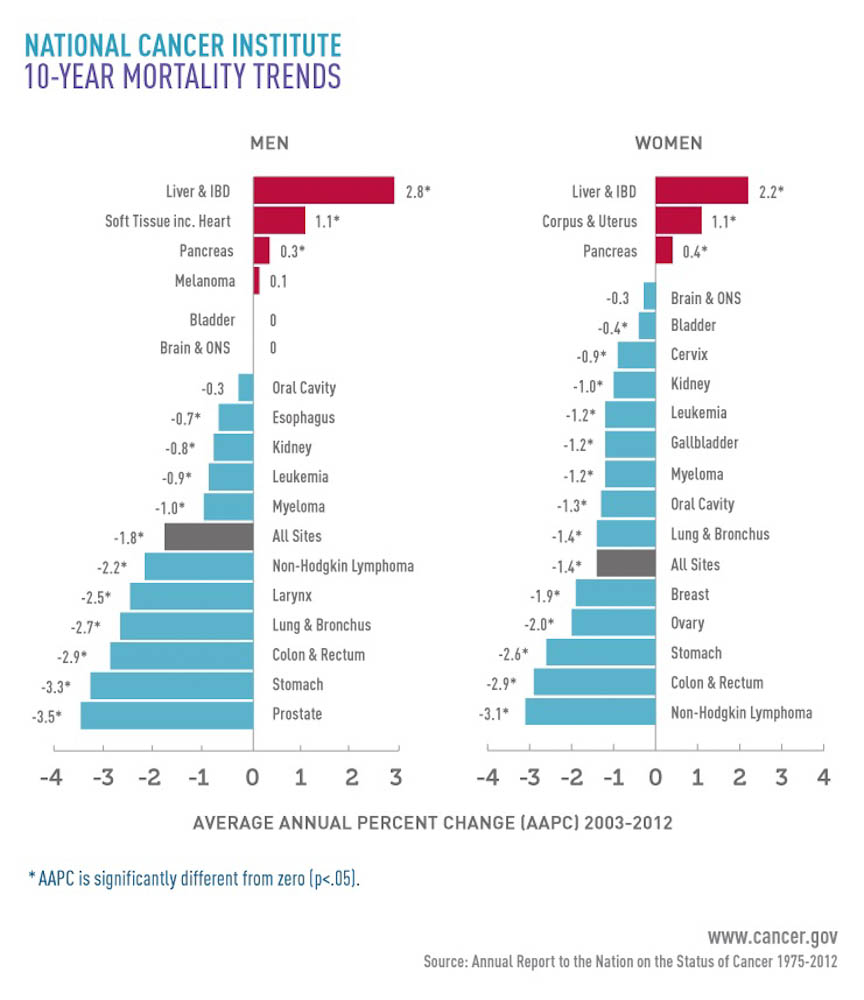

There was mostly good news in the most recent annual government report on cancer trends in the United States: Overall death rates, which have been dropping since the early 1990s, continued to decline between 2003 and 2012.

