When Dana-Farber launched its new Center for BRCA and Related Genes in August 2020, it was with patients like Janice Dolnick in mind. Dolnick’s cancer journey had already been a long one before she came to Dana-Farber for a consult in 2018. Over the previous 21 years, she’d been through two rounds of breast cancer treatment and a bilateral mastectomy. She knew that her BRCA1 mutation put her at much greater risk for ovarian cancer, from which her mother and a cousin had died. So she’d also had both of her ovaries removed in a procedure called a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

But in 2018, Dolnick just wasn’t feeling like herself. An ultrasound revealed that she had primary peritoneal cancer, which affects the cells lining the abdominal cavity.

“I was in complete shock,” she says. “I knew I needed to find a place that treats a lot of patients with this kind of cancer. Dana Farber is on the cutting edge of research so I felt that they would know the best course of treatment for someone in my situation.”

‘I knew immediately I was in the right place’

Dolnick felt at ease from her first visit with Panos Konstantinopoulos, MD, PhD, director of translational research in Gynecologic Oncology at Dana-Farber’s Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers and the director of the Center for BRCA and Related Genes.

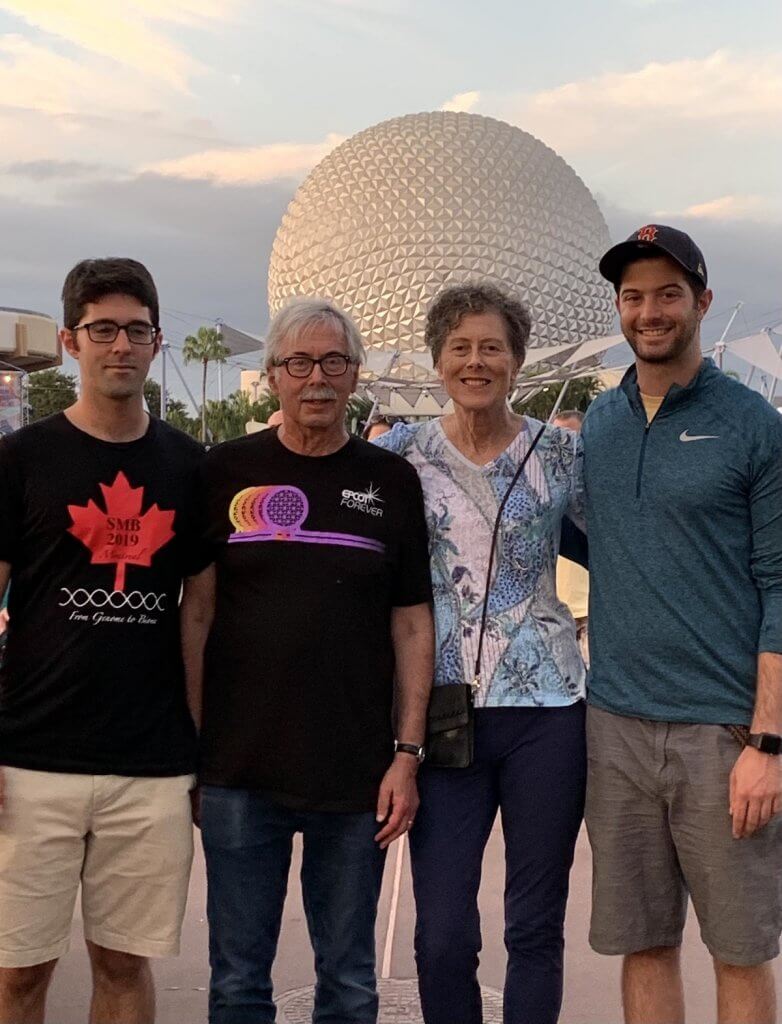

“I knew immediately I was in the right place and being treated by the right person,” Dolnick says. “Dr. K gave me the confidence to believe I would be able to celebrate many more milestones with my husband and twin sons, now 27.”

Konstantinopoulos put her on a regimen of intraperitoneal chemotherapy, which delivers chemo directly to the abdomen. It was an aggressive way to treat the cancer, so Dolnick was grateful for the support of her husband, Joe, and sons, Alex and Daniel.

Once Dolnick went into remission after chemotherapy,Konstantinopoulos started her on PARP inhibitors, which prevent the repair of cancer cells in the body and can slow the return or progression of cancer.

“There’s a 70 percent reduction in risk of the disease coming back or dying from the disease,” he says. “That’s a very big improvement for patients with the BRCA mutation.”

Dolnick suffered a rare side effect called pneumonitis on one PARP inhibitor, so she switched to another one called niraparib, which had just been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. She was among the first patients to receive it.

‘I’ve hit the point where I don’t think about the cancer all the time’

Three years later, Dolnick has completed her treatment with the PARP inhibitor and remains cancer-free. She is back to her active life style including exercise, biking and traveling, volunteers at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and uses her marketing and consulting skills to help nonprofits through Empower Success Corps.

“She has done amazingly well,”Konstantinopoulos says.

Dolnick feels fortunate to have celebrated 32 years of marriage, see one son get married and another obtain his dream job. She and her husband recently moved to Back Bay to be able to take greater advantage of all that the city has to offer.

“I’ve hit the point where I don’t think about the cancer all the time,” she says. “That’s because Dr. Konstantinopoulos has made me realize there is a growing toolbox of different treatments that is always evolving. He always says if it comes back, we’ll just try something new.”

That’s the philosophy behind the Center for BRCA and Related Genes, which is dedicated to the care for, prevention of, and research into BRCA-related cancers. Teams of specialists at the Center work closely together to offer patients the latest therapies and clinical services. They place high priority on providing access to innovative clinical trials and novel therapies, with a particular focus on overcoming developed resistance to chemotherapy, targeted agents and DNA repair inhibitors — such as the PARP inhibitors that have proven so successful for Dolnick.

“I want people to have a sense of optimism, that they can go through this and lead very full lives and have a lot to look forward to,” Dolnick says. “There are more treatments and more ways to prevent the disease being developed every day, thanks to places like Dana-Farber.”