In their Brookline home-far-away-from-home, 2-year-old Duy Anh “Harry” Le plays with blocks and pop-up toys on the floor with his mother, Thao Nguyen. He is lively and happy, and his skin is clear. He looks almost nothing like the sickly baby covered in eczema who arrived in Boston from his native Vietnam in November 2016 to participate in a gene therapy clinical trial for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Children with the potentially life-threatening, inherited immune system deficiency have difficulty producing platelets, the blood component that fosters clotting, which leaves them susceptible to bleeding. Their compromised immune systems leave them susceptible to infections, eczema, autoimmunity and cancer. The disorder is so rare that Harry’s physician father, Duy Le, an adult ear, nose and throat specialist, had not heard of it. It is so rare that many doctors have trouble diagnosing it.

When Harry, at two months, exhibited bleeding spots on his legs, doctors in Vietnam suspected dengue fever. Then the baby developed eczema and pneumonia-like infections, so physicians treated him for an autoimmune disorder for four months. Finally, at the age of six months, Harry was diagnosed with WAS. He needed a stem cell transplant, but Vietnam has little experience with pediatric transplants and Harry didn’t have a matched donor.

Learn More:

“The first few months after the diagnosis we felt no hope,” Le recalls. “We were despondent. Scared about Harry’s future.”

Duy scoured the Internet and learned about the gene therapy trial for WAS at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Meanwhile, Harry was suffering infections. He had lesions due to inflamed blood vessels in his mouth, which made it so difficult to eat he was underweight and could only consume liquids. He was scratching his eczema sores and having trouble sleeping because of pain. “Sometimes we had to hold him the whole night,” his mother says.

When the family arrived in Boston from Ho Chi Minh City, Harry’s platelet count was 28,000, well below the 50,000 count considered sufficient to engage safely in normal activities. In Vietnam, his platelet count had gotten as low as 5,000.

“Leaving home is really hard,” Le says. “But he’s our only child. We didn’t have to think.”

Doctors collected Harry’s blood stem cells and used a specially designed virus they had engineered in the laboratory to insert a correct version of the defective gene into the boy’s stem cells. Meanwhile, Harry underwent chemotherapy to destroy his diseased bone marrow and make room for new, healthy cells. On January 27, clinicians infused the corrected cells into Harry’s bloodstream via an intravenous line. Because gene therapy uses a patient’s own cells, there is no risk of graft-versus-host disease, which occurs when the donor’s grafted cells react against the host patient’s cells.

For the next six months, while the corrected cells engrafted and Harry’s immune system grew stronger, the family lived in Boston House, which offers housing for Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s patients. When the Les left Boston August 10 to return to Ho Chi Minh City, Harry’s platelet count was 91,000, well above the threshold that clears him to participate in all activities with no greater risk than other children.

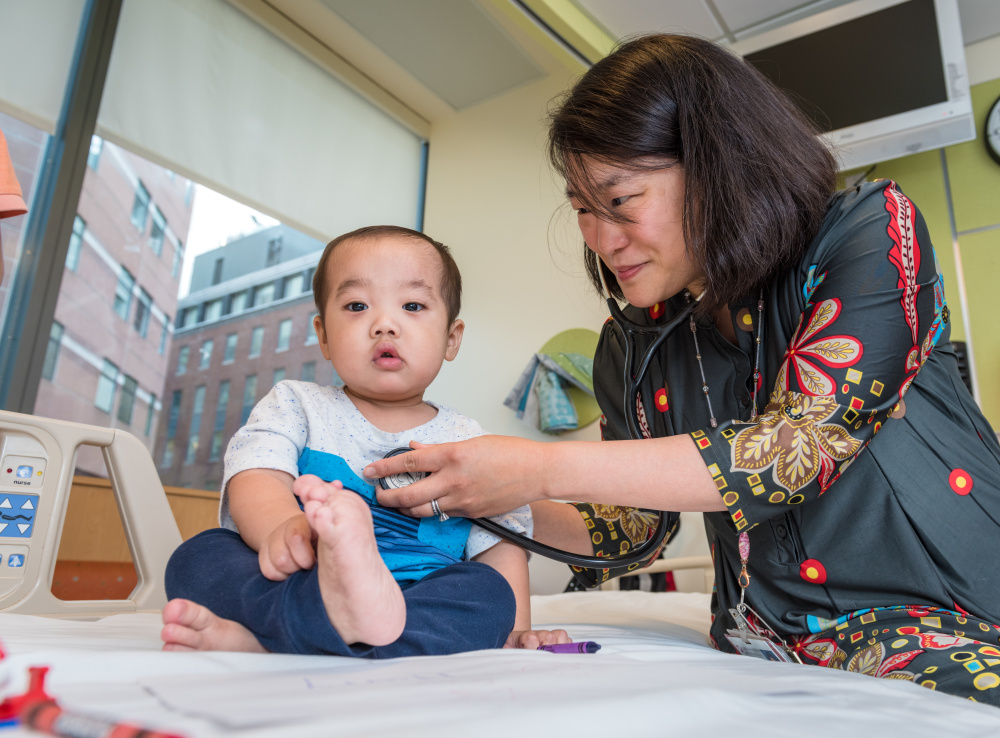

“Harry is doing great. He’s gained weight. He can eat. He’s walking. He’s talking. He’s just developed and blossomed,” says Sung-Yun Pai, MD, his Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s pediatric hematologist/oncologist and principal investigator of the trial, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Gene Therapy Resource Program. “He was extremely sick when he first came. His parents were desperate. Seeing him grow and thrive is one of the best things about my job.”

Harry will be monitored for the next 15 years, starting with annual trips to Boston for the next five years, followed by a decade of bloodwork and other clinical data sent from Vietnam to Boston.

“I always say a miracle happened with gene therapy,” Le says, “and Harry was born again in Boston.”