Key Takeaways:

- The goal of cancer vaccines is to spur the immune system against tumors.

- There is much promising research on vaccines designed to treat cancer, but currently they are almost all in the research and developmental stages.

- Some experimental treatment vaccines are “personalized” — created for each patient based on specific cancer-related proteins in the tumor caused by mutations.

Cancer vaccines are a form of immunotherapy aimed at enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack cancer cells, or to protect against certain forms of cancer caused by viruses.

Vaccine can help prevent some cancers

There are two approved preventive vaccines directed against cancer-causing viruses.

- A vaccine for hepatitis B, which can cause liver cancer. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends hepatitis B vaccine for all individuals age 0 to 18 years of age, and adults who are in risk groups for hepatitis B infection, such as health care of public safety workers who might be exposed to contaminated body fluids.

- A vaccine that protects against human papilloma virus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer in women, and can cause penis cancer in men and cancer of the anus and back of the throat in women and men. HPV vaccination is recommended for all children at age 11 or 12 years of age.

Vaccines against cancer-causing or other infectious microbes typically contain an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism — often a weakened or killed form of the microbe. The agent stimulates the body’s immune system to recognize the agent as dangerous and provides acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease.

Cancer treatment (or therapeutic) vaccines

Scientists believe it’s unlikely there will be a vaccine to directly prevent cancer in general because there are hundreds of different types of cancer — and most of them are not caused by viruses. Instead, researchers are working on an array of strategies to create treatment vaccines, also called therapeutic vaccines.

What are cancer treatment vaccines?

Treatment vaccines are designed to activate the immune response against cancer cells by targeting antigens — cancer-related proteins produced by tumor cells that aren’t present on normal cells or are present in lesser amounts in normal cells.

The body’s immune system has some ability to recognize and eliminate abnormal or malignant cells, but this mechanism doesn’t always work because cancer cells have various ways of escaping the immune response. The goal of cancer vaccine research is to devise ways of helping the immune system identify cancer cells and spurring a stronger response against them.

Few cancer vaccines have yet been approved for routine clinical applications. One cancer treatment vaccine, sipuleucel-T (Provenge), is approved to treat people with metastatic prostate cancer. It is made by removing immune cells from the patient’s blood and modifying them in the laboratory to target prostate cancer cells. They are then returned to the patient in an infusion to teach the immune system how to detect and destroy prostate cancer cells.

What’s the latest in cancer vaccine research?

A leading area of cancer vaccine research involves targeting “neoantigens” on cancer cells. These are antigens — distinctive proteins –—on the surface of cancer cells that are produced by mutations in the cancer cell’s DNA. Many neoantigens are specific to an individual patient’s cancer and aren’t found in normal cells.

“If we can identify neoantigens specific to a patient’s tumor, we can make a personalized vaccine to target those tumor-specific antigens,” says David Braun, MD, PhD, a Dana-Farber medical oncologist who is leading a trial of a neoantigen-based vaccine to treat kidney cancer (together with Toni Choueiri, MD).

