At its most basic level, gene therapy is a powerful technique for correcting mistakes (called mutations) in DNA of human cells. Lately, the therapy has been gaining traction as a potentially life-saving treatment for children with an array of inherited rare blood and immune disorders, as well as certain cancers.

Gene therapies are being carefully tested in clinical trials, using improved, safer DNA delivery methods to reduce the risk of complications: some patients in earlier trials developed leukemia when treated with previous “vectors” – engineered viruses that transfer copies of normally functioning genes into cells of ill patients. So far, the improved vectors have been associated with fewer complications.

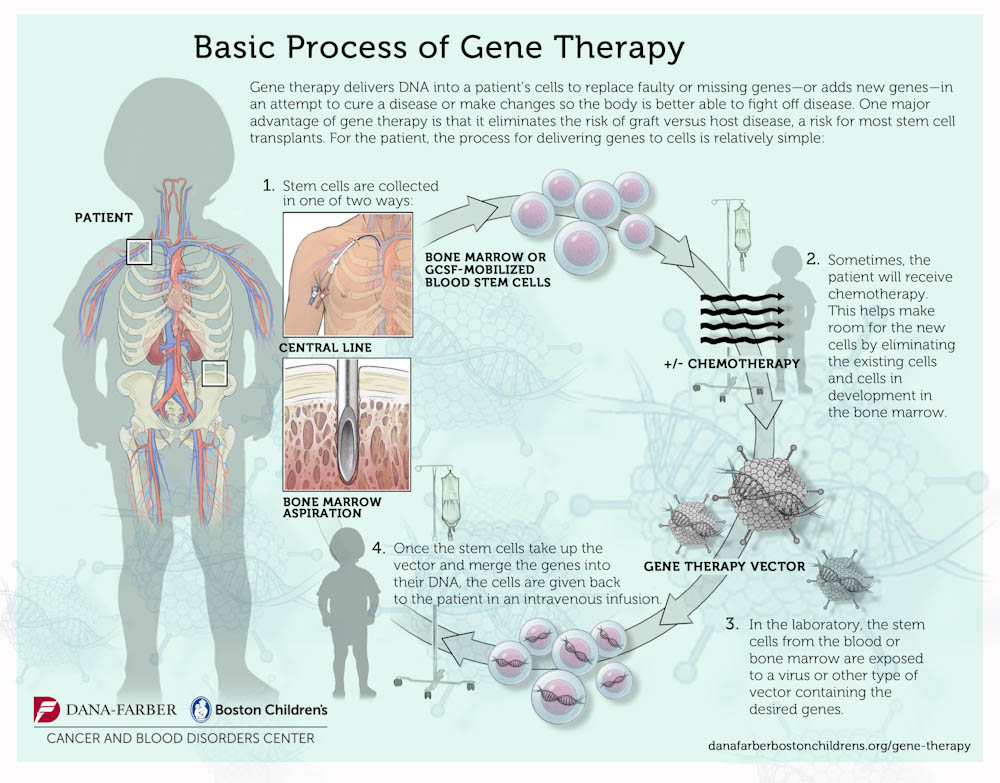

One example of the use of gene therapy is in immune deficiencies. Because they have inherited a defective gene, children born with these immune disorders generally lack a vital protein needed for their bodies to develop a robust assortment of immune defender cells to protect against infections. To correct these often-fatal conditions, scientists modify viruses – rendering them incapable of harmful infection — to ferry normal copies of the gene into blood stem cells removed from the patient; those cells are then re-infused and, if successful, the gene directs the body to make the missing protein.

One example of the use of gene therapy is in immune deficiencies. Because they have inherited a defective gene, children born with these immune disorders generally lack a vital protein needed for their bodies to develop a robust assortment of immune defender cells to protect against infections. To correct these often-fatal conditions, scientists modify viruses – rendering them incapable of harmful infection — to ferry normal copies of the gene into blood stem cells removed from the patient; those cells are then re-infused and, if successful, the gene directs the body to make the missing protein.

Led by David A. Williams, MD, physician-scientists at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center are treating 23 young patients from 17 countries in clinical trials for six different life-threatening medical conditions. Williams is chief of hematology-oncology and director of clinical and translational research at Boston Children’s and associate chair of pediatric oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Four of these trials involve the inherited genetic disorders adrenoleukodystrophy, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) or “bubble boy” disease, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and chronic granulomatous disease.

Read more:

Another new trial is testing a gene therapy technique aimed at reducing graft-versus-host disease in patients who have received a stem cell transplant from a donor who is only a 50 percent genetic match. These donors are usually a parent, making extended searches for donor unnecessary. A common complication of transplants, graft-versus-host disease is a mistaken attack on the recipient’s normal body tissues by the transplanted immune cells. The sixth clinical trial involves an exciting new immunotherapy for cancer, known as CAR T-cells, in patients with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common type of pediatric cancer. Gene therapy plays an important role in this experimental treatment.

In treating cancer, CAR T-cells don’t replace a missing gene; instead, they are a new method for helping the patient’s immune system attack the cancer. The patient’s immune soldiers, T- cells, are removed from the body and genetically modified to produce a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). Returned to the patient, the CARs rally the T-cells and focus their attack on leukemia cells carrying a distinctive protein on their surface.

This method has had some dramatic outcomes in early clinical trials. “We are very excited to test this treatment in children and adolescents with ALL,” says Lewis Silverman, MD, who is leading the trial locally. He is clinical director of the Hematologic Malignancies Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s. By early August, four patients had been enrolled in the trial and their T-cells had been collected.

The gene therapy trials at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s has attracted families and their children from around the world. One of the earliest patients, Agustin Caceres of Buenos Aires, was treated as an infant for SCID-X1. An older sibling had died from the condition, and Agustin’s immune defenses were so weak that extraordinary protective measures were necessary to prevent infection. After a successful treatment in October 2014, his tests show his body is now making normal levels of T- lymphocytes, so his immune system is in good shape.

Emir Seyrek, from Turkey, was the first to be treated in the trial of gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, a genetic immune deficiency affecting boys that causes susceptibility to infections, bleeding and eczema. Typically, Emir’s body was drastically low in platelets – the cells responsible for blood clotting.

In 2013 the two-year-old spent seven weeks at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s, during which his stem cells were treated with a vector carrying a normal copy of the Wiskott-Aldrich gene. Following the gene therapy, his platelet county began to rise – and then soar.

A recent checkup showed that his platelet count, which was 29,000 and lower before treatment, has risen to 148,000.

Sung-Yun Pai, MD, the hematologist-oncologist who leads the Wiskott-Aldrich clinical trial, said, “His immune function is excellent, and we have no worries whatsoever from a bleeding standpoint. He’s perfectly safe to play like a normal child.”

Gene therapy research will expand under the leadership of Alessandra Biffi, MD, who this fall will assume the positions of director of the Gene Therapy Program and director of the Program for Cell and Gene Therapy in Rare Diseases in the Department of Medicine at Boston Children’s. The gene therapy program will be located at Dana-Farber. Biffi has been an internationally known gene therapy research leader in Milan, Italy.

Williams says Biffi will extend gene therapy treatments to new disease targets, including metabolic diseases of children. “This will offer new hope for cure to families with children suffering from these terrible conditions.”