Drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors – a type of cancer immunotherapy – have made one of the most impressive debuts of any type of cancer therapy, but their success has not been uniform across all types of cancer.

The drugs, which essentially lift the disguise that cancer cells use to evade an immune system attack, have achieved better results in some cancers than others. The reasons for this disparity aren’t completely clear, but researchers are confident that the potential of checkpoint inhibitors has only begun to be tapped.

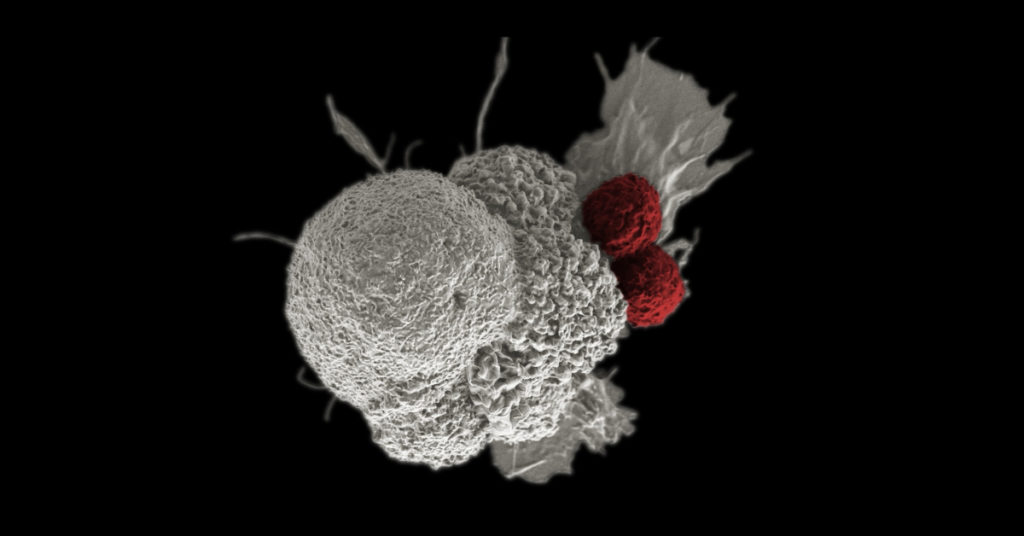

Checkpoint proteins exist on the surface of the body’s cells as a form of identification badge, informing the immune system that the cells are normal and not to be harmed. Cancer cells often appropriate these proteins for themselves, tricking the immune system into treating them as normal cells and leaving them unmolested. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs block these proteins – or the corresponding proteins on immune system T cells – allowing the T-cell attack on cancer to proceed.

The type of cancer in which checkpoint inhibitors scored their first success is melanoma. In clinical trials led by Dana-Farber’s F. Stephen Hodi, MD, ipilimumab, which blocks a checkpoint protein known as CTLA-4, became the first drug ever shown to lengthen the survival of patients with metastatic melanoma. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, ipilimumab produces a disease control rate of almost 30 percent (which includes patients who respond to therapy as well as those whose tumors are under control with no further growth).

A recent trial by Hodi and his colleagues showed the drug works even better – producing responses in more than half of patients –when combined with nivolumab, a checkpoint inhibitor that targets the PD-1 protein on T cells.

Other solid tumors that are vulnerable to PD-L1 or PD-1 inhibitors include non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), head and neck cancer, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, and some gastrointestinal cancers, including gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. In NSCLC, 40 percent of patients respond to checkpoint inhibitor therapy alone, meaning their tumors have either shrunk or stopped growing, while more than 50 percent respond when the drugs are used in combination with chemotherapy. Accordingly, the FDA has approved the checkpoint inhibitor/chemotherapy combination as front-line therapy for patients with NSCLC and as second-line therapy for patients who don’t benefit from initial treatment.

In head and neck cancers caused by the HPV virus, immune checkpoint inhibitors have produced beneficial responses in about 20 percent of patients in clinical trials, with about 80 percent of these responses continuing six months or more – a length of response often seen with checkpoint inhibitors.

Certain types of genitourinary cancers, including renal cell and bladder cancer, are also proving vulnerable. There are currently five immune checkpoint inhibitors approved for bladder cancer, a disease for which few good treatments have been available. The combination of checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilimumab and nivolumab is also starting to show promise in renal cell cancer, with more than 40 percent of patients showing a response to the drugs.

Checkpoint inhibitors are proving their value in some gastrointestinal cancers as well. The drugs were recently approved for patients with gastric cancer or hepatocellular carcinoma after producing good results in clinical trials.

“One of the most exciting recent developments was the FDA’s approval of checkpoint inhibitors for tumors with a feature known as microsatellite instability,” says Osama Rahma, MD, an immunotherapist and gastrointestinal cancer specialist in Dana-Farber’s Center for Immuno-Oncology and Gastrointestinal Cancer Treatment Center. “These tumors, also known as ‘MSI-high tumors,’ lack an enzyme involved in repairing DNA damage, which causes many abnormal proteins to appear on the tumor surface. These abnormalities make the tumors more visible to the immune system, and therefore more susceptible to immune checkpoint inhibitors. This hypothesis was proven in clinical trials, in which 40-60 percent of MSI-high tumors responded to the drugs.”

In the area of hematologic, or blood-related cancers, the PD-1 blocker nivolumab has generated a response in 70-80 percent of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) – the highest rate achieved by checkpoint inhibitors in any type of cancer. Proof of the effectiveness of the drug against HL was first demonstrated in clinical trials led by Dana-Farber’s Margaret Shipp, PhD, and Philippe Armand, MD, PhD.

It remains difficult to predict which patients with NSCLC are most likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors: It’s widely thought that patients whose tumor cells carry large amount of PD-L1 have the best chance of responding to the drugs, but the drugs sometimes work well in patients whose tumors have little PD-L1.

Ultimately, “the list of cancer types that respond to checkpoint inhibition is long and getting longer,” Rahma remarks.

There is general agreement among researchers and physicians that the key to extending inhibitors’ effectiveness to other types of cancer is combining the inhibitors with other therapies – other types of immunotherapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or anti-angiogenesis drugs (which deny tumors access to nutrients in the blood system). These strategies may help immune system cells penetrate the walls around cancer cells – turning so-called “immune desert” tumors into immune cell-rich tumors. “This is only the beginning of the era of cancer immunology,” Rahma observes. “It will only expand from here.”

Learn more about cancer treatment from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.