Cancer is the name given to a group of diseases in which cells begin to divide without control and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body. It becomes a health threat when cancerous cells crowd out normal cells or interfere with their ability to function.

Cancer can start virtually anywhere in the body. It results from abnormalities in genes that control when cells grow and divide, and when they die. These abnormalities can be inherited from one’s parents or can arise during one’s lifetime, either as a result of exposure to harmful factors in the environment such as tobacco smoke, certain chemicals, radiation, and ultraviolet light from the sun. They can also arise from bad luck – a mistake in copying DNA during cell division.

How Cancer Starts and Grows

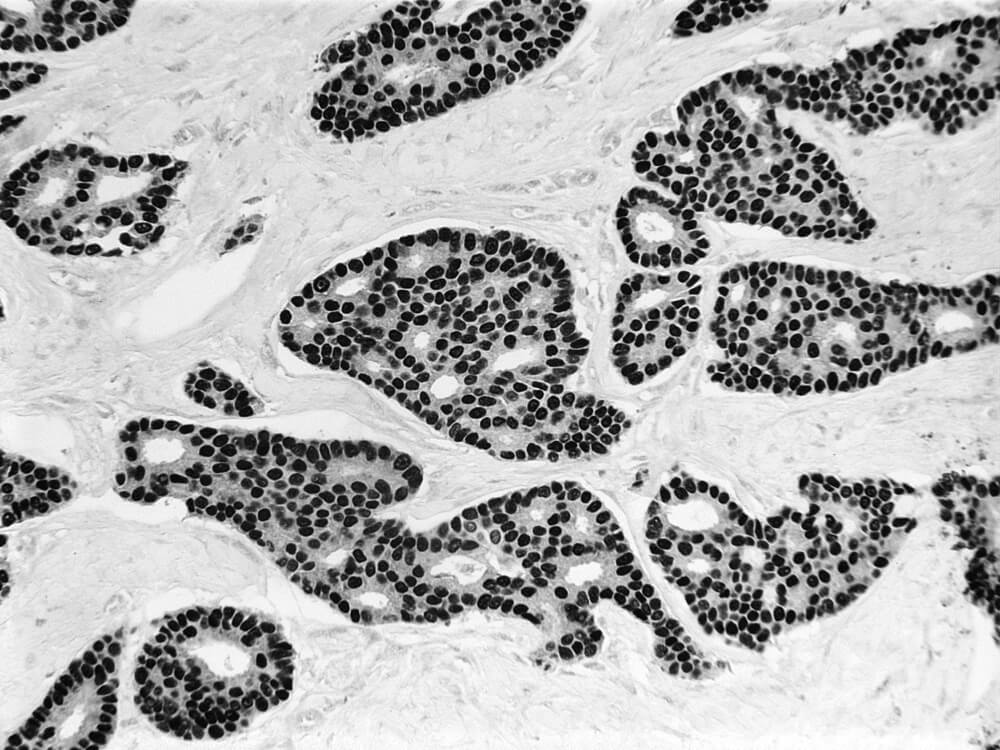

Cancer can start anywhere in the body and is usually classified by the organ or tissue where it originated, although, increasingly, it is also categorized by specific molecular abnormalities within the cancer cells themselves. Breast cancer cells designated “estrogen receptor-positive,” for example, have specific proteins on their surface that spur cell growth and division in response to the hormone estrogen.

More than 200 types of cancer have been identified. In the United States, the most common are non-melanoma skin cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

