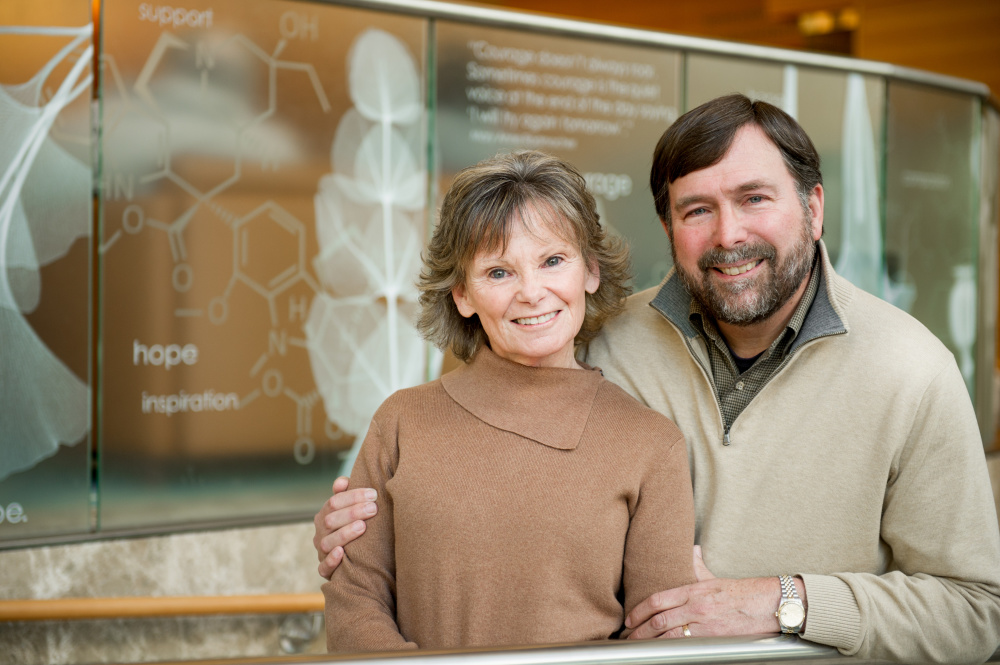

Deb Osborne is a retired elementary school teacher, not a football coach. But when explaining her role as the caregiver of a cancer patient – her husband, Allan – Osborne likes to draw on an analogy even non-sports fans can understand.

“A caregiver and a patient are a team, like a coach and a quarterback,” says Osborne. “You do a lot of work strategizing together beforehand, and then as the coach you send your quarterback into the action. Watching from the sidelines, you hope he or she can execute the game plan you’ve mapped out. And while you have a certain number of timeouts with which to restrategize, they are limited.”

Serving as Bill Belichick to Allan’s Tom Brady (the couple consider themselves loyal New England Patriots fans) is not a role that Osborne ever expected to play. Nine years ago, both Osbornes had recently retired from long careers in education and were happily contemplating the next chapter of their lives. Then, she says, “it was as if the entire book was suddenly written for us.”

Allan was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer, and began ongoing treatment at Dana-Farber. While resources were presented to Deb as a caregiver, she admits being so stunned by the turn of events that she didn’t seek them out. Instead, she focused her attention fully on her husband, putting his needs at the forefront and moving her own physical and emotional well-being to the back burner.

Learn More:

This reaction, explains Dana-Farber social worker Nancy Tharler, LICSW, is common for family members and friends who are helping a loved one with cancer.

“But just as a flight attendant instructs airline passengers to adjust their own masks before helping others in need of assistance, one of the most important things for family and friends to embrace when caregiving is to allow for their own self-care,” says Tharler. “This is difficult for people who now have less time, or may feel guilty or uncomfortable managing some of their own needs while their loved one is ill.”

One way caregivers can help themselves, says Tharler, is to share their feelings with others in the same situation – much as cancer patients do by joining support groups and online communities. Deb Osborne, who already volunteers at Dana-Farber as a way of giving back to the place that saved Allan’s life, recently took a big step in this direction by facilitating a peer-to-peer Caregivers Coffee Hour. During the sessions, which take place about once a month at Dana-Farber’s Eleanor and Maxwell Blum Patient and Family Resource Center, she leads a discussion in which caregivers share advice, encouragement, and even the occasional joke in a nonjudgmental setting.

“A friend suggested I should begin each coffee hour by telling my story, but then I realized that my story isn’t really any different from anyone else’s,” says Osborne. “We’ve all faced the same types of issues, and it’s very important for people to feel that this is a relaxed environment where everybody has a voice and we can find answers together.”

Topics run the gamut, from how to best prepare for a stem-cell transplant to dealing with a patient who becomes forgetful or angry when adapting to a new medication. Osborne’s advice for that one: step back, take a breath, and realize the frustration is not directed at you.

The coffee hours have been well-attended, and the feedback extremely positive. “I just needed to hear that my situation isn’t unique, and that coping skills work for others,” one attendee explained, while another said that “Talking about this topic, we could meet all day.”

The sessions are currently capped at 90 minutes, but Osborne is pleased to know they are working. Meanwhile, her journey with her husband continues.

“Our team has become more focused and ultimately stronger,” she says, returning to her football theme. “Much the same as all teams do when they play for multiple seasons. With time, you better understand each other’s strengths and use them to their fullest capacity. While each of you clearly plays a different position, you have the same ultimate goal.”