Medically reviewed by Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, MD, MPH

Colorectal cancer forms in the tissues of the colon or rectum, which make up the large intestine. The colon and rectum are part of the body’s digestive system, which is made up of the esophagus, stomach, and the small and large intestines. The first six feet of the large intestine are called the colon. The remaining several inches of the large intestine form the rectum.

While historically regarded as a disease only impacting older adults, since 1994 cases of young-onset colorectal cancer have increased by 51 percent, according to the National Cancer Institute. By the year 2030, colon cancer incidence is expected to double, and rectal cancer incidence is expected to quadruple in individuals under age 50. The Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center is among the first centers in the country dedicated to patients in this age group diagnosed with cancer of the colon or rectum.

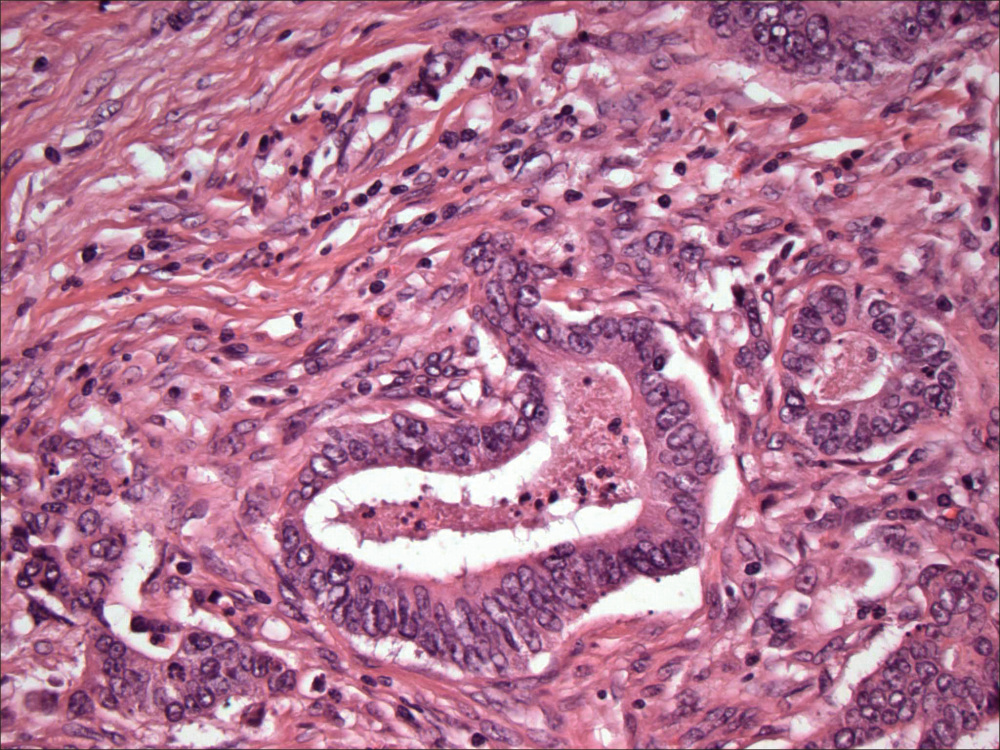

Different types of cancer can develop in the colon or rectum. Most colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas, which are cancers from glandular tissue. Other cancer types that can occur in the colon include carcinoid tumors, small cell carcinomas, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST).

Risk factors

As with many types of cancer, it’s important that colorectal cancer be diagnosed and treated early in its course of development. Anyone with symptoms of the disease that persist for more than a few weeks should schedule an appointment with their doctor. Risk factors for colorectal cancer include:

- Increasing age: Most people who develop colorectal cancer are 50 or older.

- A family history of cancer of the colon or rectum.

- Certain hereditary conditions, such as familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, called Lynch syndrome.

- A history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

- A personal history of cancer of the colon, rectum, ovary, endometrium, or breast.

- A personal or family history of adenomas (polyps) in the colon or rectum. These growths can be pre-cancerous. Most adenomas will not turn into cancer. However, regular screening to remove them reduces the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Environmental and lifestyle-related factors, such as lack of exercise, obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

- A diet high in red and processed meat.

- Low vitamin D levels.

Symptoms and signs

Potential symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer include:

- A change in bowel habits.

- Blood (either bright red or very dark) in the stool.

- Diarrhea, constipation, or feeling that the bowel does not empty all the way.

- Stools that are narrower than usual.

- Frequent gas pains, bloating, fullness, or cramps.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Feeling very tired.

- Vomiting.

- Anemia (low red blood cell count).

These symptoms and signs can have many causes and may not be due to cancer. It is important to discuss these symptoms or signs with your doctor.

Many people, particularly those with polyps or early stages of colorectal cancer, may not have any symptoms or show any signs, making the disease difficult to detect without regular screening. Screening often makes it possible to find cancers before symptoms appear.

Screening and prevention

There are several ways to screen for colorectal cancer. Most people have heard of colonoscopy, in which a doctor views the interior of the colon using a tiny camera attached to a flexible tube. But there are other techniques as well. Deciding which one is right for you depends on a variety of factors, and you should discuss them with your doctor or care provider.

Options for screening include:

- Fecal occult blood testing: A test to check stool (solid waste) for blood that can be seen only with a microscope. Small samples of stool are placed on special cards and returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing.

- Sigmoidoscopy: A procedure to look inside the rectum and sigmoid (lower) colon for polyps (small areas of bulging tissue), other abnormal areas, or cancer. A sigmoidoscope is inserted through the rectum into the sigmoid colon. A sigmoidoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It also has a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Colonoscopy: A procedure to look inside the rectum and entire colon for polyps, abnormal areas, or cancer. A colonoscope is inserted through the rectum into the colon. A colonoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It will also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Virtual colonoscopy: A procedure that uses a series of X-rays called computed tomography (CT) to make a series of pictures of the colon. A computer puts the pictures together to create detailed images that may show polyps and anything else that seems unusual on the inside surface of the colon. This test is also called colonography, or CT colonography.

- DNA test: A test of the stool for small pieces of DNA that come from cells lining the colon and rectum. It looks for abnormal DNA that may be due to a cancer.

- Double-contrast barium enema: A series of X-rays of the lower gastrointestinal tract. A liquid that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound) is put into the rectum. The barium coats the lower gastrointestinal tract and X-rays are taken. This procedure is also called a lower GI series. It is rarely used anymore.

Diagnosis and tests performed if disease is suspected

History and physical exam: Taking a thorough medical history is important to help make a treatment plan appropriate for your body and your goals. Your health care provider examines your body to check general signs of health, including signs of disease, such as lumps and swollen lymph nodes.

Blood chemistry studies: Your doctor takes a blood sample to check the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body.

Complete blood count (CBC): Your doctor takes a blood sample to check the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay: A test that measures the level of CEA in the blood. CEA is released into the bloodstream from both cancer cells and normal cells. CEA is not a screening test, but when someone is diagnosed with colorectal cancer, it is helpful to follow how the cancer is doing and how a patient’s treatment is progressing.

Biopsy: If you were diagnosed by a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, a biopsy was likely already taken and sent to pathology to look at the cells under a microscope. However, after diagnosis, other biopsies may be needed if abnormalities are found elsewhere in order to determine the right amount.

Radiology exam: Common radiology procedures include:

- Chest X-ray: An X-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An X-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an X-ray machine.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed images of areas inside the body.

- PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radionuclide glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the image because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells. OET scans are sometimes helpful in the workup for colorectal cancer but are not routinely needed in every patient.

Treatments for colorectal cancer

There are several types of treatments, from standard therapies to those being tested in clinical trials. Standard treatments include:

Surgery

Surgery (removing the cancerous growth in an operation) is usually the key component of treatment for most patients with colorectal cancer.

