For Duane Witter, the most difficult part of his cancer treatment was recovering from his stem cell transplant and having to step away from teaching and coaching high school basketball in Farmington, CT.

“Before all this, I used to say that my superpower was to never miss a day of school,” he says. “Stepping away from that was so difficult.”

Witter’s acute myeloma leukemia (AML) diagnosis came at the end of the 2019 school year and right after his team had won the state championship. He received chemo treatment locally and was in remission for several months, during which he was able to return to coaching for a while.

Unfortunately, Witter’s disease recurred in 2020 — a development that would lead him to Dana-Farber and ultimately back to the court, even during COVID-19.

“I was prepared for this scenario by my local team,” he says. “They told me if my disease recurred that I would be referred out to a bigger hospital for a transplant, and to me Dana-Farber was a no brainer.”

A son turns donor

Witter’s Dana-Farber physicians, Mahasweta Gooptu, MD, and Marlise Luskin, MD, knew that the surest way to eradicate his disease was to get him a stem cell transplant.

“We think of AML as a blood cancer, but really it’s a malignancy of your stem cells,” Gooptu explains. “Basically, when these stem cells acquire certain genetic changes, instead of producing normal cells, your body begins to produce abnormal cells. We call these blasts.”

For some patients with “good risk” disease, chemotherapy alone can be enough to induce remission, especially in young patients like Witter.

“But, unfortunately in the majority of cases chemotherapy alone is insufficient,” Gooptu says.

To attain remission, allogenic stem cell transplantation after chemotherapy is required to essentially replace the cells that produce normal-functioning blood cells. The aim is to completely eradicate any cancerous cells left behind after chemotherapy.

Typically, physicians look for a complete genetic match for transplant, but one was not found for Witter in the stem cell donor registry. Gooptu and the Dana-Farber team knew this was a possibility and were prepared to perform the transplant with a donor that was a 50% match, also known as a haploidentical transplant. This meant that Witter’s son, Trey Witter, was an eligible donor.

“Thanks to research in the field of haploidentical transplants over the last decade, the outcomes from these transplants have dramatically improved and truly expanded donor options for patients like Duane who do not have a full match and do not have the time to wait either,” says Gooptu.

Gooptu and others led a recent study on the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research registry, which showed that survival outcomes can be similar for patients receiving haploidentical transplants and fully matched donor transplants when high-intensity, or myeloablative, chemotherapy is used.

Trey Witter is following in his father’s footsteps and studying physical education. He was thrilled to have the opportunity to help his father.

“That is a special thing that we share,” says the elder Witter. “I’m tremendously proud of both of my sons.”

The long and hard work of recovery

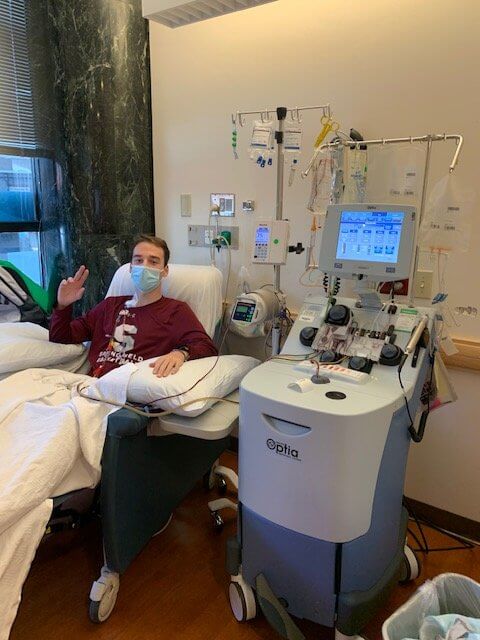

The transplant went well, with minimal complications, but Witter’s long recovery would prove challenging.

“The recovery process after a stem cell transplant is often overlooked,” says his nurse practitioner Bonnie Dirr, NP. “Having an exceptionally active individual like Duane put into a feeble state can have a lot of consequences not only physically, but also mentally.”