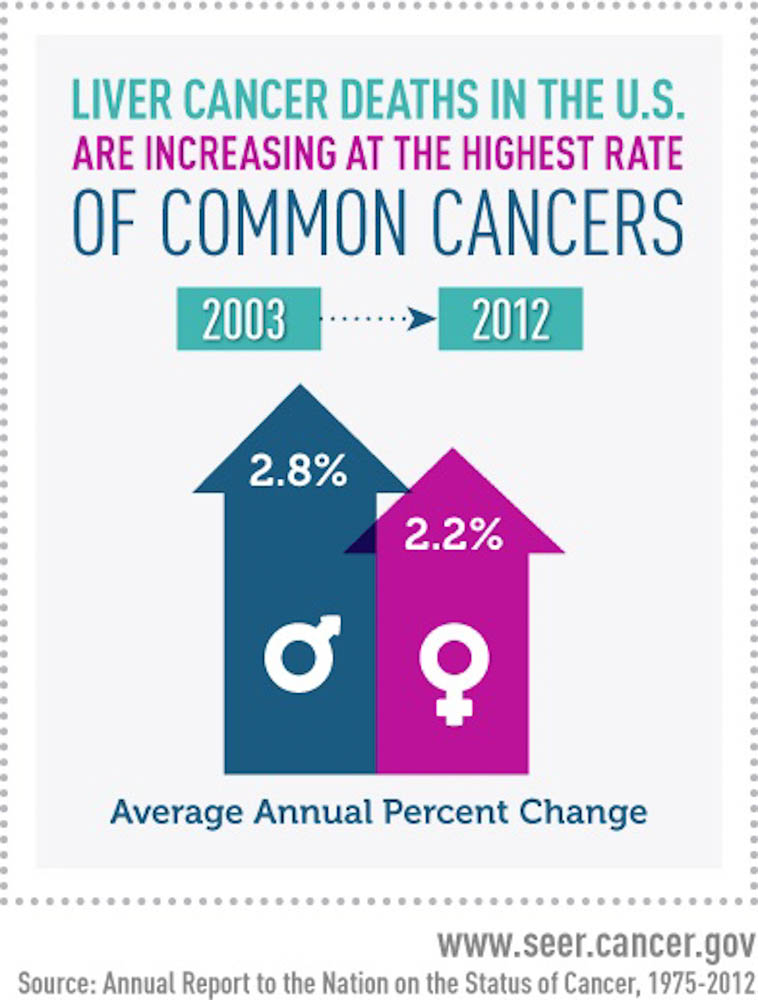

But the report focused on a disturbing exception: The death rate for liver cancer during that same period increased by 2.7 percent per year, maintaining an upward rise since the 1980s.

Primary liver cancer – that which develops in the liver as opposed to metastasis from another organ – is projected to be diagnosed in 39,230 individuals this year, and 27,170 deaths are expected from the disease, which typically isn’t detected until it is in advanced stages. The cancer affects twice as many men as women.

The rise is steepest in a particular population – baby boomers born between 1945 and 1965. From 2008 to 2012, deaths caused by liver cancer increased 3.5 percent per year among those 50 and older, but decreased 3.9 percent per year among adults younger than 50 years of age.

These disparities are related to an important risk factor for liver cancer – infection with the hepatitis C virus, HCV. (Other risk factors include infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), cirrhosis, heavy alcohol use, obesity, diabetes, and smoking.) Although an HBV vaccine has been available since 1982, there is no preventive vaccine for HCV.

Read more:

Hepatitis C virus infection was at its highest levels during the 1960s to 1980s, before the virus was discovered and found to be transmitted through contaminated blood transfusions and use of injected drugs. Since then, HCV screening has reduced infections and if diagnosed, it can be treated with antiviral drugs, reducing the risk of liver cancer.

Federal guidelines say people at high risk for HCV infection should be screened, and in 2012 a recommendation was issued for one-time HCV screening of adults born between 1945 and 1965. A 2013 study, however, found that only 12.3 percent of baby boomers reported having had the test. “Most patients only get a diagnosis of HCV infection when they present with some symptom of active or chronic liver disease,” according to Anuj Patel, MD, a medical oncologist in Dana-Farber’s Center for Gastrointestinal Cancer.

Emphasizing the importance of HCV screening, Patel said that early identification allows for early treatment of HCV infection, noting that five different combinations of oral drugs approved since 2013 are highly effective and well-tolerated. Early identification also allows for early detection of complications of chronic HCV infection, including liver cancer, and these measures have been found to improve outcomes and survival.

HCV infection is responsible for about 20 percent of liver cancers, and eventually the epidemic will wane as a result of demographic factors, screening and treatment. Still, some mathematical models predict that incidence of liver cancer will continue to climb for several decades; in addition to the virus, risk factors like obesity, fatty liver disease, and diabetes are becoming more prevalent.

“The growing burden of liver cancer is troublesome,” said Tom Frieden, MD, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a statement when the report was released. “We need to do more work promoting hepatitis, treatment, and vaccination.”