CAR T cells’ superpower is to identify cancer-related targets on the surface of tumor cells and order an attack on those cells. But they lack anything resembling X-ray vision to detect nefarious protein targets within tumor cells.

That shortfall has limited their effectiveness in diseases like acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), in which tumor cells display few surface targets, called antigens, associated with cancer. Now, however, Dana-Farber scientists have developed an alternative that uses the special skills of T cells’ compatriots in the immune system — natural killer, or NK, cells.

Like CAR T cells themselves, which are endowed in a lab with a receptor for latching onto certain kinds of cells, the NK cells at the heart of the new approach are not ordinary NK cells, but ones engineered for a specific mission. By undergoing a series of chemical and genetic alterations, they not only persist longer and proliferate more profusely than typical NK cells but are also armed with a receptor for bits of an abnormal protein produced inside certain AML cells.

In a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers report that the highly weaponized cells staged a potent attack on lab-grown AML cells carrying the protein, while leaving other cells largely unharmed. In animal models of the disease, the enhanced NK cells significantly improved outcomes compared to other treatments. The results have encouraged researchers to plan clinical trials of the therapy.

“NK cells have many of the attributes of an effective cancer therapy,” says Rizwan Romee, MD, who led the study with Dana-Farber President and CEO Laurie H. Glimcher, MD, Han Dong, PhD, of the Glimcher laboratory, and Jianzhu Chen, PhD, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “They’re ‘born to kill,’ and are less likely to produce certain complications than some other approaches. By modifying them to enhance their capabilities, we’re hoping they can become an even more effective cancer therapy.”

Overcoming obstacles

For all their inherent advantages as a potential cancer therapy, NK cells also have several shortcomings. They proliferate modestly, have relatively brief lifespans, and don’t specifically target cancer cells. Romee and other scientists have met the first two challenges by developing “memory-like” NK cells. Made by exposing NK cells to immune-signaling substances called cytokines, memory-like (or ML) NK cells live longer, grow and divide more robustly, and are active against leukemia. In a phase 1 clinical trial, ML NK cells produced beneficial responses in more than half of patients with relapsed AML with no apparent harmful side effects.

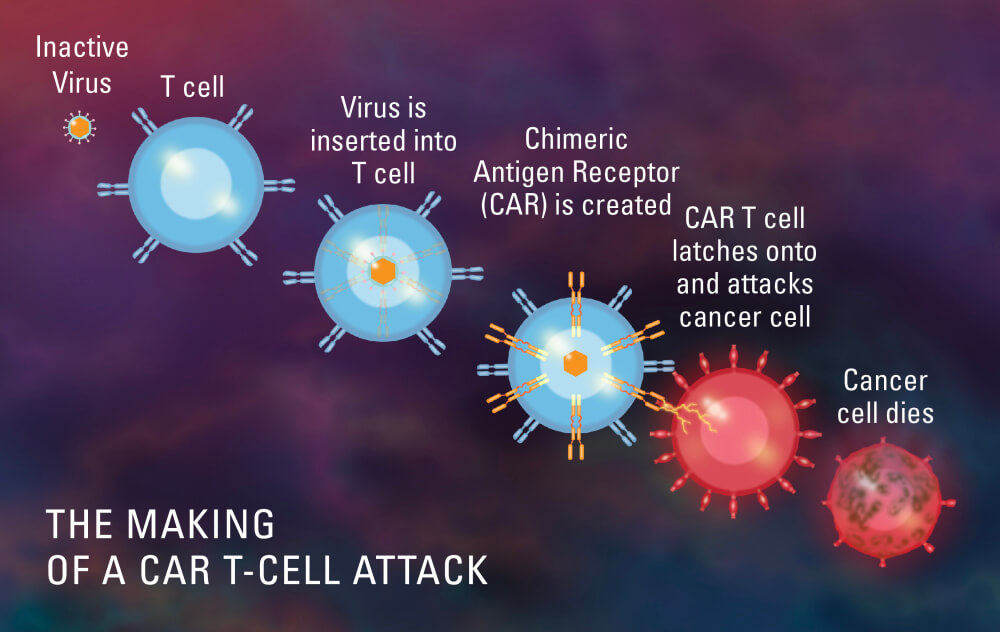

To improve NK cells’ ability to recognize and kill cancer cells, Romee, Glimcher, and their team took a page from the creation of CAR T-cell therapies — and revised it. CAR T cells are made by collecting thousands of a patient’s immune system T cells and equipping them with extra genes. The genes cause the cells to deck themselves in special receptors, called CARs (chimeric antigen receptors), that lock onto antigens on B cells — white blood cells that are cancerous in multiple myeloma and some lymphomas — and incite an immune attack on them.

While CAR T cells are adept at spotting certain antigens on the surface of cells, they’re blind to malevolent proteins within cancer cells. There is, however, an alternative that helps immune system cells spy on the tumor cell interior.

Mutations in genes can cause cells to produce abnormal, dysfunctional proteins. Chunks of these proteins, called neoepitopes, can be lifted to the surface of a cell and displayed there in brackets known as HLA molecules. T cell receptors, or TCRs, enfold these peptides and, recognizing them as a sign of cancer, trigger the immune response.

One of the obstacles to targeting AML with CARs is the scarcity of cancer-signaling antigens on the surface of AML cells. But evidence of their cancerous nature can sometimes be found cupped inside the cells’ HLA molecules.

One of the most common genetic mutations in AML, present in about 30% of all adult cases of the disease, causes tumor cells to produce an abnormal version of a protein called NPM1c. A neoepitope of that protein is shipped to HLA molecules on the cells’ surface, where it comes under the watchful eye of the immune system.

For the current study, researchers equipped ML NK cells with a novel creation: a “TCR-like CAR,” a hybrid of the two kinds of receptors. Although it is technically a CAR, it works like a TCR in that it can detect the NPM1c neoepitope nested in HLA molecules. They then tested their creation in laboratory samples of AML cells carrying the abnormal NPM1c protein. In these experiments and studies in animal models of human AML, the newly empowered NK cells mounted a powerful, pinpoint attack on the tumor cells.

“Our results demonstrate that ML NK cells with an innovative CAR can be developed as an efficient immunotherapy for this molecular subtype of AML,” Glimcher says. “They also provide a new approach to using ML NK cells as an attractive platform for engineering novel CAR proteins in the future.”