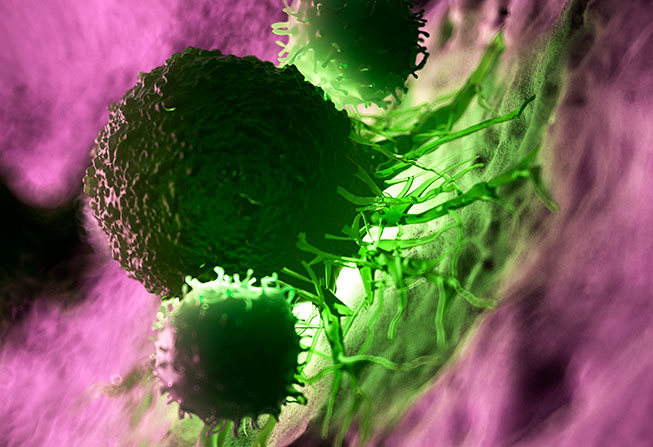

The immune cells known as natural killer (NK) cells are part of the body’s first line of defense against cancer. Many efforts are underway to harness NK cells as a form of cancer immunotherapy, but a critical question in the field remains: Why do some tumors tend to be sensitive to NK cells’ attacks while others are more resistant?

Now, an unprecedented study using more than 500 tumor cell lines led by Dana-Farber investigators has identified several genes and molecular mechanisms that determined the tumors’ responsiveness or resistance. It’s believed to be the most comprehensive, systematic assessment to date of tumor characteristics that predispose them to being killed by NK cells.

“We generated a useful map of the molecular events and features that make tumors more or less sensitive to NK cells,” says Constantine Mitsiades, MD, PhD, senior author of the report in Nature Genetics. Their findings identified some genes that had been suspected as playing a role in tumors’ responsiveness to NK cells, but implicated others that hadn’t been suspected or whose influence had been under-appreciated, Mitsiades notes.

These and other tumor characteristics identified in the study form a novel “landscape” of features influencing sensitivity to NK cells, the researchers say.

The investigators used two powerful, complementary platforms — one called PRISM and the other employing CRISPR gene editing — to simultaneously examine NK cell responsive to hundreds of “DNA-barcoded” solid tumor cell lines. There was no single, overriding feature of NK-sensitive tumors; however, the investigators say that those tumor cells tended to exhibit “mesenchymal-like” transcriptional programs; high transcriptional signatures for chromatin remodeling complexes, high levels of the B7-H6 gene, and low levels of HLA-E/antigen presentation genes.

Potential vulnerability

One potential benefit of research, Mitsiades says, is that the tumor features could be used as biomarkers to “provide insights into which patients may be more likely to benefit (or not) from each one of the diverse types of NK cell-based therapies that are currently been developed” and “may help inform current and future efforts to apply NK cell-based therapies for the treatment of human tumors.”

NK cells circulate in the bloodstream and act as sentinels, detecting infected and other abnormal cells and cancer cells and quickly going on the attack. However, they don’t persist for long periods in the circulation and it’s been shown that in cancer, NK cells are less abundant and subject to “exhaustion,” meaning they become less active against foreign or cancer cells. For use in cancer immunotherapy, NK cells can be harvested from donors and infused into patients; a major advantage of NK cell therapy over other immune cells is that they don’t cause graft-versus-host disease.

Most approved immunotherapies in use today focus on another immune cell type, T-lymphocytes or T cells, which also kill cancer cells, although they need to have antigens of cancer cells presented to them by other cells. But cancer is adept at suppressing the T cell response by activating immune checkpoints — such as PD-1 and PD-L1 — that keep T cells from recognizing and attacking cancer cells. Several drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors have proven very effective in certain cancers by releasing the checkpoint “brakes” on the T cell response.

However, some cancers are resistant to checkpoint blockade. In their new study, the researchers discovered that some tumors that generally are resistant to treatment with checkpoint blockers, such as many sarcomas, were sensitive to NK cells.

“One of the observations that came out of our study is that what makes a cancer cell resistant to a checkpoint inhibitor might make it more sensitive to NK cells,” says Mitsiades. This insight suggests that “molecular signatures of resistance to other forms of immunotherapy do not necessarily correlate with resistance to NK cells, and may even be associated with increased responsiveness to NK cells, providing a framework for using NK cell-based therapies and other immunotherapies sequentially.”