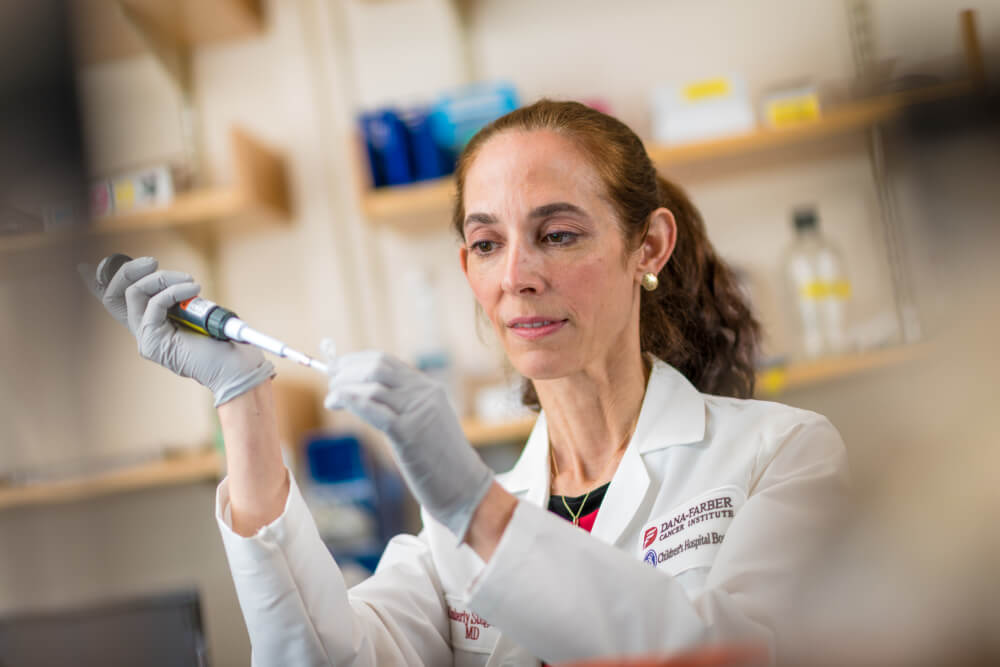

Pediatric oncologist Kimberly Stegmaier, MD, chronicles her long tenure at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center not only in years—24—but in connections.

From her earliest days as a Harvard Medical School student, to her current roles as co-director of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Pediatric Hematologic Malignancy Program and vice chair of Pediatric Oncology Research at Dana-Farber, Stegmaier has formed not only strong ties with a multitude of talented colleagues across specialties, but also close bonds with a generation of young cancer patients and research assistants whom she still calls “my kids.”

“What attracted me to medicine, in part, was my love of children and young people and the nurturing you can provide them,” she says. “It’s amazing to witness their growth; it’s a joy like no other.”

Those valued—and valuable—connections have fueled Stegmaier’s cutting-edge research into new treatments for pediatric patients with leukemia, Ewing sarcoma, and neuroblastoma.

“We have such a collaborative atmosphere here,” she says. “It really is the ‘secret sauce’ of Dana-Farber. Everyone really works as a team with the patients’ best interests at heart.”

From Research to Better Treatments

Stegmaier’s laboratory team, featuring researchers from Dana-Farber, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, is applying the latest “omic” approaches to better understand how leukemia and solid tumors develop—and to identify their Achilles heels. “Omics” refers to large amounts of data that researchers collect on molecules—genes, proteins, RNA—to find novel therapeutic targets and, ultimately, better drugs.

Among her ongoing research efforts, Dr. Stegmaier is co-leading the generation of the Pediatric Cancer Dependency Map. A collaboration with the Broad Institute, this large-scale effort uses genomic testing to look for potential treatment targets in pediatric cancers. So far, researchers have tested nearly 100 pediatric cancer cell lines—samples of a specific type of cancer cell that researchers continue to grow and divide in the lab.

“Many of the genetic changes that occur in childhood cancers have been hard to combat with drugs,” she explains. “So, we’re using CRISPR technology to knock out genes, one by one, to determine which genes the cancer cells are dependent on.”

Several of Stegmaier’s recent research collaborations with Dana-Farber colleagues have contributed greater detail to that critical map. As they reported in the August 20 issue of Nature Genetics, Stegmaier and A. Thomas Look, MD, professor of pediatrics and a researcher in Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Department of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, identified a set of critical dependency genes in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma that are essential for cell state and survival in the tumor.

“By collaborating, we can quickly move from an idea to generating a compelling body of data to validate the hypothesis,” Stegmaier says.

In another case, Stegmaier was contacted by Nathanael Gray, PhD, a Dana-Farber chemical biology researcher, about an intriguing intersection between his work and hers. As they reported in the January 2018 issue of Cancer Cell, their joint work identified a promising combination of two inhibitors that proved highly effective in killing Ewing sarcoma cells by exploiting the sensitivity of these cells to repression of DNA damage repair.

“Omic” research continues to uncover even more new pathways for treatment. For example, Stegmaier and colleague Loren Walensky, MD, PhD, a chemical biology researcher and physician in Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Department of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, were about to wrap up their study of new therapeutic strategies to reactivate the TP53 tumor suppressor pathway in Ewing sarcoma, when they discovered that targeting the USP7 gene could be another Achilles heel of this pediatric cancer. It turned out that Sara Buhrlage, PhD, a chemist at Dana-Farber, had just developed a promising small molecule inhibitor of USP7. She sent them a sample within 24 hours of hearing of their work, and it succeeded in activating TP53 to kill Ewing sarcoma cells.

“These discoveries are thrilling,” Stegmaier says. “Each day is an opportunity to advance our knowledge of pediatric cancers, and each day there is the possibility of a new finding that will impact the care of the children with cancer.”

A Love for Mentoring

Stegmaier’s fondness for her laboratory trainees recently earned her the Casty Family Achievement in Mentoring Award. She’s proud to point out that several of “her kids” have gone on to launch labs of their own, and she celebrates their advances as much as her own in unlocking potential treatments for the next generation of young patients with cancer.

“As a physician-scientist, I have the real privilege of taking care of children and their families,” she says. “In the lab, we are working for the children whom we do not succeed in curing. I cannot imagine a more compelling motivation. But, we are hopeful that through innovative research we will see a time when we will find cures for every child with cancer.”