Tom Lomaglio, Jr., learned he had a rare blood cancer called Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia (WM) in 2000. His father, Tom, Sr., had been diagnosed in 2004, and then his sister, Diane, in 2007.

They were all referred to Dana-Farber for care. When Lomaglio visited the first time, he met Steven Treon, MD, PhD, director of the Bing Center for Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia. At that time, Treon was the solo practitioner in the Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia program he’d created at Dana-Farber in 1999. That program became the Bing Center in 2005.

“Dr. Treon was by himself, seeing patients. I was pretty much there from the beginning,” Lomaglio says.

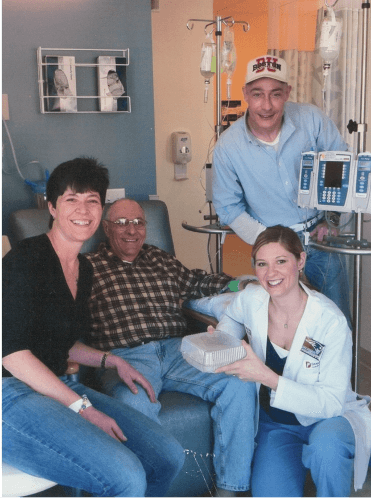

Since then, the Lomaglio family has come to see Dana-Farber as a second home. Not only have they received care that has extended their lives, but they have also been a part of the Bing Center from its inception. The Bing Center endeavors to find treatments for this disease and to understand its roots — particularly in families like Lomaglio’s. The family’s participation — in clinical research, patient-physician summits, clinical trials, and more — has resulted in the development of close lifelong relationships with their doctors.

“We take care of these families,” says Treon. “We act like a family practice.”

Creating a full life with a rare cancer

Lomaglio, who is now 60, was 38 and working at Boston University toward a doctoral degree in geography when he started to feel run down. He visited multiple doctors in his community west of Boston, MA, before hearing the diagnosis of Waldenström’s.

WM is a rare form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The disease starts in the bone marrow, where white blood cells called B cells become malignant. They circulate in the blood and create too much of a protein called immunoglobulin M (IgM). This protein normally helps fight infections, but in excess it thickens the blood, making it hard to flow through vessels.

“It’s a devastating diagnosis,” says Lomaglio, who with his doctor’s encouragement made an appointment at Dana-Farber. “Dr. Treon told me he’d devoted his life to ridding the world of this disease. That’s what I needed to hear.”

Lomaglio hoped to finish his degree, but it would not be so. Just a few years later, his father, who is now 85 years old, also started feeling run down. His doctor diagnosed him with WM, and his son connected him to Dana-Farber.

“I’m sort of the logistics guy,” says Lomaglio. “I knew who everyone needed to see at Dana-Farber.”

When Lomaglio’s sister Diane started having abdominal pain, she learned she also had WM. About one percent of Waldenström’s cases are familial, even though the disease is one that occurs when certain genes spontaneously mutate during adulthood. Soon, the entire family was traveling into Boston frequently for treatments. They’d go in together and sometimes even receive infusions at the same time.

“I’m not living the life I’d expected,” Lomaglio says. “But I’ve kept my family alive as long as possible, and that’s an accomplishment.”

Watch. Wait. Educate.

One of Treon’s approaches to care was to set up patient-physician summits at the Bing Center to help everyone learn more about treatments.

“It’s a brilliant approach,” says Lomaglio. “Together, educated doctors and patients make better decisions.”

This approach is particularly important in a disease like Waldenström’s, which does not always require treatment immediately. Lomaglio, for example, has spent most of the past few decades watching and waiting. When the disease begins to overtake the bone marrow, it’s time to treat.

He received treatment just three times over the first twenty years. In 2020, he tried a therapy called BDR — bortezomib, dexamethasone, and rituximab — that he’d been tracking for over a decade.

Lomaglio had first heard hints of a promising experimental drug during one of Treon’s early patient-physician summits. That drug later became bortezomib (Velcade), the first proteasome inhibitor, which was approved for treatment of multiple myeloma in 2003. Treon had begun investigating it to treat Waldenström’s a few years later.

“I watched this drug go from development to use and then finally it was pushed into me,” says Lomaglio, whose primary oncologist is now Jorge J. Castillo, MD, clinical director at the Bing Center. He responded so well to the treatment that his IgM blood counts fell into the normal range.

Managing the unexpected

Lomaglio and his father are currently watching, waiting, and managing their symptoms. Their experience differs from that of Lomaglio’s sister, who had a more aggressive form of the disease.

At the time of diagnosis, Diane had a mass of Waldenström cells in her abdomen. She needed treatment right away, so Lomaglio got her connected to Dana-Farber.

Later, her red blood cell counts dropped often and without warning, putting her at risk of organ damage as tissues become starved of oxygen. She did join a few clinical trials and ultimately ended up having a stem cell transplant. But graft-versus-host disease, in which the transplanted immune cells attack the recipient’s healthy organs, and a later bout with influenza caused lung damage. She passed away in 2021 at age 58.

“I’m still so heartbroken,” says Lomaglio. “But we wouldn’t have had so much time with her without the wonderful people at Dana-Farber.”

Lomaglio is grateful to have found a home-away-from-home for his family at Dana-Farber, not only for the care received but also for the sense of hope that keeps him going. Because of the value his doctors have put on education and communication, Lomaglio is confident that he and his family are doing the right thing, working with the right experts, and living the best life they can under the circumstances.

Recently, Treon and colleagues have also created a research endeavor called the 300 Project. They are working with about 300 families who, like Lomaglio, have multiple family members with WM or another blood cancer. Over the past 15 years, they’ve collected data and samples for study, and they now are applying multidisciplinary research to understand the roots of familial WM.

“I know I’m in the perfect place to try something on the cutting-edge when I need it,” says Lomaglio. “Until then, I’m doing what I can to stay strong mentally and physically against this disease.”