Advances in understanding colorectal cancer, such as making sure enough lymph nodes are removed during the operation, have made surgery more likely to be successful.

A surgeon may remove the cancerous growths through:

- Local excision: If the cancer is found at a very early stage, the surgeon may remove it without cutting through the abdominal wall. The surgeon may put a tube through the rectum into the colon to cut the cancer out. This is called a local excision. If the cancer is in a polyp, the operation is called a polypectomy.

- Resection of the colon or rectum with anastomosis: Part of the colon or rectum containing the cancer and nearby healthy tissue is removed, and then the cut ends of the colon are joined.

- Resection of the colon or rectum with colostomy: If the doctor is not able to sew the two ends of the colon or rectum back together, an opening is made on the outside of the body for waste to pass through. This is called a colostomy.

For patients whose cancer has metastasized, or spread beyond the colon or rectum, doctors may recommend surgery or other options including:

- Radiofrequency ablation: Radiofrequency ablation uses a special probe with tiny electrodes to eliminate cancer cells. Sometimes the probe is inserted directly through the skin and only local anesthesia is needed. In other cases, the probe is inserted through an incision in the abdomen.

- Cryosurgery: Cryosurgery is a treatment that uses an instrument to freeze and destroy abnormal tissue. This type of treatment is also called cryotherapy.

Chemotherapy

For some patients, chemotherapy may be recommended. Chemotherapy, along with radiation therapy, is used to eliminate cancer cells that remain in the body after surgery. The aim of these treatments is to lower the risk that the cancer will come back. They are called adjuvant therapy.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells without harming normal cells.

Some targeted therapies used in colorectal cancer focus on certain changes that occur around tumors, specifically the blood supply that feeds the tumor. These drugs are called angiogenesis inhibitors, and they stop the growth of new blood vessels that tumors need to grow and spread.

Another kind of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer blocks a protein on cancer cells called the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which drives the cells to divide and spread.

More and more, targeted therapies focus on specific molecular changes in a patient’s individual tumor. Patients may be offered testing of their tumor for genetic mutations. This may help guide care using standard treatment and also direct patients to the right clinical trial to find better therapies for attacking their tumor.

