This post originally appeared on Vector, Boston Children’s Hospital’s science and clinical innovation blog.

It’s long been a mystery why some of our cells can have mutations associated with cancer, yet are not truly cancerous. Now researchers have, for the first time, watched a cancer spread from a single cell in a live animal, and found a critical step that turns a merely cancer-prone cell into a malignant one.

Their work, published recently in Science, offers up a new set of therapeutic targets and could even help revive a theory first floated in the 1950s known as “field cancerization.”

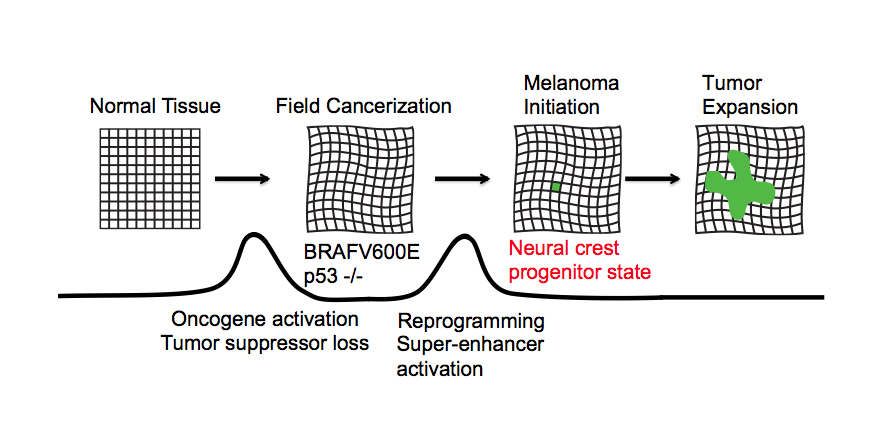

“We found that the beginning of cancer occurs after activation of an oncogene or loss of a tumor suppressor, and involves a change that takes a single cell back to a stem cell state,” says Charles Kaufman, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Zon Laboratory at Boston Children’s Hospital and the paper’s first author.

Clues in Crestin

Kaufman and colleagues tracked the development of melanoma over time, using the Zon lab’s preferred laboratory model: zebrafish. All the fish had the human cancer mutation BRAFV600E — found in most benign moles — and had also lost the tumor suppressor gene p53. Yet most did not develop cancer. Why?

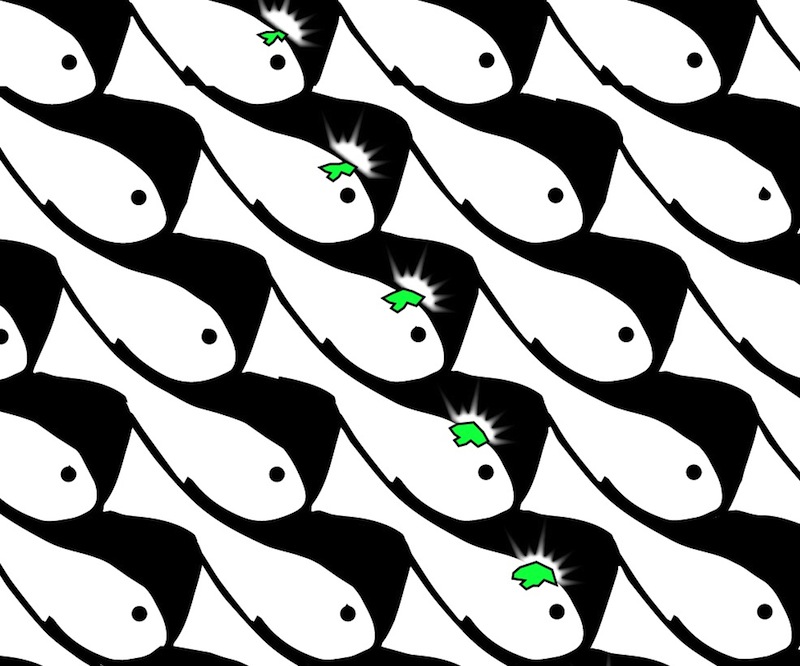

Acting on prior evidence, the team engineered the fish so that individual cells would light up in fluorescent green if a certain gene called crestin was turned on. Crestin served as a “beacon” indicating activation of a genetic program characteristic of stem cells. This program normally shuts off after embryonic development. But once in awhile, for reasons not yet known, crestin and other genes in the program turn back on in certain cells.

“Every so often we would see a green spot on a fish,” says Leonard Zon, MD, director of the Stem Cell Research Program at Boston Children’s and senior investigator on the study. “When we followed them, they became tumors 100 percent of the time.”

The Cell that Caused Melanoma

Finding these cancer-originating cells was tedious. Wearing goggles and using a microscope with a fluorescent filter, Kaufman examined the fish as they swam around, shooting video with his iPhone. Scanning 50 fish could take two to three hours. In 30 fish, Kaufman spotted a small cluster of green-glowing cells about the size of the head of a Sharpie marker — and in all 30 cases, these grew into melanomas. In two cases, he was able to see on a single green-glowing cell and watch it divide and ultimately become a tumor mass.

Looking more closely at these early cancer cells, Zon and Kaufman found that crestin and the other activated genes are the same ones that turn on when the zebrafish is still an embryo — specifically, in the stem cells that give rise to the pigment cells known as melanocytes, within a structure called the neural crest.

“What’s cool about this group of genes is that they also get turned on in human melanoma,” says Zon, who is also a member of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “It’s a change in cell fate, back to neural crest status.”

A New Test for Moles

Kaufman, also an instructor at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, estimates that only one in tens or hundreds of millions of cells in a mole eventually become a melanoma. Zebrafish are perfectly suited to this kind of numbers game.

“Because we can efficiently breed many fish, we can look for these very rare events,” Kaufman says. “The rarity is very similar in both humans and fish, which suggests that the underlying process of melanoma formation is probably much the same in humans.”

Zon and Kaufman believe that their findings could lead to a new genetic test for suspicious moles to see whether the cells are behaving like neural crest cells, indicating that the stem-cell program has been turned on.

Additionally, they’re investigating the regulatory elements that turn on the genetic program (known as super-enhancers). These DNA elements have epigenetic functions that are similar in zebrafish and human melanoma, and could potentially be targeted with drugs to stop a mole from becoming cancerous.

A Paradigm Shift for Cancer?

Zon and Kaufman believe their findings have relevance to most if not all cancers, not just melanoma. Going back to the old concept of field cancerization, they propose that normal tissue becomes primed for cancer when oncogenes are activated and tumor suppressor genes are silenced or lost, but that cancer develops only when a cell in the tissue reverts to a more primitive, embryonic state and starts dividing.

Read more on this study in the New York Times. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA103846), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (K08 AR061071), the Ellison Foundation, the Melanoma Research Alliance, the V Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Leonard Zon is a founder and stockholder of Fate, Inc. and Scholar Rock.

Great article. Great patient education info. Glad to be a breast cancer survivor as well as a health care provider who can educate patients to the latest.

Question, if the cells are being taken back to a stem cell state, what differentiates the embryo state (e.g growing baby) from this reverse to the stem cell state? What causes the embryo stem cells to shut off when a baby is first forming to keep babies from developing cancer? Or stating another way, when the cells are taken back to their stem cell state, how can scientists shut them off to that they dont become cancerous?