More than 60,000 new cases of adult leukemia are diagnosed in the U.S. each year. Although it is one of the more common childhood cancers, leukemia occurs more often in older adults.

How does leukemia develop in adults?

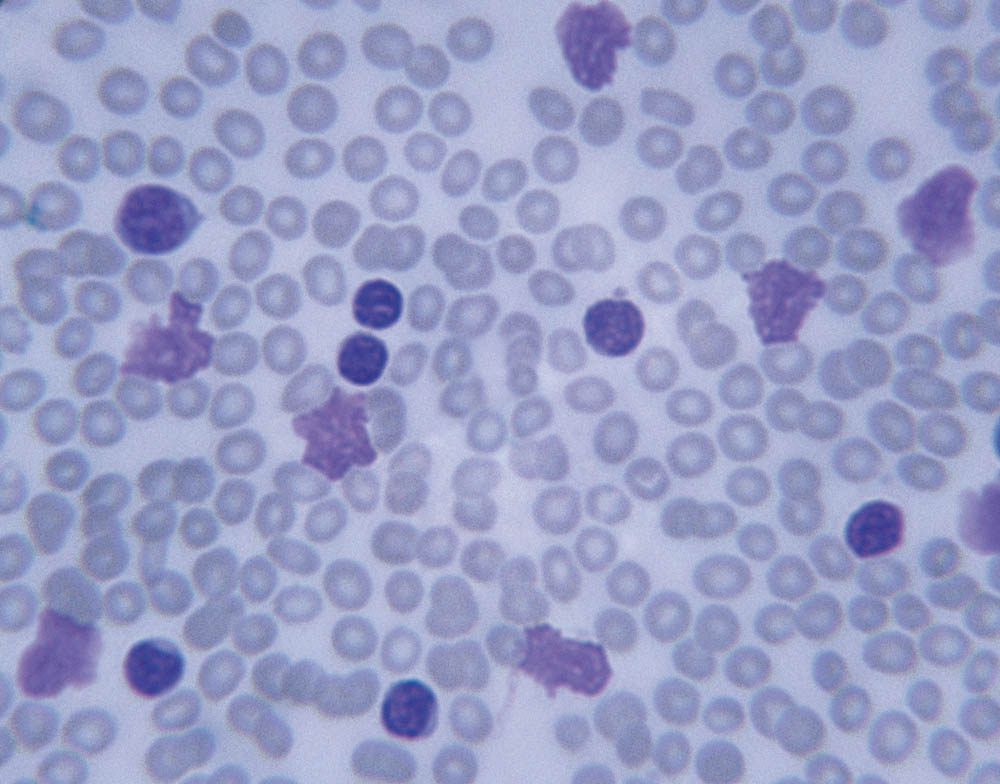

Leukemia is a cancer of the body’s blood-forming tissues that results in large numbers of abnormal or immature white blood cells. The main types of leukemia are:

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

AML causes the bone marrow to produce immature white blood cells (called myeloblasts). As a result, patients may have a very high or low white blood cell count, and low red blood cells and platelets.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

CLL is the second most common type of leukemia in adults. It is a type of cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many mature lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell).

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL)

ALL is a type of leukemia in which the bone marrow makes too many immature lymphocytes. Similar to AML, the white blood cells can be high or low and oftentimes the platelets and red blood cells are low. This form of leukemia is more common in children than adults.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)

CML is usually a slowly progressing disease in which too many mature white blood cells are made in the bone marrow.

What are the symptoms of leukemia?

People with leukemia may experience:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Bruising or bleeding easily

- Shortness of breath

- Pain or a feeling of fullness below the ribs on the left side

- Unexpected weight or appetite loss

- Night sweats

- Infections

- And/or enlarged lymph nodes.

Because these symptoms can be caused by a variety of other conditions, it’s important to check with your doctor if they arise.

What are the risk factors for developing leukemia?

While studies have shown men to be more at risk than women, some other risk factors include:

- Older age

- A history of smoking

- Prior treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy

- Heavy exposure to certain hazardous chemicals

- A history of a blood disorder such as myelodysplastic syndrome myeloproliferative neoplasm, or aplastic anemia

- Having certain genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, or dyskeratosis congenita.

How do doctors test for leukemia?

While test procedures vary based on the type of leukemia, the two most common procedures are the complete blood count (CBC) test and the bone marrow aspiration biopsy.