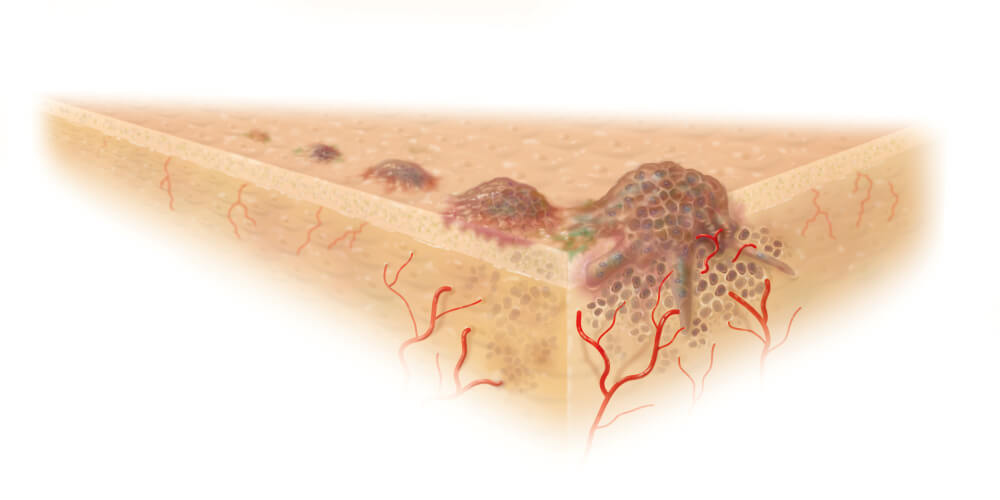

Some cancers form masses of malignant cells, known as solid tumors, in the body’s organs and tissues. Cancers of the blood and lymph systems – such as leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma – generally don’t form solid masses, but their presence can sometimes be signaled by swollen lymph glands.

The Difference — and Similarities — Between Cancer Cells and Normal Cells

Cancer cells differ from normal cells in a variety of respects. Normal cells divide in an orderly, consistent way, and die when they’re damaged or after they’ve divided a set number of times, allowing new cells to take their place. Cancer occurs when cells break free of these controls, dividing endlessly and not dying when they’ve reached their allotted number of divisions.

There are other differences as well. Cancer cells’ metabolism – their method for extracting energy and useful materials from nutrients – often varies from that of normal cells. And, critically, cancer cells often gain the ability to encroach on surrounding tissue and leave their site of origin and spread to other parts of the body, a process known as metastasis.

In some respects, however, cancer cells are very much like normal cells. A cancer cell is essentially a normal cell gone wrong, retaining some characteristics of the normal cell that gave rise to it. Like normal cells, cancer cells may develop the ability to tap into the bloodstream for nutrients. And like normal cells, many cancer cells manage to avoid an attack from the immune system.

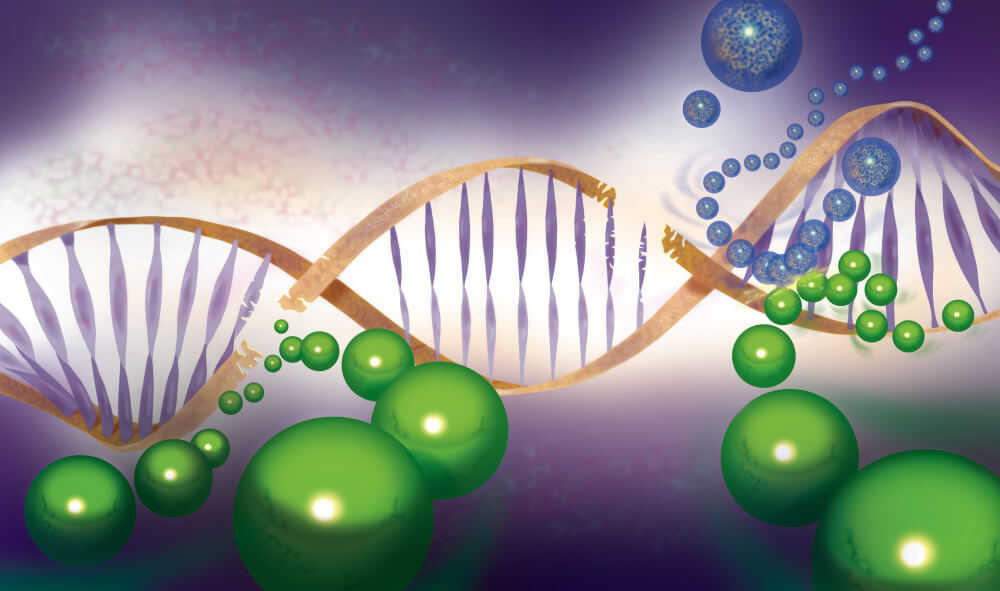

The genetic changes that can cause a cell to turn cancerous generally arise in three main types of genes: proto-oncogenes, tumor-suppressor genes, and DNA repair genes.

