A biomarker—short for “biological marker”—is something that can be objectively measured and is a sign of a normal or abnormal process, or a condition or disease. A biomarker can be a molecule found in the blood or other body fluids or tissues. Another type of biomarker is a genetic signature or “fingerprint”—a pattern of activity in a set of genes that reveals some biological condition.

Examples of biomarkers include everything from pulse and blood pressure to basic chemistries to more complex laboratory tests of blood and other tissues. In oncology, a biomarker may be a molecule secreted by a tumor or a specific response of the of the body to the presence of cancer. It can help in identifying early-stage cancers, forecasting how aggressive a cancer might be, or predicting how well a patient will respond to treatment.

Some examples of biomarkers used for screening for the presence of cancer or assessing the effectiveness of treatment are AFP (liver cancer), BCR-ABL (chronic myeloid leukemia), CA-125 (ovarian cancer), CA19.9 (pancreatic cancer) and CEA (colorectal cancer).

Biomarkers are also used to predict or monitor cancer recurrence. For example, the Oncotype DX® breast cancer assay is used to predict the likelihood of breast cancer recurrence in women treated for early breast cancer. Oncotype DX looks at a panel of 21 genes in cells taken during tumor biopsy and gives a recurrence risk score.

Cancer biomarkers have also shown utility in monitoring how well a treatment is working over time. Researchers continue to explore the potential of these biomarkers as alternatives to current image-based tests, such as CT scans and MRIs.

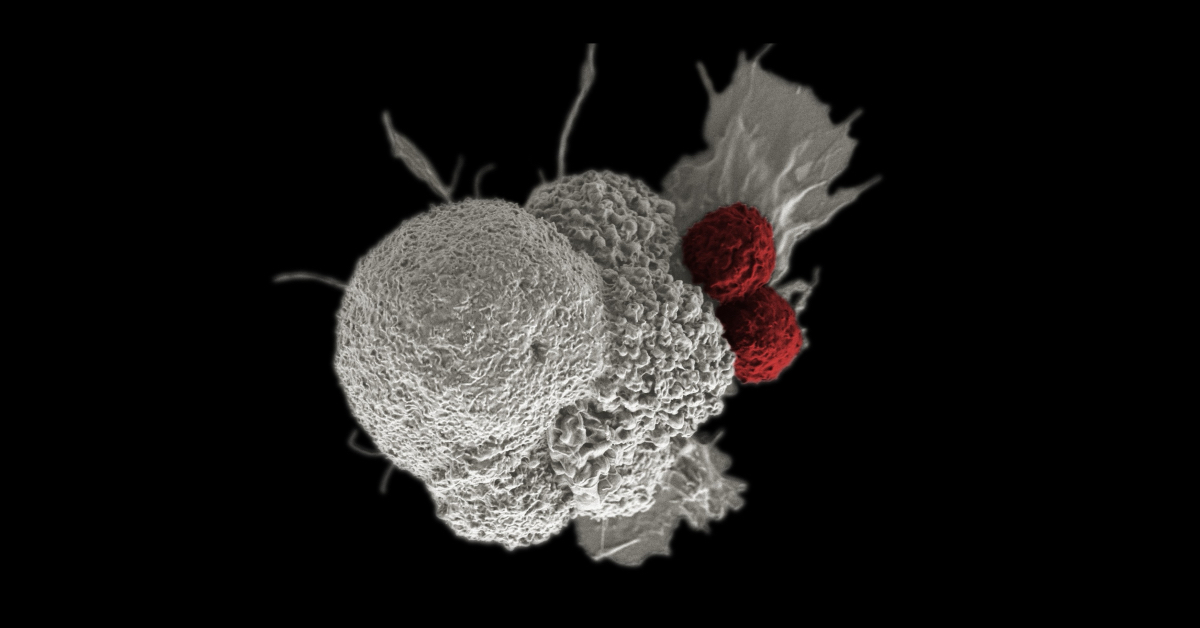

One of the hottest areas of biomarker research is in immunotherapy, a type of treatment that manipulates a patient’s immune system to fight cancer with drugs or modified immune T cells. In the past several years, immunotherapy has had dramatic success in some patients with some types of cancer, but only a minority of patients currently respond to treatment with immunotherapy agents as of right now.

Researchers are working hard to discover biomarkers that could identify, in advance, which patients are likely to respond to immunotherapy. In some types of cancer, the presence or absence of immune “checkpoint” molecules such as PD1 on immune cells or PDL-1 in cancer cells has been associated with a better or worse response to immunotherapy. For example, one clinical trial showed that the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab lowered the risk of death in patients with non-small cell lung cancer – and whose tumors expressed high levels of PDL-1—by 37 percent compared to chemotherapy.

Because the need for immunotherapy biomarkers is so important, the National Cancer Institute has funded a network of research centers and a data center to develop biomarkers for immunotherapy. The network consists of four Cancer Immune Monitoring and Analysis Centers (CIMACs)—one of which is at Dana-Farber—and a data storage center, the Cancer Immunologic Data Commons (CIDC), which is also at Dana-Farber.

Very informative and easy to follow. Would want to hear more information on this topic .