Personalized vaccines

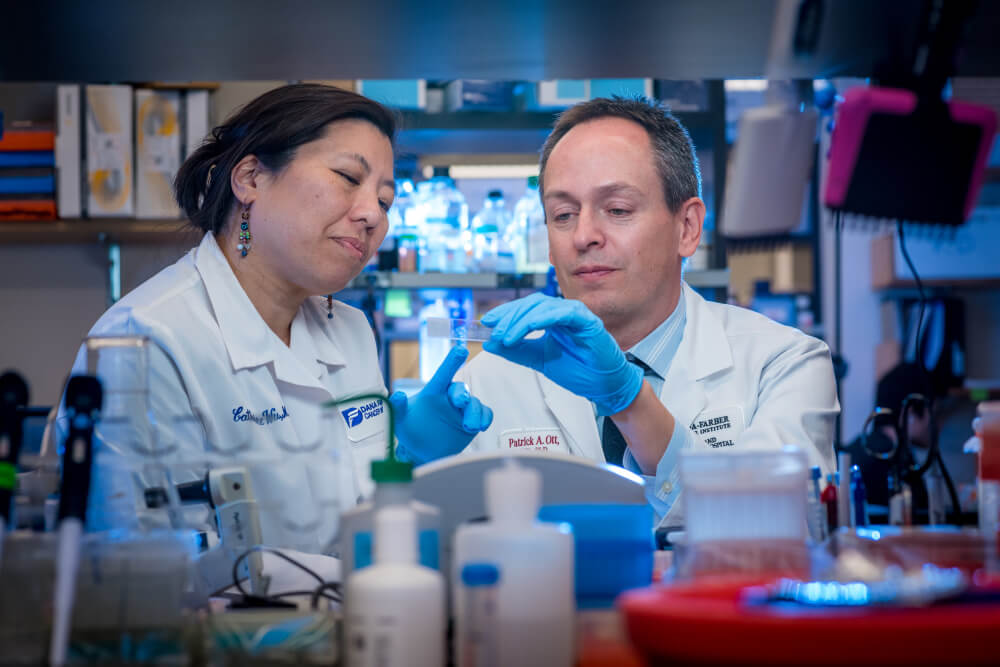

Researchers in Dana-Farber’s Center for Personal Cancer Vaccines are working to develop therapeutic vaccines tailored to each patient’s individual cancer. Led by Patrick Ott, MD, PhD, the scientists have developed a personal cancer vaccine, NeoVax, that is made by sequencing the genetic information of a patient’s tumor to identify neoantigens produced by mutations in that tumor. The vaccine is made by incorporating copies of as many as 20 neoantigens into the vaccine, which is given to the patient, along with a substance called an adjuvant to activate the immune response by killer T cells. The neoantigens are intended to steer the immune response to the site of the tumor.

In an encouraging report on eight melanoma patients treated with the NeoVax vaccine four years ago and a follow up study reported earlier this year, the immune response triggered by the vaccine induced strong immune responses which remained robust and effective in keeping cancer cells under control after several years, said Ott and study co-leader Catherine J. Wu, MD, of Dana-Farber, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Broad Institute. The patients had undergone surgery for advanced melanoma and were at high risk of a recurrence. After four years, all eight patients were alive, with six showing no signs of active disease. The researchers found that the immune cells activated by the vaccine “remembered” the neoantigens they had targeted and had even expanded their scope to recognize other melanoma antigens.

Besides melanoma, the vaccine is being tested in a number of different malignancies including kidney cancer, brain cancer (glioblastoma), ovarian cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma.

Other vaccine strategies involve targeting cancer-related antigens that aren’t specific to a particular patient.

Future challenges

While growing activity in cancer vaccine research is encouraging, challenges remain. Not all cancers may exhibit mutations creating enough neoantigens that can be exploited to make vaccines. Only tumors, with sufficient mutations, are good candidates for vaccines and other forms of immunotherapy.

Another challenge is that cells that make up tumors are heterogenous, so that neoantigens may be expressed only on some tumor cells and not others — and those may escape immunotherapy. In addition, cancer vaccines don’t work as well when there is a large amount of tumor; it’s likely that vaccines will be combined with other forms of treatment. Vaccines may also be combined with immune checkpoint blockers that release the molecular brakes that cancer cells use to dampen the immune response.

In spite of the challenges, scientists and biomedicine companies are optimistic about the future of cancer vaccines, as reflected in the hundreds of trials that are currently in progress.

It’s great to continue to learn of new cancer treatments. I hope new and better methods to fight against cancer continue.

É muito importante recebermos as newsletters do Dana Faber,porque os enfoques são autênticos e honestos de uma instituição como essa.

Exciting potential treatments! Thank you for your work and for sharing information. I have shared this newsletter with appropriate interested parties.

Question: my daughter refused to get the HPV vaccine, and although she does NOT have cervical cancer, there is evidence of the presence of the virus in her body, a tu or in her oral cavity which was removed. Is there anything she can do now to inactivate or discourage virus activity?

Hi Debra,

Thank you for reading! Unfortunately we can’t give specific medical advice over the Internet, but a medical professional should be able to address any questions you have.

Wishing you all the best,

DFCI