If you have had a biopsy or surgery that removes tissue from your body, in almost all cases a sample will be sent to a pathology lab for examination. Pathologists, who specialize in looking at microscopic tissue samples, will look for signs of disease.

Their findings will be detailed in a pathology report. The first section will contain their overall diagnosis. The rest of the document will provide details.

In the US, a patient will receive the pathology report as soon as the pathologist files it, so you might see it before your physician does. It’s important to know a few things about pathology reports before you look.

Pathologist Stuart Schnitt, MD, has one piece of advice: “If a patient doesn’t understand something in the report, they should talk to their doctor about it. Don’t try consulting the internet. It’s too easy to be misled and jump to conclusions that cause unnecessary anxiety.”

Are there parts of the pathology report that I should look at?

If the pathologist found disease in your tissues, a Final Diagnosis section, typically at the top, will describe the disease.

Please note that the report will provide many details whether there is a diagnosis of cancer or not. The terms used may be technical and difficult to understand without context or expertise.

The best practice is to review your report with your doctor. If you do receive a cancer diagnosis, your doctor will help you understand the important details, such as the origin of the cancer in your body, its size, type, and any biomarkers that can be used to guide the selection of treatments.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is emotionally difficult. There is a lot of information to take in, and it can be hard to comprehend all at once. If you realize that you didn’t understand everything in your report during the first review, don’t hesitate to ask to review it again. A social worker can also help you through the process.

Learn more about Dana-Farber’s Adult Social Work Program.

Which doctor do I ask about my pathology report?

The most appropriate doctor to talk to varies depending on where you are in the process of diagnosis and treatment.

- If your pathology report details the results of a biopsy to investigate a possible new cancer, the physician who performed your biopsy can help you understand the results.

- If your report provides an analysis after surgery performed to remove cancer, the surgeon who performed the excision can help you understand the results.

- If you have been diagnosed with metastatic cancer and have received a report from a biopsy or removal of metastatic tissue, your medical oncologist will be a good resource.

To avoid confusion, focus on:

- Understanding where you are in the process of diagnosis or treatment.

- Connecting with the right expert who can help you understand your report.

- Making sure you get all your questions answered about your diagnosis and what your care team recommends for next steps.

How do I know if my pathology report is right?

Pathologists often consult with one another to validate their findings before finalizing a report. Large cancer centers like Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center will review findings submitted for a second opinion.

“As part of my job, I do consultations on challenging cases from pathologist all around the world,” says Schnitt.

Learn about Dana-Farber’s Second Opinion Program.

How do I learn more about the details in the pathology report?

Pathology reports typically contain the following detailed sections.

Patient and specimen identifiers

This information includes the patient’s name, birth date, and other personal information. It also details clinical history, the type of biopsy or procedure, and the type of tissue being analyzed.

Some surgical procedures generate multiple specimens that are submitted together to the pathologist. For instance, a colonoscopy might generate multiple specimens. Information about each sample will be labelled so that the clinician knows which location each sample came from.

Gross description

The gross description details the size and appearance of the sample on the outside. This section will also include an index of samples prepared by the pathologist for microscopy.

