Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer both involve enlargement of the prostate, the walnut-sized gland that produces fluid that makes up a portion of semen. The prostate sits below the bladder and surrounds the urethra, the tube that carries urine out of the body. When the prostate increases in size, whether due to BPH, cancer, or other cause, it can narrow the urethra and create problems in passing urine. These can include a more frequent urge to urinate, decreased urine flow, a need to get up several times a night to urinate, and a burning sensation while urinating.

The prostate tends to grow larger as men age, often due to BPH, a non-cancerous or benign condition involving excessive growth of normal prostate tissue. More than half of men in their 60s, and an even higher percentage of men in the 70s and 80s, show signs of BPH. Having BPH does not increase one’s risk of developing prostate cancer, even though the symptoms of the two conditions can be similar.

Prostate cancer arises when tumor cells begin to form and multiply in the gland, causing it to expand. As opposed to BPH, which is a diffuse process, prostate cancer can be located in different parts of the prostate. This may cause problems with urination and ejaculation if the cancer gets very large. Usually, however, prostate cancer is found in absence of symptoms when men undergo routine testing.

The American Cancer Society recommends that men be tested for prostate cancer beginning at age 50 if they are at average risk for the disease (meaning they don’t have a strong family history of it) and have at least a 10-year life expectancy. Testing is recommended at age 45 for men with a first-degree relative (father, brother, or son) diagnosed with prostate cancer before age 65, and at age 40 for those with more than one first-degree relative diagnosed before 65. There are essentially two components to testing: a digital rectal exam, in which a physician uses a gloved, lubricated finger to feel the size, firmness, and texture of the prostate; and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, which measures the blood level of a protein that often rises when prostate cancer is present.

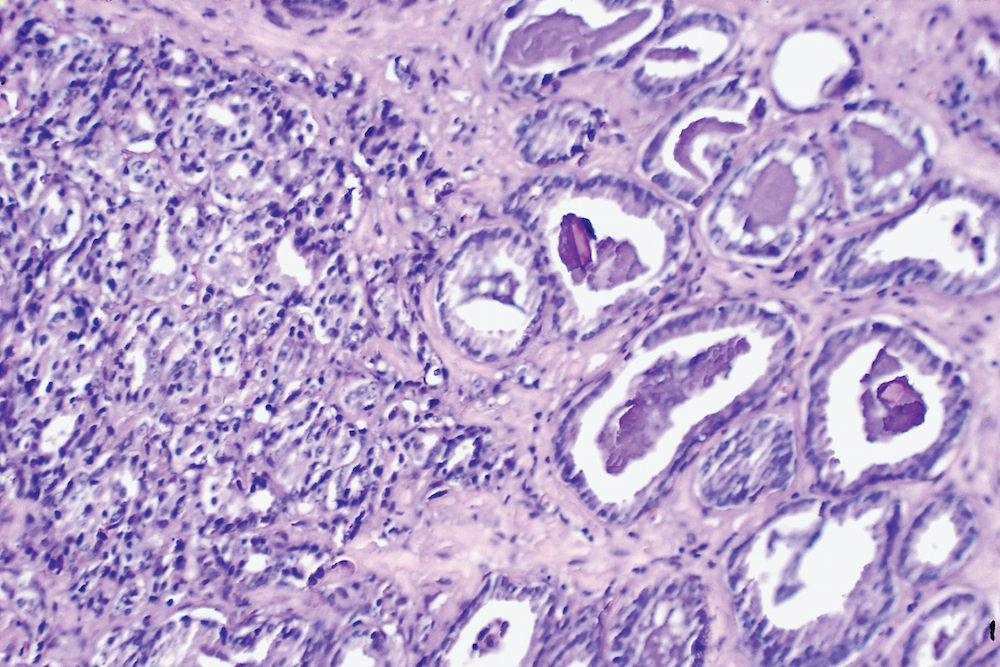

If the prostate feels abnormal or the PSA reading is unusually high, a urologist will perform a biopsy, in which small samples of prostate tissue are removed for examination by a pathologist. The exam will indicate whether prostate cancer cells are present and how aggressive they are. While some forms of prostate cancer may metastasize, or spread to other parts of the body, it is important to note that some prostate cancer cells have very little chance spreading. When a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer that is felt to be non-aggressive, no intervention may be necessary.

If the biopsy results are negative for cancer, the cause of prostate enlargement may be determined to be BPH. (Enlargement can also be caused by prostatitis, an inflammation of the prostate that may result from a bacterial infection.) For many men, the problems associated with BPH, if bothersome, can be manged with drug therapy such as alpha blockers or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors. If they become very severe or medications are ineffective, they can be dealt with by surgery to open the urethra or, in cases of severe obstruction or a very large prostate, removal of the prostate.