The results of the phase 2 clinical trial would have been impressive even if they didn’t involve a particularly stubborn form of cancer.

In the trial, led by Dana-Farber’s Jonathan Schoenfeld, MD, MPH, 29 patients with locally advanced squamous cell cancer of the oral cavity were treated with one or two immune checkpoint inhibitors — drugs that lower cancer cells’ defenses against an immune system attack — followed by surgery to remove any remaining tumor tissue. More than half of them had their tumors shrink following immunotherapy treatment; four had more than 90% of their tumor cells die within two to three weeks. Three years after study enrollment, more than 86% of the participants were alive – numbers significantly better than those achieved by standard therapy.

Although the trial was relatively small and will need to be corroborated by larger studies, the results inspired Dana-Farber’s Kai Wucherpfennig, MD, PhD, and his colleagues to scrutinize the immune system T cells that made these results possible. Their findings, published in a study in the journal Cell, depict an immune system that responds with alacrity and agility to treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. The response is supple enough that it not only targets malignant cells within the tumor but also is ready for them if they escape into the bloodstream.

The findings will also help physicians identify patients with this type of oral cancer who are most likely to benefit from the treatment.

“This clinical trial presented a unique opportunity to explore the effects of checkpoint inhibition on T cells — which form the backbone of the immune system’s response to cancer,” says Wucherpfennig, who led the study with Schoenfeld and postdoctoral fellows Adrienne Luoma, PhD, and Shengbao Suo, PhD. “We found that treatment with checkpoint inhibitors triggered a rapid and sharp increase in certain sets of T cells in both the tumor and the circulation.”

Doing double duty

Checkpoint inhibitors are often portrayed as rather one-dimensional drugs. They work by targeting proteins that help cancer cells stave off an immune system attack. But they do more than strip cancer cells of a layer of protection: they also can activate, or switch on, cancer-fighting T cells.

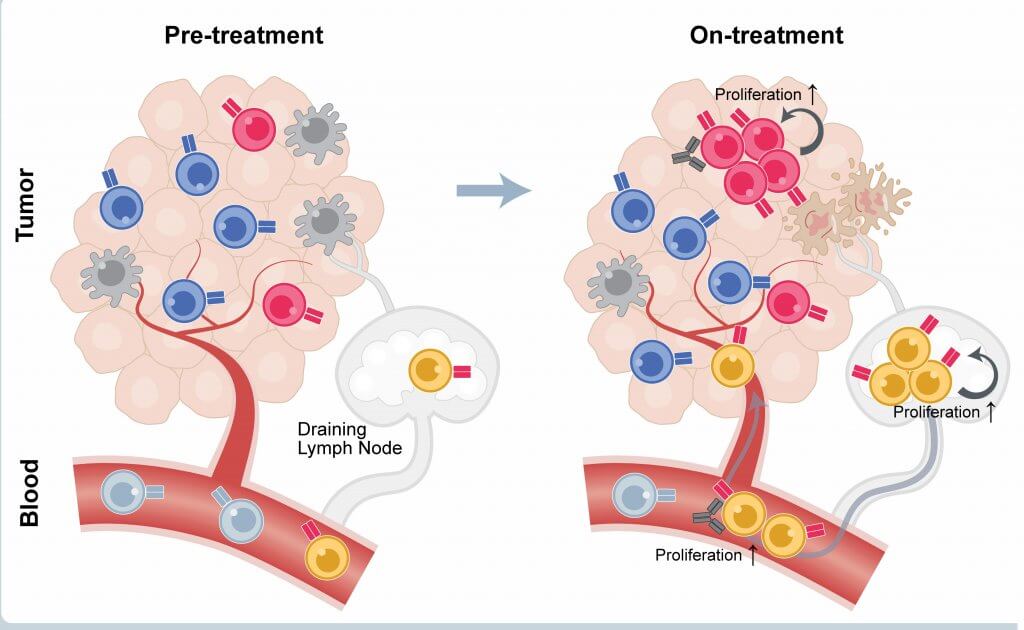

In the current study, researchers studied the effect of checkpoint inhibitors on T cells in patients who benefited from the drugs in the clinical trial. They focused on two, closely related groups of T cells: those within patients’ blood and those within the tumor tissue itself.

When researchers examined blood and tumor samples taken shortly after treatment, they saw a T cell population boom. “When T cells are activated, they proliferate,” Wucherpfennig explains.

But researchers were interested in more than numbers: they wanted to know which specific subpopulations of T cells had grown the most. They found that, in tumor tissue, these cells had a distinct molecular program — a particular set of switched-on genes.

The program, known as the tissue-resident memory (or Trm) program, is particularly important in the immune system’s response to viral infection. “When infection occurs, T cells go to the affected tissue to fight the virus,” Wucherpfennig relates. “Trm allows the cells to persist in tissue for years; so, if there’s a reinfection, the immune system can respond promptly. The T cells in the tumors we studied had the same program. We think these are the cells that sprang into action when patients received checkpoint inhibitors.”

The blood of patients who responded to checkpoint inhibitors also showed a surge in certain T cells. Patients who, prior to treatment, had large numbers of CD8 T cells (also known as killer T cells) that tested positive for the PD-1 protein but negative for the KLRG1 protein tended to have the best responses to the inhibitors. Such cells can be a biomarker to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from the treatment.

“Our findings suggest that treatment with checkpoint inhibitors elicits a strong “local” immune response within the tumor that sets up a secondary systemic response in the blood,” Wucherpfennig observes. “That system-wide response can potentially provide long-term protection against metastatic tumor cells.”