Microscopic description

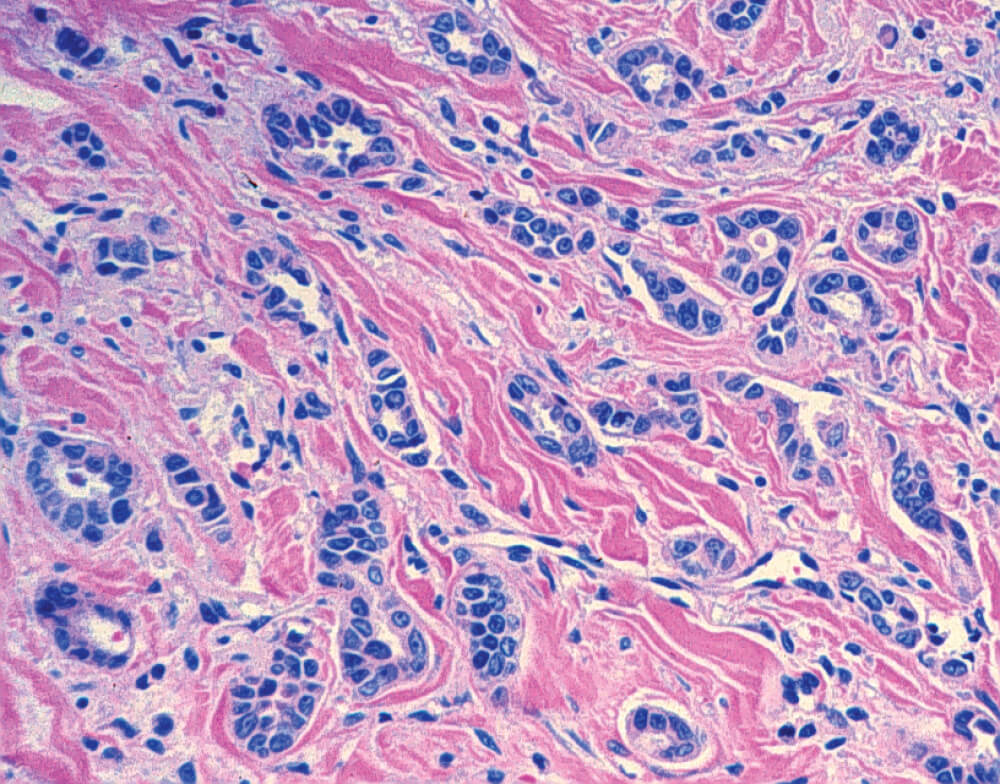

Each sample is sliced, stained, and mounted on a glass slide for a pathologist to examine under a microscope. For surgical specimens involving cancer, pathologists will create a separate report, called a synoptic report, for each specimen examined.

These reports will include details that can help guide treatment options. Details include:

- Histologic type – The type of cancer based on how the cells and tissues look under the microscope. Histologic types can vary even within a given organ.

- Tumor grade – The grade measures how abnormal the cells look. A higher number means the cells are more abnormal.

- Margins – A negative margin means the resected cancer is completely contained within the surgically removed specimen. A positive margin means that the surgeon couldn’t remove all the cancer. Margins aren’t measured when a sample is a biopsy which is a just small piece of the tumor.

- Mitotic rate – This is a measure of how quickly cells are dividing and may give a sense of how quickly the cancer is growing.

- Invasiveness – Your surgeon may have removed lymph nodes or other tissues for inspection to see if the cancer has spread.

- Biomarkers – For certain forms of cancer, samples are studied in ways that highlight cancer cells that have certain flags. Those flags can indicate if a specific type of targeted medicine or immunotherapy might be effective. Some biomarker readouts are supplied later.

Some details in a pathology report might be alarming. Please work with your care team to understand how they can help guide your treatment. There are many different treatment options and clinical trials to consider, and those details, though scary, could be the key to knowing the best next steps.

For some forms of cancer, your doctor might also order genetic testing of the tumor to understand the mutations driving its growth or germline genetic testing to determine if you have inherited cancer risk genes. The results of these tests can help your care team select the best treatment options.

If you need additional support to help you cope with or understand your results, Dana-Farber has programs such as the Patient Navigator Program and the Adult Social Work Program that can help.

About the Medical Reviewer

Stuart J. Schnitt, M.D. is the Chief of Breast Oncologic Pathology for the Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Associate Director of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Brigham and Women’s Hospital Breast Oncology Program, co-leader of the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center Breast Program, Senior Pathologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a Professor of Pathology at Harvard Medical School and an internationally recognized expert in breast pathology. Dr. Schnitt did his internship and residency in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston followed by a fellowship in surgical pathology, also at Beth Israel Hospital. He was a faculty member in the Beth Israel Hospital/Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Department of Pathology from 1984-2017, including 11 years as Director of Anatomic Pathology and subsequently Vice Chair for Anatomic Pathology. He has published over 340 original articles, review articles, editorials, commentaries, and book chapters, primarily in the area of breast diseases. He has authored a popular breast pathology textbook entitled “Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast”, now its third edition. The first two editions of this book were also published in Chinese. In addition, he is one of the editors of the 4th Edition of the “World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Breast”, published in 2012. Dr. Schnitt is a Past President of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology (2010-2011). Other notable honors include the Arthur Purdy Stout Society of Surgical Pathologists Annual Prize (1999), the Albany Medical College Distinguished Alumnus award (2014), the Lynn Sage Distinguished Lecturer (2014) and the Maude Abbot Lecture at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology Annual Meeting (2016). He is particularly proud to have been involved in the training of 35 breast pathology fellows since 1995. He has lectured extensively around the world. His research interests and contributions to our understanding of benign breast diseases and breast cancer have been broad, but have largely focused on risk factors for local recurrence in patients with invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast conserving therapy, benign breast disease and breast cancer risk, and stromal-epithelial interactions in breast tumor progression.

Nicely done! Thank you!