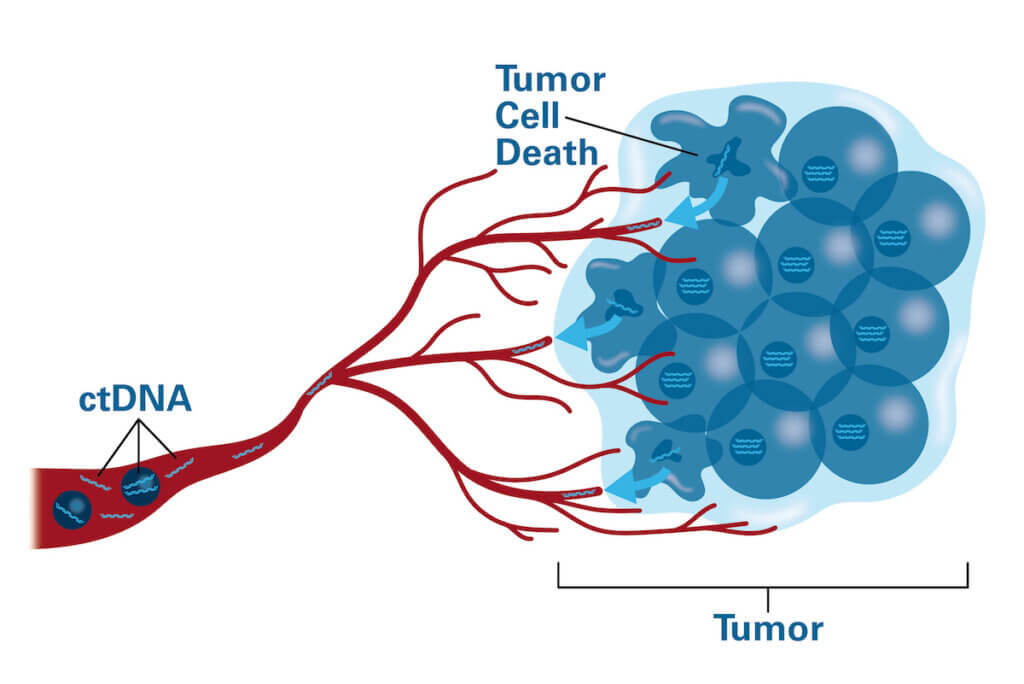

Like a mill crumbling into a river, solid tumors constantly shed bits of themselves — including their DNA — into the bloodstream. This free-floating genetic material, known as circulating tumor DNA, or ctDNA, contains a trove of information about the tumor.

Advances in technology have made it possible to extract ctDNA from a blood sample, measure it, and analyze it for genetic abnormalities. These tests, known as liquid biopsies, are being studied for their potential in guiding cancer care.

How does ctDNA get into the bloodstream?

Although cancer cells are said to be “immortalized” because they often defy signals ordering them to die, they can die of other causes — sometimes because they are so deep within a growing tumor that they lose access to nutrients carried by the blood. When they die, they disintegrate, spilling their contents, which ultimately wind up in the bloodstream. Live tumor cells also can secrete DNA as part of their normal functioning.

How might ctDNA testing be used?

Researchers and physicians see numerous potential roles for ctDNA testing:

- Detecting cancer early: The presence of ctDNA in an individual’s blood may allow doctors to detect certain types of cancer before symptoms appear or before other tests are capable of finding it. “In many types of cancer, including pancreatic cancer, we don’t have reliable ways of detecting tumors in their earliest stages, or monitor them after treatment,” Dana-Farber’s Heather Parsons, MD, MPH, notes. “Liquid biopsies may help fill that gap.”

- Selecting treatment: By analyzing ctDNA for specific genetic mutations, liquid biopsies may help physicians choose therapies that are effective against cancers with those particular abnormalities. ctDNA tests might also help doctors determine which patients require intensive treatments and which can do just as well with less intense approaches.

- Assessing treatment effectiveness: Studies have consistently shown a connection between ctDNA levels and tumor status: when tumors shrink or disappear, ctDNA levels often decline. Monitoring ctDNA levels during and following treatment may offer a way to gauge how well therapy is working.

- Detecting relapse: Just as a drop in ctDNA counts can indicate that a treatment is effective, a rebound in ctDNA levels may be a sign that a cancer has returned, despite treatment intended to cure it, or that it has resumed its growth, in the case of advanced cancer.