CBC is a procedure used to check the red blood cell and platelet counts as well as the number and type of white blood cells (the red cells carry oxygen, the white cells fight and prevent infection, and platelets control bleeding). A bone marrow aspiration biopsy involves removing a sample of bone marrow, including a small piece of bone by inserting a needle into the hipbone. The sample is then examined for abnormal cells.

How is leukemia treated?

Treatment for leukemia varies depending on the type and specific diagnosis.

Acute leukemias

The treatment for acute leukemias may be lengthy — up to two years in ALL — and is usually done in phases. The first phase, known as remission induction therapy, involves administering several chemotherapy drugs over a several-week period. The goal is to destroy as many cancer cells as possible to achieve a remission (in which cancer cells are undetectable, but small amounts are still present).

The second phase, known as post-remission or consolidation therapy, seeks to kill leukemia cells that remain after remission induction therapy. This phase may involve chemotherapy and/or a stem cell transplant.

Additional treatments may also be necessary. ALL patients, for example, may receive special treatment to prevent the disease from recurring in the spinal cord or brain.

Chronic leukemias

The treatment for CML has been revolutionized by the advent of the oral medication imatinib and the second- and third-generation drugs known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). These are oral medications that work to inhibit the function of the BCR-ABL protein. Many patients take these medications for the rest of their lives. In rare instances, a patient may require a stem cell transplant.

Some patients with CLL are recommended for monitoring and observation. Others, usually those with symptoms or low red cell or platelet counts, require treatment. Such treatment may involve intravenous chemotherapy, but often with oral therapy with pills that inhibit the function of a key protein, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase.

Treatments for leukemia can include:

- Chemotherapy

- Stem cell transplantation

- Targeted therapies — drugs that attack cancer cells by specifically targeting the abnormal proteins they need to survive.

- Other drug therapies — arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid, for example, are anticancer drugs used in treating a form of AML called acute promyelocytic leukemia.

- Radiation therapy — uses high-energy rays to damage or kill cancer cells and may be delivered to treat adult ALL that has spread or may spread to the brain or spinal cord.

Can leukemia be treated with immunotherapy?

Drugs that harness the immune system in fighting leukemia have shown considerable promise. Some monoclonal antibodies — synthetic versions of immune system proteins — are already in use to treat certain forms of leukemia and others are being studies in clinical trials.

Another form of immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, which release a pent-up immune system attack on tumor cells, is being tested in several forms of leukemia. Cancer vaccines, which boost the immune system’s ability to fight cancer, are being studied for use in leukemia.

CAR T-cell therapy, which uses modified immune system T cells to better target and kill tumor cells, has achieved impressive results in trials involving children and adults up to age 25 with relapsed ALL.

What else is new in leukemia research?

Research into new treatments for adult leukemia is moving along several tracks in addition to immunotherapy.

Genomic analysis of tumor cells

By tracking the specific abnormal genes within leukemia cells, physicians are increasingly able to tailor treatment to the unique characteristics of the disease in each patient. Targeted drugs such as imatinib and dasatinib, for example, are now used in treating patients with ALL whose leukemia cells have an abnormality known as the Philadelphia chromosome. Targeted agents including IDH or FLT3 inhibitors, which zero in on proteins made from mutated genes, have been approved to treat some patients with AML, while other such inhibitors are being tested in clinical trials.

More sensitive blood tests

New tests make it possible to detect ever smaller amounts of leukemia that remain after treatment. Investigators are exploring how these minute levels may influence a patients’ prognosis and how they might impact treatment.

Reducing treatment length

Researchers are testing whether treatment periods for certain drugs can be safely reduced in some patients. For instance, studies are under way to determine if drugs such as imatinib, which are currently taken for life, can be safely stopped in some patients with CML. Researchers hope to test whether treating patients with CLL with the drug ibrutinib plus other medicine for a fixed amount of time is safe and effective.

Patients may consider treatment through a clinical trial. Dana-Farber currently has more than 30 clinical trials for adult leukemia. A national list of clinical trials is available at clinicaltrials.gov.

For more information on adult leukemia, visit the website for the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center Adult Leukemia Program.

About the Medical Reviewer

Dr. Stone received his MD in 1981 from Harvard Medical School, his internal medicine residency training at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and his hematology-oncology fellowship at DFCI. He has performed numerous laboratory and clinical studies on acute leukemia and related disorders, and frequently participates in grand rounds worldwide. He is currently the Director of the Adult Acute Leukemia Program at DFCI, serves on the Medical Oncology Board of the American Board of Internal Medicine, and is vice chair of the Leukemia Core Committee for the national cooperative trials group Cancer and Leukemia Group B.