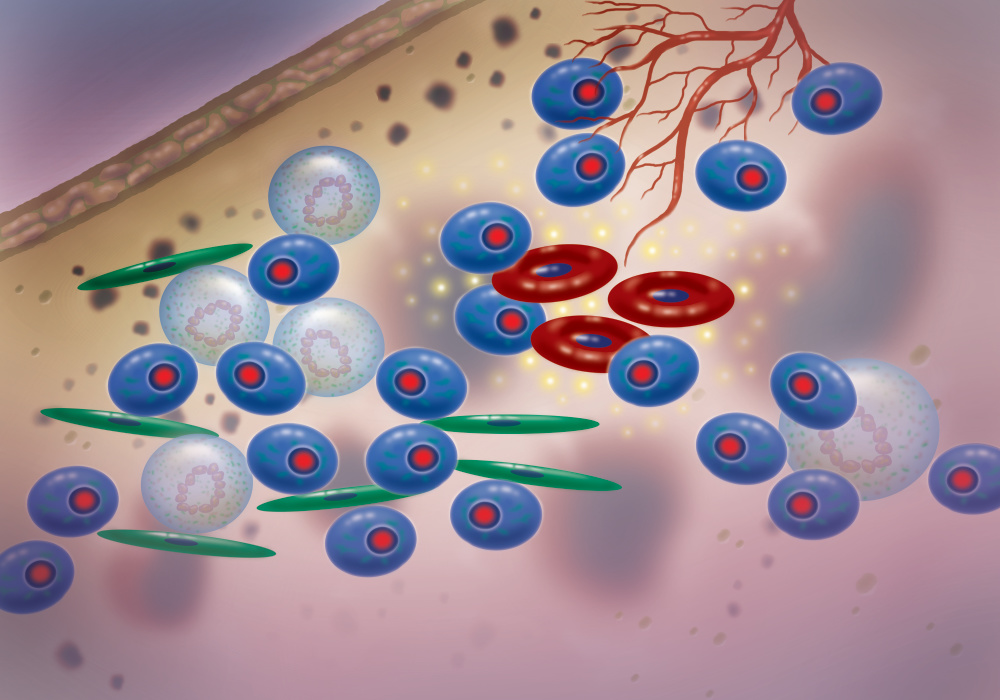

Multiple myeloma is a blood cancer in which the malignant growth of certain white blood cells within the bone marrow crowd out normal cells and attack solid bone. It is a genetically complex disease, with numerous different genetic changes underlying the cancer cells’ disordered growth.

Our cells have about 22,000 genes, which consist of DNA packed into chromosomes inside the cell nucleus. These genes control a wide range of functions, including cell growth and division. When the genes misbehave or mutate, cancer can develop.

Some of the common alterations seen in multiple myeloma involve abnormal exchanges of genetic material between two chromosomes—called translocations—which impact genes that control cell growth and division. Most often, these genetic exchanges occur between chromosome 14, one of the 23 pairs of chromosomes in humans, and another chromosome.

Researchers have identified certain genetic changes which, if found in a patient’s myeloma cells, predict poorer outcome and shorter survival, says Nikhil Munshi, MD, director of basic and correlative sciences at Dana-Farber’s Jerome Lipper Multiple Myeloma Center.

Some of those higher-risk genetic changes are translocations involving chromosome 14 with chromosomes 4, 11, or 16, and deletion of a section of chromosome 17. A particularly poor-risk genetic change is a combination of a 17p deletion with loss of the P53 tumor suppressor gene, which normally stops the formation of tumors.

Assessing a patient’s predicted outcome and risk through genetic analysis can enable tailored treatment for individual patients, according to Munshi. If a patient’s genetic analysis reveals an unfavorable genetic profile, the patient’s team may intensify or lengthen their treatment regimens, for example.

“We might use more high-risk treatments, like allogeneic stem-cell transplants,” Munshi explains. “And for maintenance treatment, where traditionally we might just give single drug lenalidomide, we may consider two different drugs” if the patient’s genetic profile suggests a lower survival prognosis, he says.

Tailored treatment in patients with an unfavorable genetic profile may include targeted therapies. A new type of cancer drug, venetoclax, works well in patients with a chromosome 11 to 14 translocation, according to Munshi.

In addition to chromosomal alterations, multiple myeloma patients may have DNA mutations in their cancer cells that can be targeted with certain drugs. Drugs known as MEK inhibitors often achieve a response when analysis reveals a KRAS or NRAS mutation in myeloma cells, says Munshi. The presence of a BRAF mutation suggests an inhibitor of that mutation may be helpful as well.

Immunotherapies, which have become standard treatment for some types of cancer, are currently in an experimental stage for myeloma. Munshi is leading a clinical trial of CAR T-cell therapy, a cancer treatment in which a patient’s immune T cells are genetically modified to mount a more effective attack on cancer. Munshi says this therapy has achieved a high rate of responses in multiple myeloma, “but the task is now to sustain these responses.”

Another approach to improving the outlook for high-risk myeloma patients is to strive for a state of absence or minimal residual disease, or MRD negativity. Traditionally, a patient would be considered in complete remission if tests showed no more than one myeloma cell in 100 bone marrow cells—which previously was the limit of detecting the cancer cells.

With new sequencing techniques, it’s possible to detect one myeloma cell in a million bone marrow cells—the definition of minimal residual disease. “We have shown that with minimal residual disease negativity, the outcomes are much better, almost inching toward a cure,” Munshi says.

Current treatments can’t achieve MRD as frequently in high-risk patients as in others; the hope is that therapies such as CAR T-cell therapy, used earlier in the course of the disease, might have greater success.

Learn more about multiple myeloma from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.