A year ago, Kelly Lamphere’s multiple myeloma was not responding to treatment, and her legs were so weakened by the cancer in her bones that she relied on a wheelchair and a walker. Today, because of CAR T-cell therapy, Lamphere’s disease is under control—and she can walk unaided again.

For most of 2017, Lamphere, 47, wasn’t sure how much time she had left. Her multiple myeloma, which for years had been stabilized by numerous chemotherapy regimens, along with a stem cell transplant in 2009, had begun outsmarting her treatment. Cancer built up in her bone marrow to the point where getting around was painful and tiring. While doctors near Lamphere’s home outside Syracuse, New York sought other treatment possibilities, it was apparent to her she was running out of options.

Then, in August 2017, Lamphere received a phone call that changed everything. A spot opened on a clinical trial in the Jerome Lipper Multiple Myeloma Center and LeBow Institute for Myeloma Therapeutics at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which had long partnered in her care. Trial participants were receiving CAR T-cell therapy, a form of immunotherapy that uses specially modified T cells—part of the body’s defense system against diseases—to attack cancer.

Robert Schlossman, MD, then Lamphere’s Dana-Farber oncologist, could not guarantee the therapy would work. It would require her to leave home and travel to Boston for several months, some of it spent as an inpatient. Still, given her deteriorating condition, he believed it was worth it.

“My disease was out of control, and Dana-Farber felt this was my best option,” says Lamphere, the mother of two teenagers. “I figured it was my last shot to see my kids grow up.”

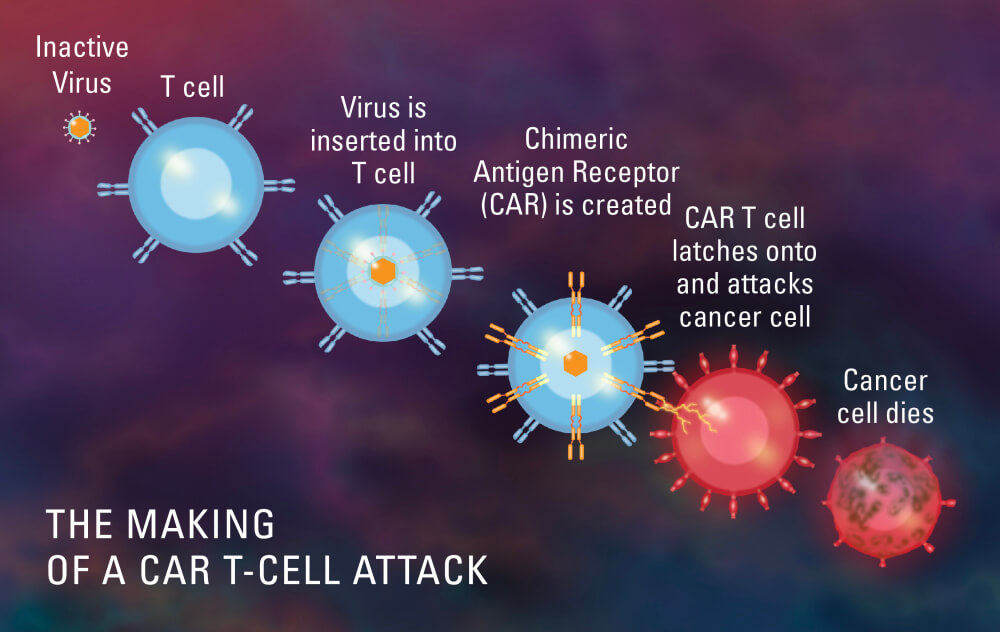

She took it, traveling to Boston with her husband, Chad, for a series of screenings to make sure she qualified for the trial. As the first step in the trial, each study participant had T cells separated from his or her blood by apheresis, after which the T cells were genetically engineered to produce proteins called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). Once reinfused into the bloodstream, trial leaders hoped, the modified T cells would use the CAR proteins to better recognize and eliminate cancer cells.

CAR T-cell therapy is a lengthy process with the risk of significant side effects. In Lamphere’s case, she experienced neurological problems that required a stay in the intensive care unit. Her husband stayed in Boston with her, and her children and parents visited, but she missed her son Jack’s entire football season. His phone calls recapping each week’s game were welcome diversions.

“Kelly certainly experienced some challenges from the treatment,” says Heidi DiPietro, RN, BSN, who manages the trial along with fellow Dana-Farber research nurse Kristen Cummings, RN, BSN. “The good news is that through the clinical trial, we’ve learned even more about how to best manage patients and their side effects— including having a neurologist involved in every case.”

For Lamphere, the trial—which is led by oncologist Nikhil Munshi, MD, director of basic and corrective science in the Lipper Center—has so far been successful. Her multiple myeloma has quieted again, and she is back home with her family in Syracuse. When she came to Dana-Farber for a three-month checkup this spring, neither a walker or wheelchair was needed.

“The study has highlighted a tremendous potential of CAR T-cell therapy in myeloma,” says Munshi. “The outstanding response shown in Ms. Lamphere’s case illustrates the power of immunotherapy, which has allowed her to be mobile again while improving her quality of life.”

And, most importantly to Lamphere, she is no longer missing any of her children’s sporting events. Recently she watched as her daughter Chelsea’s relay team sprinted to victory in a high school track meet, and offered a refreshing take on a longtime parental complaint.

“Hours of waiting, just to see her run for two minutes,” she says with a laugh. “After last year, it doesn’t bother me at all.”

Learn more about treatment for multiple myeloma from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.