Allison Schablein seems an unlikely candidate to teach medicine to Mark Kieran. She’s an 8–year-old New Hampshire second grader who loves basketball, hip hop, acrobatic dancing and jewelry. He’s a pediatric neuro-oncologist with a PhD in molecular biology, not to mention decades of clinical and research experience. But teach Kieran, Allison does.

In December 2012, Allison was diagnosed with metastatic anaplastic astrocytoma brain tumors – two on her brain stem, two on her spine, and three at the top of her head. She had surgery and chemotherapy – and for two months her tumors responded to therapy. Then treatment stopped working.

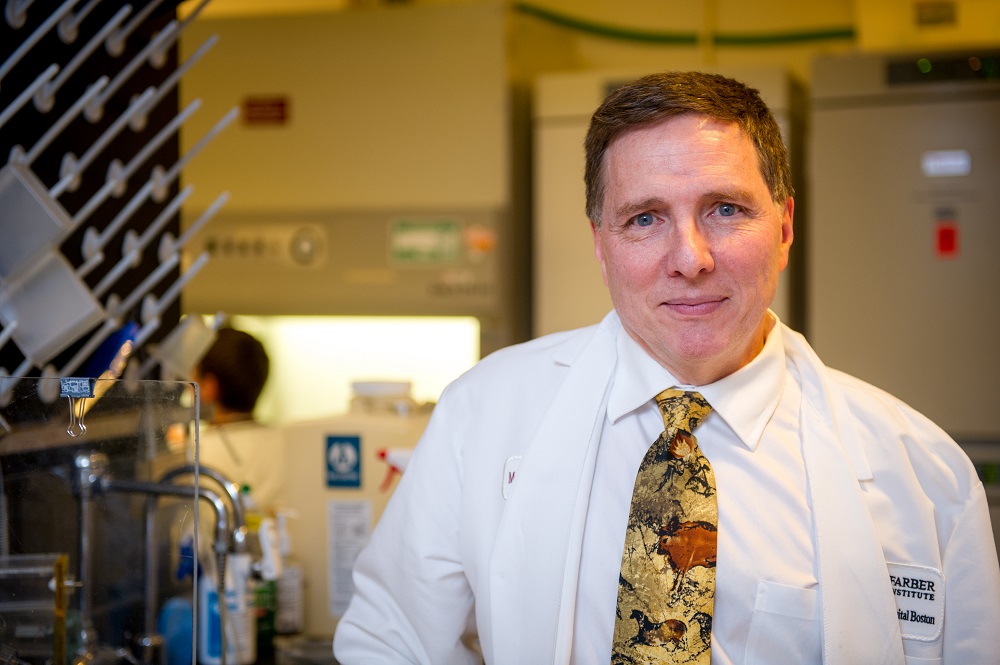

Genomic testing revealed Allison’s tumors had a genetic mutation – a so-called BRAF mutation — seen in some cases of melanoma, a skin cancer that mostly affects adults. Kieran, clinical director of the Brain Tumor Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, suggested enrolling Allison on a clinical trial of dabrafenib, a drug targeting the BRAF mutation in melanoma patients. She would be the first pediatric brain tumor patient in the world to join the trial.

Within two months, Allison’s tumors were gone – or, at least, had shrunk so much they were no longer visible on an MRI. By honing in on the BRAF mutation associated with Allison’s cancer, the precision medicine had successfully attacked her tumors. This is the cutting edge of pediatric cancer treatment, with new research showing that precision medicine is extending its reach from adults with cancer to children with cancer.

Read more:

“For us to be where we are now is incredible,” says Dan Schablein, Allison’s father. “But with her being the first, they don’t have answers to any of our questions. She’s giving the answers.”

“Allison is a pioneer, Kieran says. “When she was born, we knew virtually nothing about malignant gliomas in children, including anything about the BRAF mutation. In less than five years, we were able to translate that finding into an effective therapy for this remarkable girl. We are now on the hunt for different mutations in other types of brain tumors, and the drugs that can target them.”

Every three months, Allison and her parents return to Boston for an MRI to see if the girl’s tumors have returned. “Every time, it’s nerve wracking,” Schablein says. “Going to sleep the night before is impossible.”

Every year, Schablein and his wife, Michelle Moscardini, in consultation with Kieran, face a difficult decision. Will they continue giving their daughter the drug? Or will they stop and hope the impact persists? They keep Allison on the medication. “We don’t like giving a kid drugs,” Schablein says. “On the other hand, we know what the alternative could be.”

In addition to teaching Kieran, Allison is also teaching her parents.

“She was so happy from start to finish,” Moscardini says. “She understood, and she’s taught us a lot. We’d be upset, and she’d say, ‘Mommy, don’t be upset. I’m going to be OK.’”

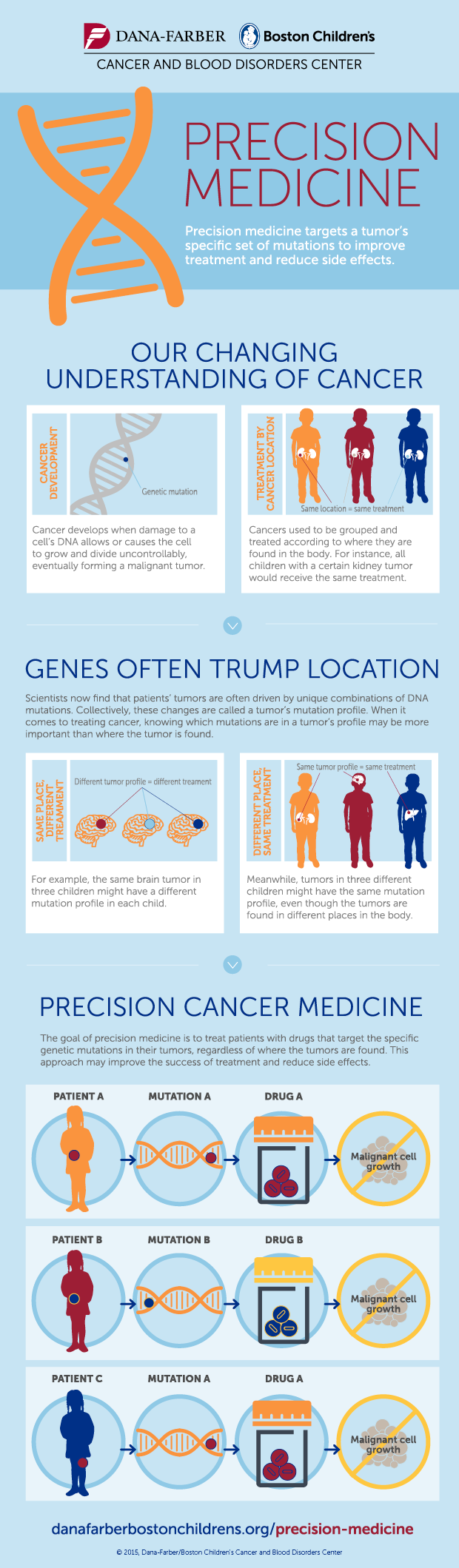

Learn more about precision medicine in the infographic below: