Gene therapy and immunotherapy are both types of treatment for cancer and other diseases, and they have some points at which they intersect. But ultimately they represent different approaches to disease therapy.

Most diseases aren’t caused by a single mutant gene — an alteration in the DNA sequence — but some mainly rare, inherited disorders, may be due to mutation in a single gene. Gene therapy is a relatively new treatment method for patients with these rare genetic disorders that is largely still considered experimental. This type of therapy is designed to replace faulty genes in the body that are responsible for the disorder. For example, scientists might deliver copies of normal genes to the body to replace mutated genes that are causing cells to make an ineffective or dangerous protein. Some examples include severe combined immunodeficiency, sickle cell anemia and hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and rare inherited forms of blindness.

Alternatively, gene therapy may be used to inactivate or “knock out” a mutated gene that is functioning abnormally in an effort to reduce the gene’s harmful impact. Today, most gene therapy is performed in clinical trials, but it has been approved for one disorder in the United States and for two disorders in Europe. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 approved Luxturna, or voretigene neparvovec-rzyl, the first U.S. gene therapy product, for the treatment of an inherited form of vision loss that may lead to blindness.

Researchers are currently testing the effectiveness of gene therapy for several inherited disorders, such as severe combined immune deficiency, as well as blood diseases like sickle-cell anemia. Long-term studies are necessary to demonstrate that this approach is safe. Gene therapy clinical trials at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center include one for sickle cell disease and another for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency.

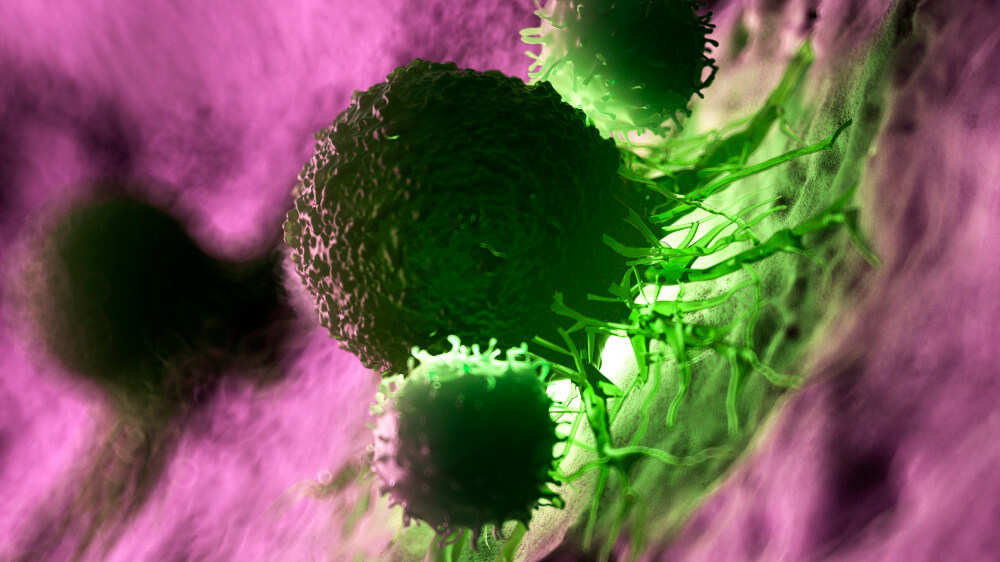

Immunotherapy, on the hand, is a strategy aimed at improving the ability of the body’s natural defenses’ — the immune system —- to recognize and attack cancer cells. Scientists have spent decades trying to understand why the immune system — particularly classes of specialized cells like T lymphocytes — sometimes fights cancer successfully, but more often fails to recognize tumor cells or fight them effectively.

Thanks to key discoveries in the 1990s, scientists learned how cancer cells can exploit naturally occurring molecules that turn off the body’s immune response to tumors. This led to insights about how to use drugs that can turn the immune response on again, harnessing its power to fight cancer.

Successes with this strategy have propelled immunotherapy to the forefront of cancer research and treatment, although this type of treatment only works in a minority of patients. In the past few years, several drugs known as checkpoint blockers have come into wide use, making a significant difference for many patients with melanoma, lung cancer, and other types of cancer.

