Retinoblastoma is a rare childhood cancer of the eye. It arises from the retina, the nerve tissue in the back of the eye that is sensitive to light. Advances in diagnosis and treatment mean that now, 95 percent of children with retinoblastoma can be cured.

More than 90 percent of cases are diagnosed by age five, and the disease is equally common in boys and girls. The tumor(s) may be present in one or both eyes, and rarely spreads to other parts of the body. Retinoblastoma may be inherited within a family or may occur in a child without any family history of the disease.

Retinoblastoma symptoms tend to develop before age two. The most common symptoms include:

- Leukocoria, when the pupil of the eye appears white instead of the expected red when light shines into it. This effect is also often seen in photos that are taken with a flash. Rather than the typical “red eye,” the pupil may appear white or distorted.

- Strabismus (also called “wandering eye” or “crossed eyes”) – one or both eyes don’t appear to be looking in the same direction

- Nystagmus – involuntary movement of the eye(s)

- Poor vision or change in vision

- Pain or redness around the eye(s) (rare)

Retinoblastoma is usually found before it spreads outside of the globe (the eyeball itself), and there are several types of treatment that can save sight in the affected eye.

The retinoblastoma treatment team at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders frequently uses intra-arterial chemotherapy as a treatment approach, as it offers several advantages as compared to traditional forms of treatment for retinoblastoma.

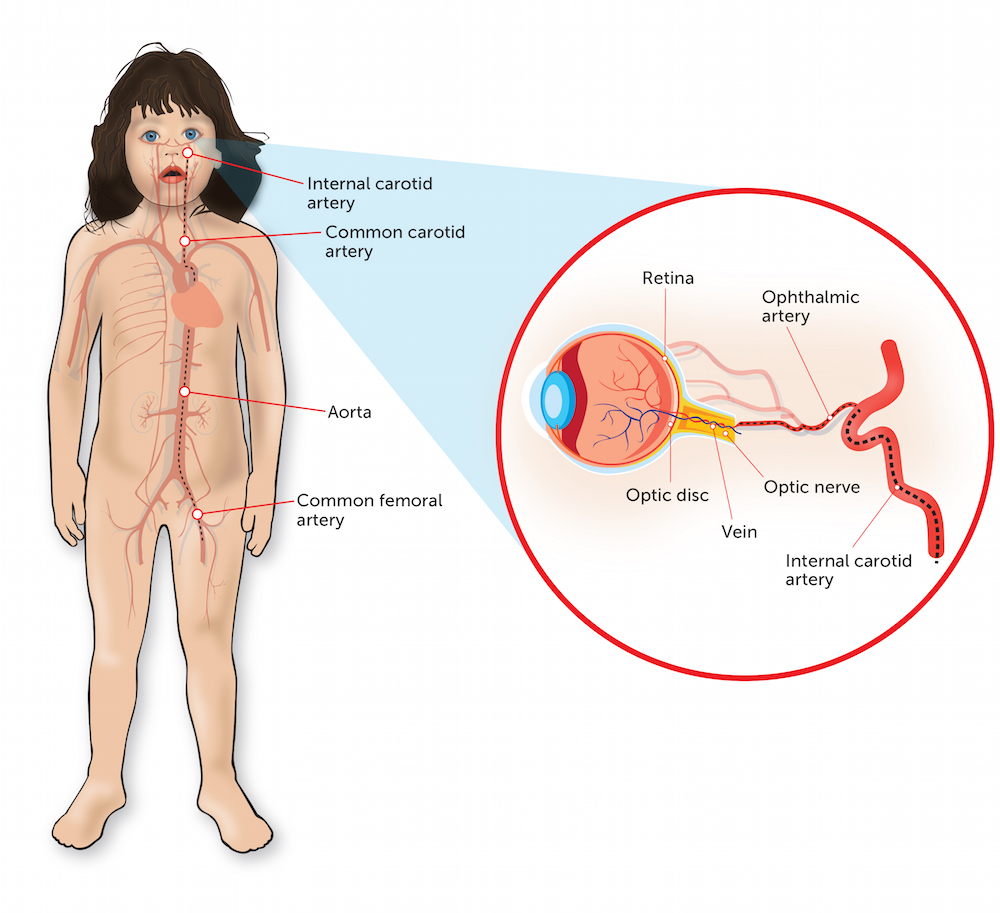

In intra-arterial chemotherapy, the chemotherapy is injected directly into the main blood vessel supplying the eye (the ophthalmic artery) through a tiny catheter. This treatment was designed to minimize the amount of chemotherapy delivered to the rest of the patient’s body, so as to reduce side effects.

Learn More:

Even though the total dose of chemotherapy injected is lower than in traditional IV treatment, the dose delivered directly to the eye itself is much higher, since the drug does not have to travel through the intravenous route and fill all the arteries of the body in order to get to its target. In this way, more cancer cells can be killed that may be possible with intravenous injection. The eye is uniquely suited to intra-arterial chemotherapy because the blood supply to the eye, in almost all cases, travels through just one feeding artery.

Intra-arterial chemotherapy also has advantages over other types of treatment. Standard IV chemotherapy treatment introduces chemotherapy to the entire body, rather than to one small area, and can cause systemic symptoms, such as a weakened immune system. And unlike surgery for retinoblastoma, intra-arterial chemotherapy also offers the opportunity to preserve a child’s vision. Radiation treatment, such as through proton beam therapy, exposes the target organ and the tissue around it to radiation, which can potentially induce a secondary tumor down the line.

Still, pediatric and adult patients have their own unique needs, and should be treated accordingly, according to Darren Orbach, MD, PhD, Chief of Neurointerventional Radiology at Boston Children’s Hospital, who performs intra-arterial chemotherapy for retinoblastoma patients.

“Unfortunately, a relatively high rate of adverse events has been seen with this treatment when it is performed by practitioners who typically treat vascular conditions only in adults,” says Orbach. “The approach to catheterizing the infant cerebrovascular system is unique, and intra-arterial chemotherapy for retinoblastoma is most safely done at centers with a high volume of pediatric cases.”

Learn more about retinoblastoma treatment from Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s.