancer.

Learn More:

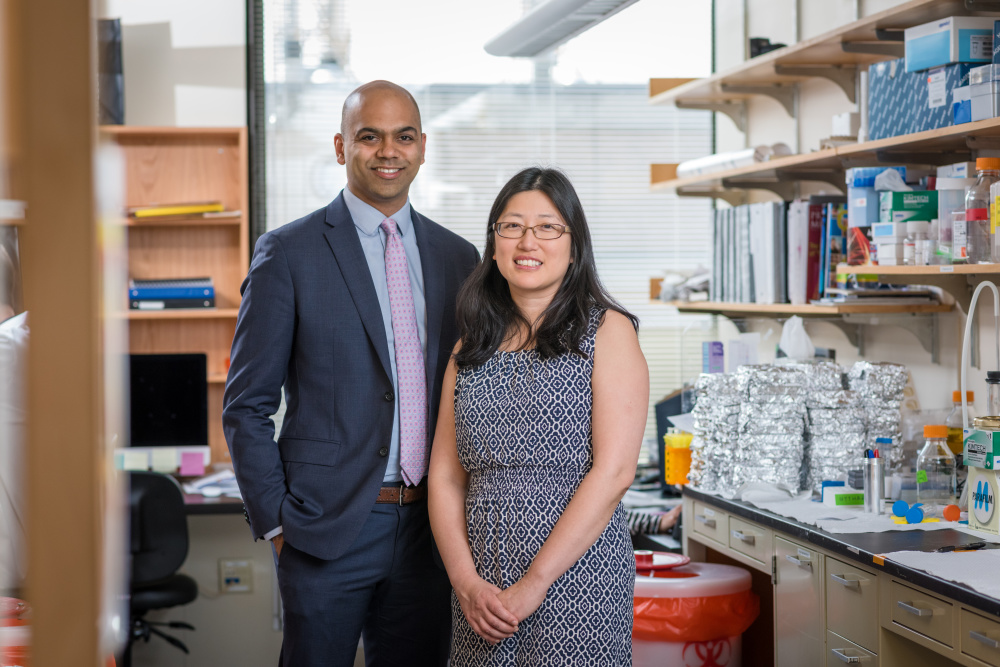

In the long run, combinations of new therapies could, conceivably, eradicate metastatic cancer or prevent it from becoming metastatic in the first place. “As we understand which drugs overcome resistance, our ultimate goal will be to try to cure metastatic breast cancer,” says Nikhil Wagle, MD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber.

Leads for new drugs are found faster by studying larger numbers of patients, so in 2015 Dr. Wagle launched the Metastatic Breast Cancer Project. It appeals to women and men with metastatic breast cancer across the U.S. to share tumor samples and medical records for research. The project, which is a collaboration between Dana-Farber and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, has enrolled more than 3,400 patients to date.

Dr. Wagle’s team reaches metastatic breast cancer patients through social media, although it is patients themselves who appeal to friends, support groups, and online followers to create a self-sustaining influx of new participants. “Patients put out an impassioned plea to others, telling them that it’s easy, and if you share your information, think of how much faster progress could be,” he says.

For Delling, her husband, stepchildren, siblings, friends, and career keep her fighting to live every day. But she is also inspired by the promise of research. “Every day they’re discovering,” she says. “There are disappointments, but there are also new drugs around the corner.”

This article originally appeared in Turning Point, which is published for supporters of the Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. To see the entire publication, please download the PDF version. If you’d like to receive a print version of Turning Point in the mail, please complete this form.