- Tests on living “organoids” created from patients’ ovarian cancer cells proved more accurate than DNA sequencing in predicting tumors’ sensitivity or resistance to chemotherapy drugs.

- Ovarian cancer organoids were developed from patient tumor samples in just seven to ten days, instead of weeks or months, allowing for rapid, direct tests of drugs and drug combinations.

- The organoids created in this study were found to contain immune cells, raising the prospect of testing immunotherapy drugs for ovarian cancer, the scientists say.

Tests on living “organoids” created from patients’ ovarian cancer cells proved more accurate than DNA sequencing in predicting tumors’ sensitivity or resistance to chemotherapy drugs – and combining the two methods worked even better, say scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

The investigators report in Cancer Discovery that ovarian cancer organoids – tiny, three-dimensional spheres of cells modeling a tumor – were developed from patient tumor samples in just seven to ten days. By contrast, organoids created for other solid tumors, such as pancreatic, colon, and prostate cancers, can take weeks or months to form, by which time the cancer cells may have undergone genetic changes making them less similar to the patient’s cancer.

“Because ovarian tumor organoids grow so quickly, we can do rapid, direct tests of drugs and combinations of drugs to predict a patient’s response,” says Alan D’Andrea, MD, senior author of the report, and director of Dana-Farber’s Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers and the Center for DNA Damage and Repair.

D’Andrea cautioned that larger studies will be needed to validate the reliability of ovarian cancer organoids and meet regulatory standards.

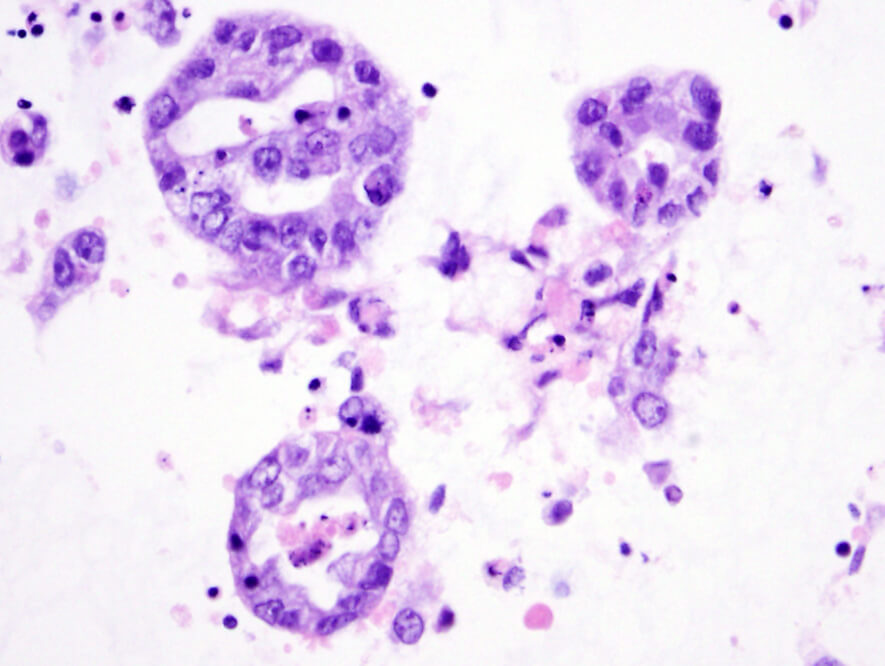

From the O.R. to the lab

The report, whose first author is Sarah J. Hill, MD, PhD, a pathologist at Dana-Farber and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, described 33 organoids created from 22 patients with high-grade ovarian cancer. Hill obtained ovarian tumor tissue from the operating room, with the help of her gynecologic oncology surgical colleagues at Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and used the cells to grow organoids in the laboratory. Each organoid, comparable in diameter to the period at the end of a typed sentence, contains 100 to 200 cancer cells. Remarkably, 90 percent of the patient samples developed into usable organoids – a much higher success rate than in other types of solid tumors. Moreover, the organoids were found to contain immune cells, raising the prospect of testing immunotherapy drugs for ovarian cancer, the scientists say.

Because many high-grade ovarian cancers are weakened by DNA changes that impair the tumor cells’ ability to repair genetic damage, drugs that target that vulnerability are a mainstay of chemotherapy. Initial treatment, in addition to surgery, is usually a combination of a platinum-based drug that damages DNA and another drug, paclitaxel. Currently, there is no adequate way to predict which patients’ tumors will be sensitive to platinum drugs, and many patients develop resistance to them.

Another class of drugs, PARP inhibitors, kill tumor cells with crippled DNA damage repair mechanisms. High-grade ovarian cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations often respond to PARP inhibitors, but no current tests can predict which patients will have responses. New classes of drugs, such as ATR and CHK1 inhibitors, may be effective when PARP inhibitors are not.

Organoids predict DNA repair status

Genomic testing is currently used to predict sensitivity to DNA-damage repair drugs. However, “We determined that genomic data alone cannot accurately predict the true DNA repair capacity of high-grade ovarian cancers, and that a rapid functional platform is needed for targeted drug selection,” Hill says.

One significant finding was that most of the organoids were not sensitive to the PARP inhibitor olaparib, indicating that the tumors did not have defects in homologous recombination – a type of DNA damage repair – even though genomic testing had indicated that many of them would have these defects. “Although the low rate of PARP inhibitor sensitivity is surprising, our results are more accurate than genetic predictions alone,” said Hill. The organoids also shed light on other mechanisms of sensitivity or resistance to DNA-damaging agents.

The investigators also note that “in many cases, the drug response of the organoid cultures correlated well with the clinical response of the corresponding patient.” Illustrating the potential value of the organoid platform, “in a couple of cases we were able to alter the management of the patient and switch to a different drug,” says D’Andrea.

He emphasizes that the greatest barrier to preventing deaths from ovarian cancer remains the lack of an early detection method: “We don’t have that yet,” he says. But meanwhile, the organoid platform could have value in choosing therapies for women diagnosed with current technologies.

I have stage 4 ovarian cancer and am currently fighting it for my fourth time. I’m hopeful about the progress being made. Thank you for your hard work in research.

Are ovarian cancer organoids developed from all patient tumor samples obtained at Dana Farber? If so, would patients have access to the results from their samples? Is it possible to create organoids from all the different OC histologies?

Thank you Susan for the comment. Right now, the ovarian cancer organoids developed were only part of a small research study. Larger studies are needed to validate their reliability.

How you test the drugs? microinjections or diluted in the culture media?