- Tracking changes in tumors’ genetic signature: As tumors grow and evolve, they often acquire new mutations and other genetic abnormalities. Periodic liquid biopsies can reveal these changes as they emerge. Such mutations may represent vulnerabilities within the tumor that can be attacked with targeted therapies. They may also indicate that a tumor is developing resistance and guide a change in treatment.

What are the potential advantages of a liquid biopsy using ctDNA?

Because ctDNA is carried by the blood, liquid biopsies can be performed with a simple blood draw. Tissue biopsies, by contrast, involve inserting a needle directly into the affected tissue and removing a small sample for examination. Liquid biopsies are especially useful for monitoring or tracking a patient’s response to treatment over time: it’s far easier and less invasive to periodically collect blood samples than tissue samples.

Liquid biopsies may capture ctDNA released by cancer cells no matter where those cells are within a tumor. Because tissue biopsies usually collect samples from several specific sites in an organ or tissue, they may miss genetically distinct subgroups of cancer cells in other sites.

How are liquid biopsies currently used in the clinic?

Technology for quantifying and analyzing the ctDNA in a blood sample is relatively new, and much remains to be learned about how best to apply it to patient care. For some cancer types, such as breast and lung tumors, it has become standard practice to use liquid biopsies as part of a diagnostic workup.

At the Dana-Farber/Brigham Cancer Center, for example, patients with metastatic breast cancer receive ctDNA testing to determine whether their tumor cells are likely to respond to specific targeted drugs. “We draw blood for testing at the time of their diagnosis and periodically afterwards — if their disease is advancing — to look for potential targets for therapy or signs of drug resistance,” Parsons says.

Researchers are examining the value of liquid biopsies in a variety of other tumor types. Many of these studies seek to establish consistent guidelines for interpreting liquid biopsy results: what do ctDNA levels indicate about a tumor’s response to therapy or its potential to relapse or metastasize? How much of a decrease is a sure sign of tumor shrinkage? How much of an increase suggests relapse or metastasis?

“The accuracy of liquid biopsies is high: they produce extremely precise readings of ctDNA levels and genetic mutations,” says Dana-Farber’s Brian Crompton, MD, of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. “The goal now is to demonstrate that certain ctDNA levels are definitively prognostic — that they can provide reliable information about the tumor’s status, which can be used in making treatment decisions.”

In some cases, liquid biopsies are becoming part of standard care.

What research is being done in ctDNA?

Research at Dana-Farber was critical in demonstrating the ctDNA could be the basis of a practical clinical test. One of the challenges of analyzing ctDNA is determining how much of the ctDNA in a blood sample comes from tumor cells and how much from normal cells. Parsons and other researchers devised a method called “tumor fraction” that makes this ratio easy to calculate. In a follow-up study, she and her colleagues used the technique to show that a high tumor fraction is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with metastatic, triple-negative breast cancer.

Dana-Farber researchers have published numerous studies evaluating the potential of ctDNA liquid biopsies for diagnosing, tracking, and predicting the behavior of cancer. Among them:

- The CHiRP study, led by Parsons and Dana-Farber’s Marla Lipsyc-Sharf, MD, found that, in women diagnosed at least five years earlier with early-stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, a ctDNA blood test can often identify those with a high risk of cancer recurrence.

- A study, also led by Parsons, showed that, in women with triple-negative breast cancer receiving chemotherapy after surgery, ctDNA levels dropped far more sharply in patients who responded to the chemotherapy than in those who did not.

- Work by Crompton and his associates has been critical to adapting ctDNA testing to pediatric patients. Because the patterns of genetic abnormalities in pediatric tumors often vary widely from those in adult cancers, the ctDNA tests used for adults are often not applicable to young patients. Crompton’s team developed simplified methods of blood sampling for use in pediatric patients.

- A study by Crompton and his associates showed that ctDNA can be detected and measured in patients with any of the five most common solid tumors in children: Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms tumor.

- Research by Elizabeth Stover, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the Ohio State University showed that frequent ctDNA tests of patients with metastatic cancer are a useful way of tracking the changing genomic features of the cancer. Stover also is conducting a study to evaluate the changes in ctDNA over time in patients with ovarian cancer being treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery.

- A study by Jacob Sands, MD, found that in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, genomic testing by ctDNA can be cost-effective.