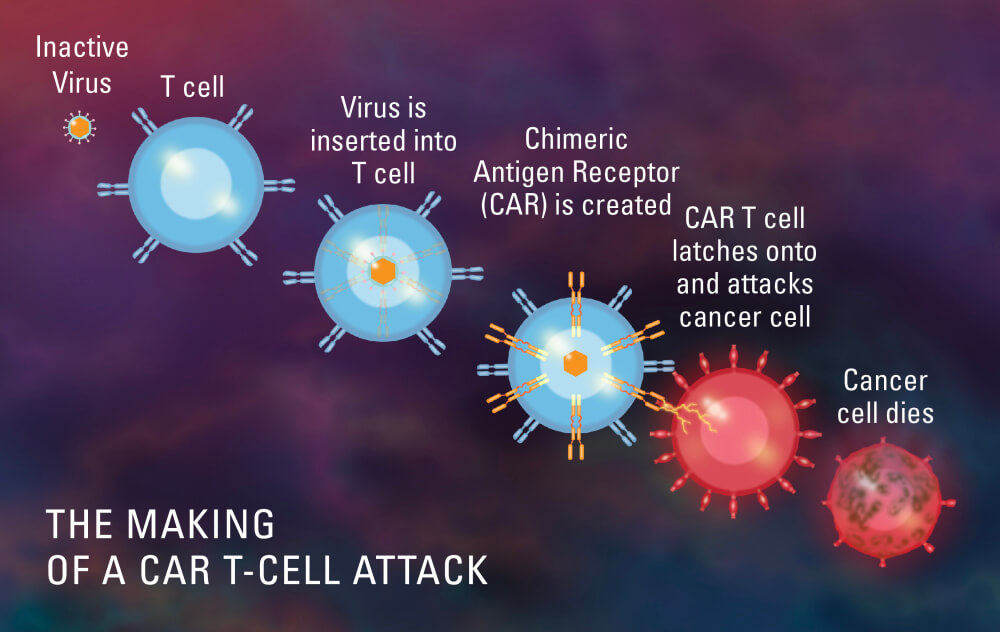

One form of immunotherapy makes use of genetically modified T cells: In other words, it uses gene therapy to perform immunotherapy. CAR-T cell therapy uses a patient’s own T cells, which are genetically modified in a laboratory to make a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). When the modified T cells are returned to the patient, the CAR enables the T cells to seek out and destroy the cancer cells wherever they are found in the body.

CAR T cells are considered gene therapy, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When the first CAR T-cell treatment, called tisagenlecleucel or Kymriah, was approved in August 2017 to treat a form of leukemia, the FDA called it the “first gene therapy” in the United States. “We’re entering a new frontier in medical innovation with the ability to reprogram a patient’s own cells to attack a deadly cancer,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said at the time.

Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center is a certified treatment center for Kymriah for patients up to age 25 and Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center is a certified treatment center for Kymriah for young adults ages 18 to 25.

What is going on with respect to Sarcoma research? It is so difficult to find out what is going on with respect to sarcomas.

Thank you for reading and apologies for the delay in response. Due to the high volume of comments we receive, we are usually unable to respond to each person individually. If you have a specific medical question related to this blog post, we would recommend talking to your doctor or other care provider. We’ve also gathered answers to some of the more frequent questions below:

-For more information on a particular type of cancer or the latest updates we have available, please visit our website (https://www.dana-farber.org/) or search our blog by clicking the magnifying glass at the top of our homepage: https://blog.dana-farber.org/insight/

-For information on whether you would be eligible for a certain treatment, please visit our website for more information on how to make an appointment or get an online second opinion: https://www.dana-farber.org/appointments-and-second-opinions/

-For information on clinical trials available at Dana-Farber and elsewhere, please visit the Dana-Farber database: https://www.dana-farber.org/research/clinical-trials/find-a-clinical-trial/. For clinical trials outside of Dana-Farber: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Wishing you all the best,

Dana-Farber Insight team