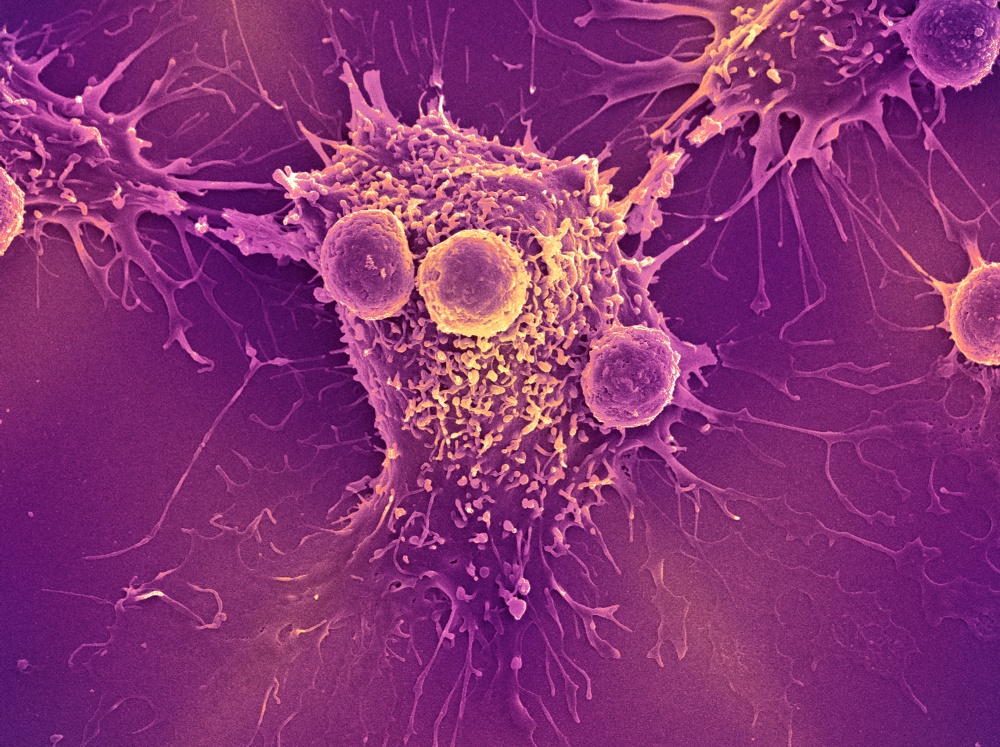

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a kind of treatment designed to try to help your body’s immune system better fight the cancer. It is a rapidly emerging field and strategy of treating certain cancer types, and an area of a lot of exciting research.

In colorectal cancer, the role of immunotherapy so far is limited to tumors that have a particular molecular feature called microsatellite instability. This is a small percentage of patients with advanced colorectal cancer, and research is being conducted to figure out how to use immunotherapy in patients who don’t have microsatellite unstable tumors.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy X-rays to eliminate cancer cells or keep them from growing.

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

While radiation therapy is not as commonly used in colorectal cancer as in other cancer types, there are times when radiation therapy is recommended:

- After surgery and chemotherapy to further decrease the chance of the cancer returning.

- To reduce the tumor prior to surgical resection.

- To help control cancers that cannot be removed surgically.

- To help symptoms from specific metastases, to reduce pain in that area.

However, radiation is considered if the cancer is in the rectum. It will sometimes be offered prior to surgery and given along with chemotherapy as part of a preoperative treatment for rectal cancer.

Clinical trials

Promising new treatments for colorectal cancer are being tested in a variety of clinical trials. Here is a list of colorectal cancer clinical trials currently under way at Dana-Farber.

Tips for coping with colorectal cancer treatment

Not all patients with colorectal cancer experience side effects of treatment, and when such effects do occur, they’re often mild. Here are a few of the most common side effects of colorectal cancer treatments:

Gastrointestinal problems

Gastrointestinal disorders, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, can be side effects of both chemotherapy and pain medications. Such problems often can be alleviated with medications. For patients experiencing these problems, doctors recommend drinking plenty of fluids to avoid dehydration, and limiting caffeinated and sugary drinks.

Chemotherapy and pain medications also can also cause constipation. This can be eased by increasing fiber in one’s diet. Over-the-counter laxatives and stool softeners can also be helpful.

Pain

Pain may arise from the tumor itself or from treatment, such as surgery. As pain is easier to control when it’s mild, patients should tell their doctor as soon as they begin to have symptoms.

Hair loss

One of the most common side effects of chemotherapy, hair loss can be dealt with in a variety of ways. Some patients choose to shave their head before they begin to lose their hair; others opt to wear a wig or other head covering.

Neuropathy

Some chemotherapy agents can harm nerves, causing pain or numbness in certain areas. Sometimes, treatment adjustments can reduce this problem.

Research

Research in colorectal cancer is proceeding on several fronts. At Dana-Farber, scientists are exploring how genetic, behavioral, and environmental factors affect the disease’s development, progression, recurrence, and response to treatment. They’re investigating risk factors that may predispose some people to the disease and are studying the influence of diet and nutrition on disease development and recurrence.

A new center, called the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center, is also looking into the reasons for recent increases in colorectal cancer rates in young adults.

In clinical trials, investigators are also currently analyzing whether certain drug combinations work better in some patients than others, and why.

My wife is a survivor of Colo-rectal cancer 5 years ago. However, the ongoing effects of this have negatively affected her digestive and bathroom requirements. She suffers from SIBO and cannot find a good professional in this area to treat her.