Lymphoma comes from a type of immune cell called a lymphocyte, which is important in helping your body fight infection. The two main types of lymphocytes are B lymphocytes (B-cell) and T lymphocytes (T-cell), and each has a slightly different function in the immune system. Each can also give rise to different lymphomas.

Although they arise from different types of lymphocytes, B-cell and T-cell lymphomas are both types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

B-cell lymphomas

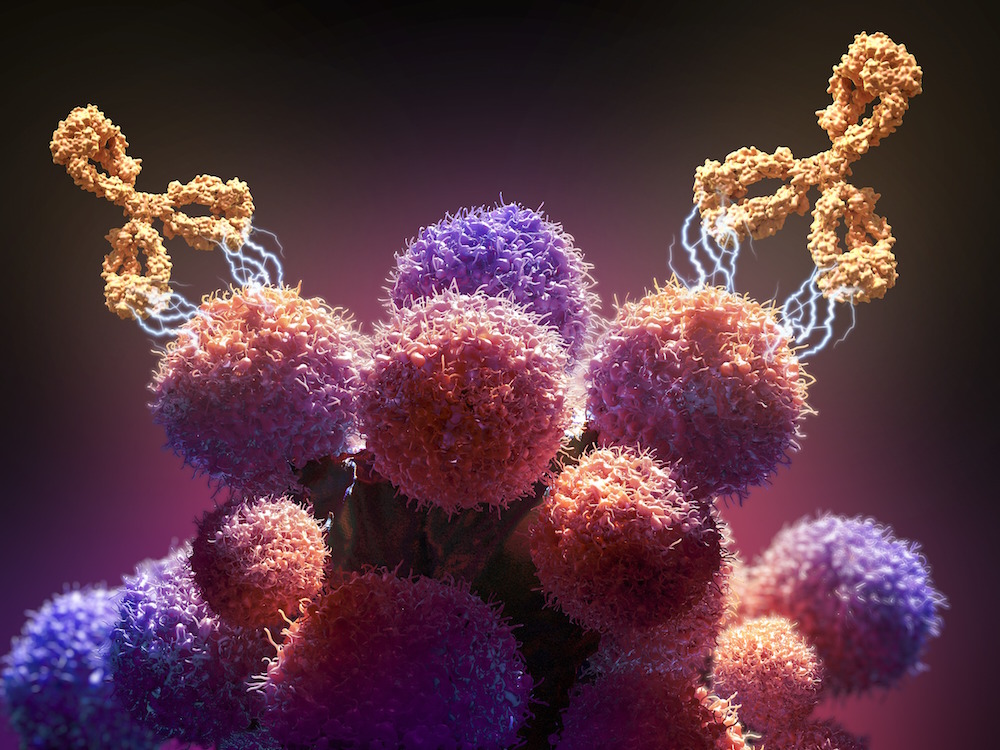

B cells help protect the body against viruses, and bacteria by producing antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that are created in response to foreign substances that trigger the immune system, called antigens. Antigens are often proteins on the surface of a virus or bacteria. The antibody attaches itself to the antigen and can directly destroy the “target” and/or trigger other cells in the immune system to destroy the “target.”

B cell lymphomas only affect the B lymphocytes and can either be slow-growing or aggressive. There are many types of B-cell lymphomas and treatment for B-cell NHL depends on what type you may have.

Some B-cell lymphomas include:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

DLBCL is the most common form of B-cell lymphoma. This type of lymphoma is fast-growing and often treated with a chemotherapy regimen of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in combination with a monoclonal antibody called rituximab, which is designed to target a protein on the surface of many B cell lymphomas. The R-CHOP regimen is given in three-week cycles, usually for six cycles thought the number of cycles can sometimes vary.

There are a variety of treatments for DLBCL that does not respond to or recurs after R-CHOP including other chemotherapies, stem cell transplant, and CAR-T cells.

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma

This kind of lymphoma forms in the space between the lungs (mediastinum). This is treated slightly differently than DLBCL, usually with a regimen called dose-adjusted R-EPOCH. This regimen combines rituximab with chemotherapy (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin). The R-EPOCH regimen is given as a continuous infusion 24 hours a day for four days in a row (the cyclophosphamide is given on the fifth day) and the doses of the chemotherapy are adjusted up or down, with each subsequent treatment depending on how the patient’s blood counts are doing.

There are a variety of treatments used for primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma in which R-EPOCH is not working, including radiation, other chemotherapies, and stem cell transplant. Other options include immunotherapy and CAR-T cell therapy.

Follicular lymphoma

Follicular lymphoma is typically slow-growing (indolent). Although the long-term prognosis is generally excellent, this lymphoma is a chronic disease in most patients and is not cured with chemotherapy. Stem cell transplant may cure some patients, but generally this type of treatment is reserved for highly selected cases after multiple other treatments, since patients can do very well for a very long time with much less aggressive treatment.

Early stage follicular lymphomas are often treated with radiation therapy and some patients with early stage follicular lymphoma may be cured by radiation.

Later-stage follicular lymphoma often does not require treatment as there is no advantage to immediate treatment in patients who have no symptoms or problems from their disease. When treatment is needed, the options are quite varied and may range from a monoclonal antibody (called rituximab) by itself or in combination with chemotherapy.

A newer antibody, called obinutuzumab, is also used sometimes in combination with chemotherapy. Newer pill forms of treatment called lenalidomide, idelalisib, and duvelisib are also used, particularly in patients who have received previous chemotherapy. Sometimes low doses of radiation are used in late stage follicular lymphoma if there is only one area that is growing or causing symptoms.

Sometimes follicular lymphoma can mutate, or transform, into DLBCL, in which case immediate treatment is required.

Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

SLL and CLL are nearly the same disease, with the difference being that CLL is characterized by a certain number of leukemia cells circulating in the blood whereas SLL is not. Both are chronic diseases that usually get worse slowly.

Early stage SLL or CLL may not require treatment if the patient has no symptoms or problems. Patients with more advanced stage disease or early stage disease with large lymph nodes or symptoms may need chemotherapy in combination with monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, though increasingly, patients are treated with targeted drugs such as ibrutinib or venetoclax rather than chemotherapy.

T-cell lymphomas

T cells, much like B cells, are vital to our immune system. While B cells produce the antibodies that target diseased cells, T cells directly destroy bacteria or cells infected with viruses.

Some T-cell lymphomas include:

T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia

This type of lymphoma is a fast-growing disease that is treated more like acute leukemia.

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL)

PTCL refers to a diverse group of aggressive lymphomas that frequently affect the lymph nodes, but also commonly occur in non-lymph node sites, such as thee bone marrow, spleen, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and skin.

Some types of lymphoma that make up a subgroup of PTCL include angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, and the most common: PTCL, not otherwise specified. The first line of treatment is often the CHOP chemotherapy regimen and is many times followed by a stem cell transplant.

ALCL is treated with a variation of the CHOP regimen in combination with an antibody treatment called brentuximab vedotin. Some rare types of T-cell lymphoma are treated with highly specialized chemotherapy regimens.

About the Medical Reviewer

Dr. Jacobsen received his MD from the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in 1999. He completed postgraduate training in Internal Medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital, followed by a fellowship in Medical Oncology and Hematology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. He joined the division of Hematologic Malignancies in 2005.