Discovered only about a decade ago, a key actor in the immune system called STING has become a hot target of research aimed at improving cancer immunotherapy. STING (stimulator of interferon genes) has been called a “master regulator” of the innate immune response against cancer. When activated by substances called agonists, STING turns on genes that make interferons — proteins that help the immune system fight infections and cancer.

STING agonists are being tested for their potential to boost the anti-cancer immune response. But these agonists, which worked in the laboratory or in mice, have failed to have much success in humans.

“There’s a big disconnect between what happens in mice and what happens in people,” says David Barbie, MD, a physician-scientist in the Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology at Dana-Farber.

Barbie and a number of collaborators recently published a study that used human tumor samples — patient-derived organotypic tumor spheroids, or PDOTs — to assess the effects of STING agonists on tumor cells and different types of cells in the human microenvironment. They used PDOTs made from samples of malignant pleural mesothelioma — cancers that develop in the layer of tissue covering the lungs and chest wall. The PDOTs are small microenvironments of tumor cells; the researchers also used larger fragments of mesothelioma tumors taken during surgery on patients.

“We said, let’s treat these human mesothelioma tumors with STING agonists to see how they act on the tumor microenvironment,” says Barbie. They found that the tumor cells were highly responsive, and the agonists upregulated interferon and recruited T cells into the tumor microenvironment — but the agonists killed the T cells, rendering them useless to fight the cancer.

This experiment with the human organoids showed that STING agonists are toxic to T cells. “This was an unexpected finding,” adds Mubin Tarannum, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher and an author of the study. The scientists say this finding “could contribute to the disappointing clinical activity of STING agonists to date in humans.”

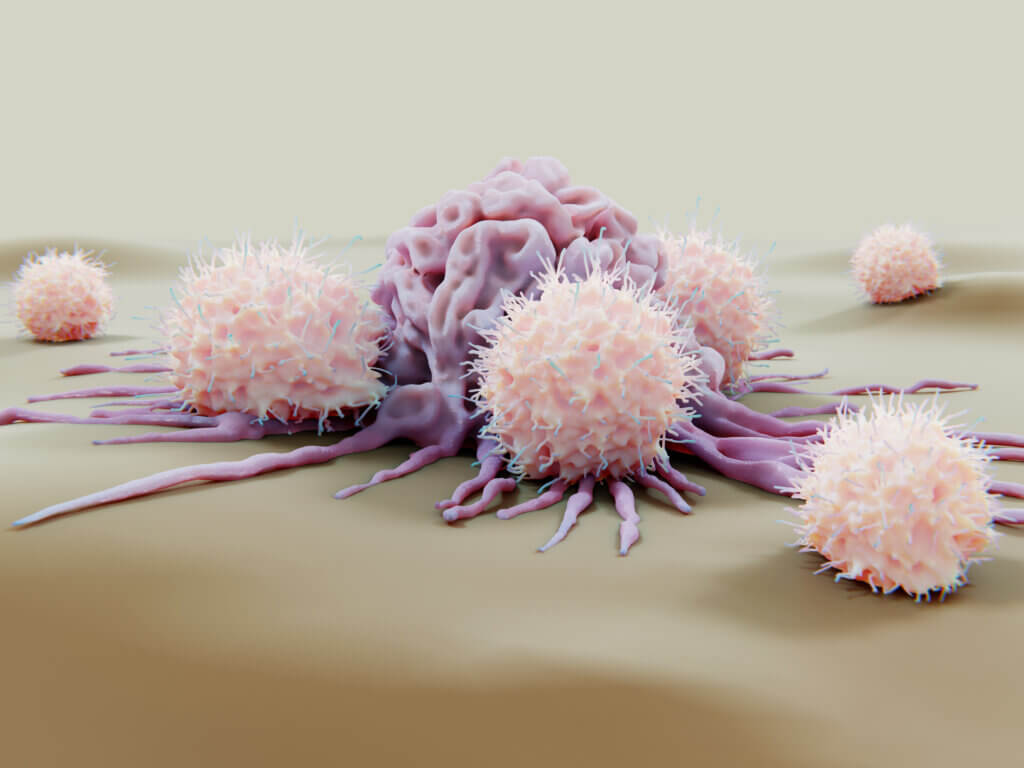

However, by contrast, natural killer (NK) cells — immune cells that are first responders to infections or cancer cells — did not succumb to the STING agonist. In fact, the NK cells’ response against the tumor cells was enhanced by the STING agonists, improving their therapeutic activity, the scientists say.

Consequently, they say, the studies reveal that the limitations of STING agonist treatment can be overcome by the addition of NK-cell therapies, which enhance NK-cell migration into the tumor microenvironment and killing of tumor cells. This suggests that a way forward with STING agonist cancer treatment may be “a combinatorial approach with NK-cell therapies to develop clinically.” Another takeaway from the study, the scientists emphasize, is that testing STING agonists in human tumor samples has important advantages over testing in mouse models.

Other authors of the study include Raphael Bueno, MD, Chief of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Division of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery, Cloud Paweletz, PhD, of the Belfer Institute for Applied Cancer Science at Dana-Farber, and Rizwan Romee, MD.