Dirr and Gooptu noticed that Witter was becoming withdrawn as his recovery dragged on. So Dirr worked with him to come up with a plan that would help him regain his emotional and physical strength while staying within his post-transplant restrictions.

“My job as nurse practitioner isn’t just about medical management,” she says. “It’s also about supporting my patients emotionally and mentally; it’s about making sure they can get back to work safely; it’s about working with them to make sure they can return to a normal life or to find a new normal.”

Part of that process would be physical therapy, thought Gooptu and Dirr, and they tried to refer Witter to a clinic.

“As a physical education teacher, I thought I knew it all,” Witter laughs. “So, I was having none of it at first.”

But eventually he chose to give it a shot and found that it accelerated his recovery.

“That was immensely helpful, and I’m grateful for the team for encouraging me into it. It’s why I was able to return to coaching sooner than expected,” says Witter.

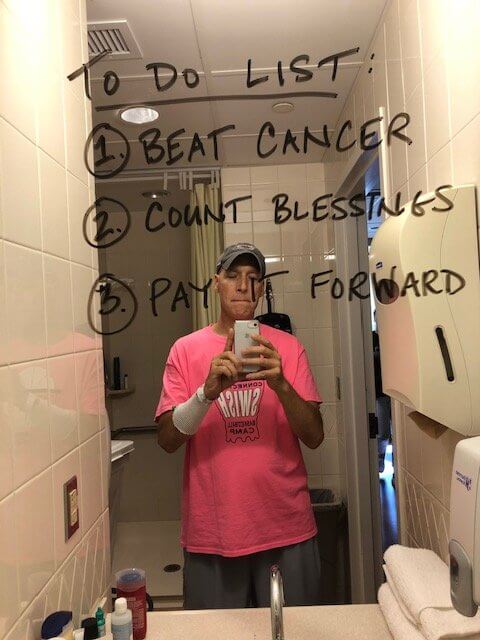

Witter worked hard at recovery. Along with physical therapy, he reminded himself of his three goals every day. The first was to get to the other side of cancer treatment.

“The nurses at Dana-Farber were unbelievably helpful through this. They always had amazing advice for me,” he says.

The second, a reminder to count his blessings even while he was so weak that he couldn’t get up to fetch the newspaper.

“Every day I reminded myself to appreciate the things that I had in my life — which was a lot,” he says. “My wife was my greatest supporter. She was there every step of the way. Her and my sons, my family, that’s who I play for. That’s who I wanted to get well for.”

Witter’s community came out to support him as well. Together they raised over $19,000 to help Witter and his family through this incredibly difficult period.

His final goal was to pay everything that he had earned forward.

“I’d like to do anything possible to help now that I’ve gone through all of this,” Witter says. “I have a new perspective. It’s like when I talk to my players about injuries. When you’re injured, you get basketball taken away from you, and when you return you appreciate it more. I think I’m appreciating life more now that I’m getting another chance.”

Returning to coaching with a new perspective

Motivated by his family, his students, and his team, Witter powered through recovery until he felt well enough to return to what he loved doing the most. He would hit another roadblock before the school year began, but his care team helped him through it.

Witter’s immune system was still recovering, and since the transplant had essentially reset it, he had to get many of the vaccinations he received as a child again. Returning to school normally would have been too dangerous for him in his immunocompromised state.

But Witter was determined. So, with direction from Dirr and Gooptu, Witter ran his gym classes outside on the school’s field where he was at a low risk of being exposed to viruses.

Now, fully recovered, Witter has been able to return to what he loves most: coaching his basketball team and teaching physical fitness courses.

“We lost our first game this year, but now I appreciate that there is a richness in that loss,” he says. “I was able to just enjoy the night. I’d rather be able to coach and lose every game than not be able to coach.”

Just like Witter, though, the team has bounced back and have won their last five games.

My husband too had the benefit of being cared for & shepherded by Bonnie Dirr. She, along with Dr. Corey Cutler, have at this point given us 7 1/2 years together that we would not have had. Other will always be our hero’s.