- Predicting who is likely or unlikely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors remains a focus for researchers.

- Tools for predicting responsiveness will need to take multiple factors — clinical information as well as genomic analysis — into account, according to Dana-Farber researchers and others.

For all their potential to curb or even cure some cancers, drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors come with a caveat: They’re effective in only a subset of patients. Predicting who those patients are, and understanding why others don’t respond as well, remains a major challenge.

In a new study, researchers at Dana-Farber in collaboration with investigators in Germany, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Massachusetts General Hospital found that, for patients with metastatic melanoma, a combination of molecular data and clinical information — including whether the patient has received previous treatment with a different checkpoint inhibitor — provides the best forecast of whether a checkpoint inhibitor is likely to be effective.

“Our findings show that while molecular data about the tumor is very powerful by itself, it isn’t sufficient, at this point, for determining which patients will respond to this type of checkpoint inhibitor,” says David Liu, MD, MPH, of Dana-Farber and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the first author of the study, which is being published in Nature Medicine. “Tools for predicting responsiveness will need to take multiple factors — clinical information as well as genomic analysis — into account.”

The findings are based on data from the largest group of patients yet studied who had metastatic melanoma, were treated with drugs known as PD-1 inhibitors, had their tumor tissue analyzed for molecular abnormalities, and had the results linked to information on the course of their disease.

Clues to new drug targets

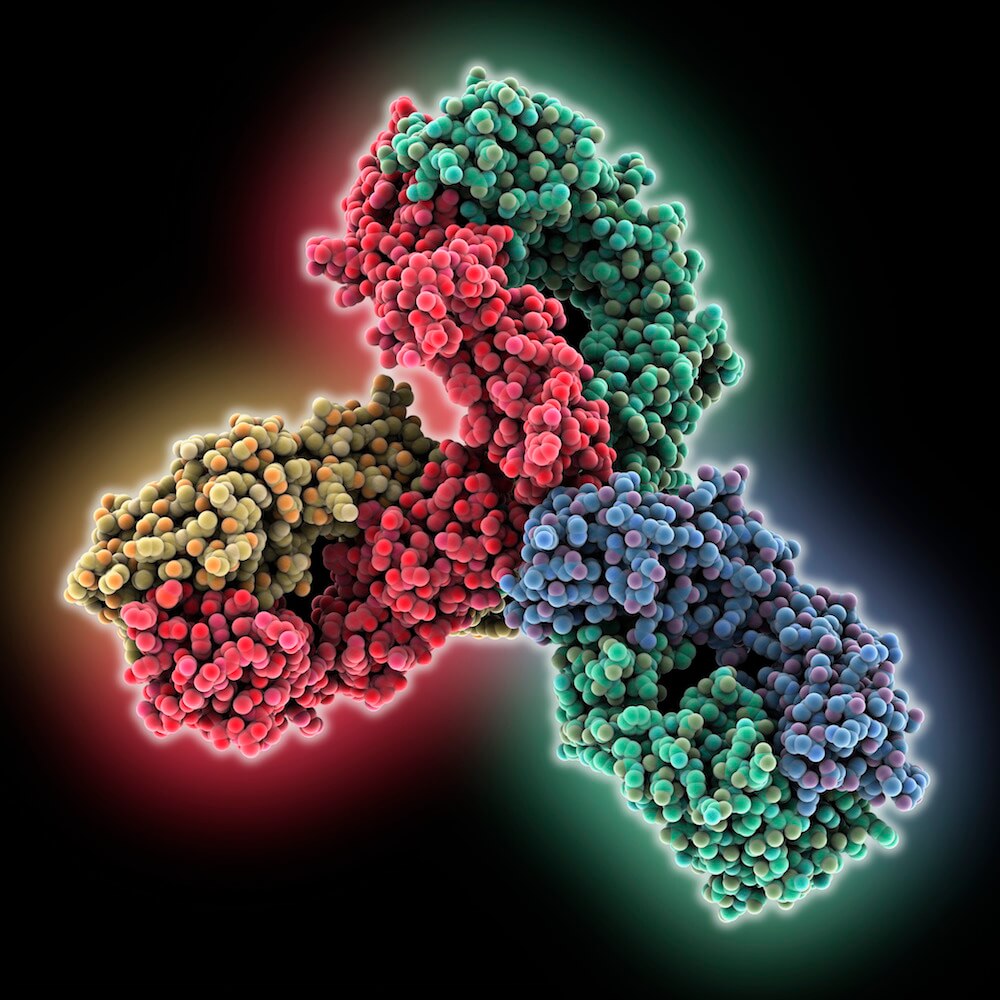

The target of the drugs is PD-1, a protein on immune system T cells that links up with a tumor cell protein to stop a T cell attack on cancer. By preventing these proteins from joining, PD-1 inhibitors allow the attack to proceed. Checkpoint inhibitors have produced dramatic, long-lasting results in some patients with melanoma, kidney, bladder, lung, head and neck, and other cancers, and are currently being tested in clinical trials in more than 30 cancer types. For the most part, however, the drugs have benefitted only a modest percentage of patients, underscoring the need to determine, in advance, who those patients are.

“Having this information could provide us with clues to new drug targets for patients who aren’t helped by checkpoint inhibitors,” Liu says. “Until such drugs are developed, patients in this situation might be treated by other targeted therapies, more intensive therapy, or clinical trials of new agents.”

Researchers analyzed tumor tissue from 144 patients with metastatic melanoma, looking for changes in cell DNA as well as gene expression (the turning up or down of specific genes). These data were correlated with information on patients’ response, or lack of response, to PD-1 inhibitors.

The investigators found that an aspect of patients’ medical history — previous treatment with checkpoint inhibitors called CTLA-4 blockers — was important to predict whether they’d respond to PD-1 inhibitors. If patients had already undergone this treatment, and their tumor tissue showed no signs of immune system activity, they were very unlikely to respond to a PD-1 inhibitor. If they hadn’t received a CTLA-4 blocker, the presence or absence of immune system activity within the tissue had no bearing on whether a PD-1 inhibitor would be effective.

Patients who had previously been treated with a CTLA-4 blocker tended to respond better to PD-1 inhibitors if their tumor cells had an oversupply of MHC-II molecules (which display key proteins to the immune system), had low LDH (a lab test associated with how much cancer a patient has), or had cancer in the lymph nodes. Patients without prior CTLA-4 blocker treatment were less likely to respond if their tumors were highly heterogeneous (made up of many genomically distinct cell groups), had a high degree of “purity” (dense tumors without many other types of cells), or had lower ploidy (changes in tumor DNA that result in less overall DNA).

The “mutational burden” of the tumor cells — the number of genetic mutations they carried — was an imperfect indicator of PD-1 inhibitor response, researchers found. Patients who responded to a PD-1 inhibitor with one type of melanoma had a lower mutational burden than patients who didn’t respond to a PD-1 inhibitor with a different type melanoma.

“Our results highlight the value of integrating clinical data with molecular data in understanding which patients are likely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors, and why,” Liu remarks, adding that future research will seek to verify these findings in prospective studies of larger groups of patients.

Eliezer Van Allen, MD, of Dana-Farber and Dirk Schadendorf, MD, of University Hospital, Essen, Germany, are senior authors, and Bastian Schilling, MD, of University Hospital, Wurzburg, Germany, co-led the study.