Proto-oncogenes are responsible for keeping cell growth and division under control. When these genes are altered or become overactive, cell division can run rampant. Tumor-suppressor genes are the brakes on cell growth and division. When they fail to function because of a mutation or other abnormality, the reins on division are loosened. DNA repair genes fix damaged DNA. When DNA damage occurs that would allow cell division to go into overdrive, DNA repair genes act to correct the damage. When DNA repair genes themselves are damaged, that correction may not take place.

How Cancer is Treated

Treatment for cancer takes a variety of factors into account: the type of cancer and its location in the body, its aggressiveness and stage of development, the overall health of the patient, and the cancer’s known susceptibility to certain therapies.

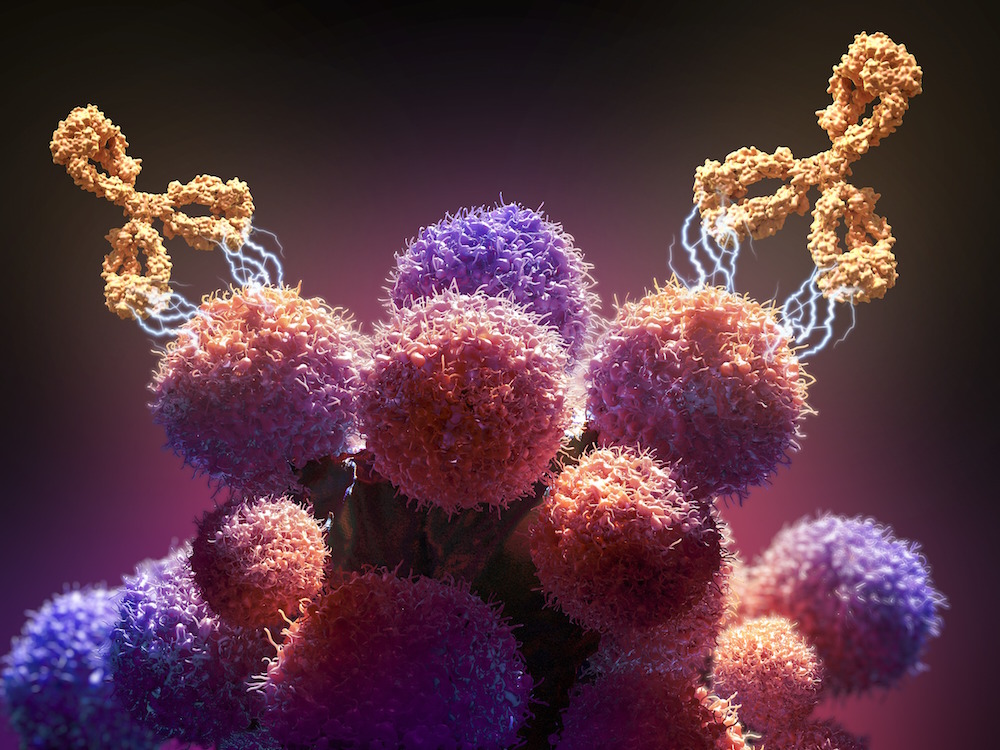

The three traditional mainstays of cancer treatment are surgery to physically remove tumors, radiation to kill cancer cells in specific locations, and chemotherapy to destroy cancer cells that may have dispersed or spread. In recent years, these have been augmented by targeted therapies, which disable the specific abnormal genes and proteins that drive cancer growth, and immunotherapies, which rally the immune system to better identify and destroy cancer cells.

Immunotherapies include therapeutic vaccines, which “teach” immune system cells to be more effective in fighting cancer; checkpoint inhibitors, which release the “brakes” on an immune system attack on cancer cells; and CAR T cells, which are specially engineered to take the battle to cancer cells.

Cancer has been known to physicians since antiquity, and scientific advances are constantly improving the odds in patients’ favor.

Learn more about cancer treatment from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.