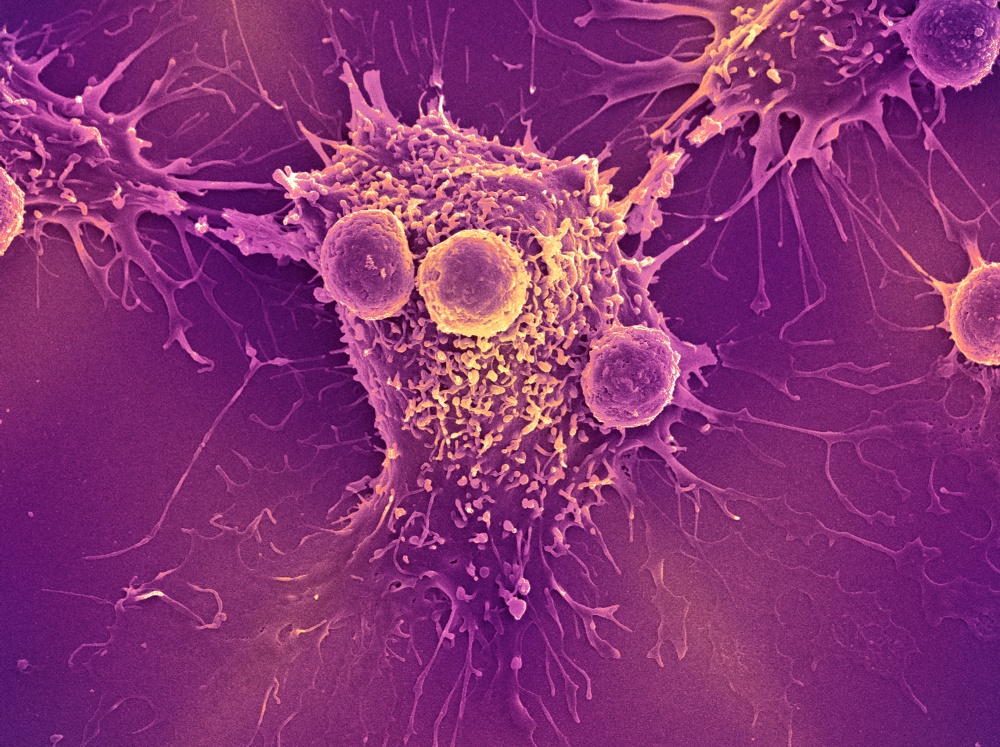

The past two years have seen striking changes in treatment of advanced bladder cancer, mainly the approval of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs as second- or third-line options for patients after chemotherapy, or in some patients who can’t tolerate the usual chemotherapy regimen. These drugs unleash the activity of immune cells to target and kill cancer cells.

Most patients with localized muscle-invading bladder cancer receive some combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy; chemotherapy combinations usually include agents containing platinum, such as cisplatin or carboplatin.

Beginning in 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved five checkpoint inhibitor drugs for patients whose advanced or metastatic bladder cancer has progressed following treatment with platinum chemotherapy: pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, durvalumab, and avelumab. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab are also approved as first-line treatment for some patients with advanced bladder cancer who can’t tolerate platinum chemotherapy because of poor general health or kidney function or other illnesses.

Although these immunotherapy agents are, as of now, effective in inducing response only in 15 or 20 percent of patients treated with them, “most of the responses are very durable,” says Guru Sonpavde, MD, who leads the bladder cancer treatment center at Dana-Farber.

“Pembrolizumab has demonstrated improved survival with the duration of response exceeding a median of two years in a phase 3 trial in patients who had progressed following platinum chemotherapy,” Sonpavde adds.

Newer clinical trials are underway that aim to test the potential role of checkpoint inhibitors as first-line treatment for all patients with advanced bladder cancer. They are being evaluated in combinations with platinum-based chemotherapy and in combinations of two different checkpoint inhibitors, Sonpavde says.

Immunotherapy and Surgery

Surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding organs, called a radical cystectomy, may be needed to treat cancer that has invaded the muscle layer of the bladder. In an effort to reduce the size of the tumor in these cases and improve the cure rate, a new area of research is examining the use of checkpoint inhibitors before surgery, a practice known as neoadjuvant therapy, according to Sonpavde.

“This neoadjuvant setting is exciting to us, because when the tumor is still in place, there are a lot of neoantigens sitting around that could train the immune system to detect and attack cancer cells that have spread beyond the bladder,” Sonpavde says.

Neoantigens, which are proteins created by genetic changes in cancer cells, help the body’s immune system, if activated, to recognize the cancer as foreign and go on the attack against it. Preliminarily, checkpoint inhibitors appear promising as neoadjuvant therapy, and multiple large randomized trials are investigating adjuvant or post-operative therapy with these drugs—for example, to improve the cure rate after surgery to remove muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Unlike with many other types of cancer, there are currently no approved molecularly targeted drugs for bladder cancer, but several such drugs are showing promise in clinical trials. One, an antibody compound known as enfortumab vedotin, targets a protein expressed on cancer cells. It has received breakthrough designation from the FDA—meaning it has been granted priority review based on early clinical trials suggesting it may have significant advantages over current treatments—and is being evaluated in patients with locally advanced or metastatic bladder cancer who previously had checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

The targeted agents erdafitinib and rogaratinib are aimed at the fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3), which is altered in some cases of metastatic bladder cancer. Early clinical trials results with these targeted drugs show promise, according to Sonpavde.